If a friend sent you to this page, they may be trying to tell you something. If you found it by yourself, consider that a point in your favor. This article appeared in This is True’s 23 January 2000 issue:

Even Your Best Friends Won’t Tell You

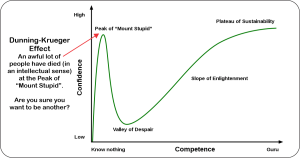

Sure there are a lot of incompetent people around. The problem is, they don’t know it, says Dr. David A. Dunning, a psychology professor at New York’s Cornell University, in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. He says that the reason they don’t know is that the skills people need to recognize incompetence are the same skills they need to be competent in the first place. Thus the incompetent often end up “grossly overestimating” their own competency, even when they’re making a mess of things. At the same time, very competent people tend to underestimate their abilities. Dunning notes such studies create a unique danger for the researchers. “I began to think that there were probably lots of things that I was bad at and I didn’t know it,” he said. (New York Times) …If you want to know what they are, just ask your wife.

The phenomenon is now better known as the Dunning-Kruger Effect (to provide credit to Dunning’s Cornell co-researcher, Justin Kruger), and Dr. Kruger is a Professor of Social Psychology at the New York University Stern School of Business.

In 2000, Dunning and Kruger “won” the Ig Nobel Prize in Psychology. In 2017, The Incompetence Opera premiered at the Ig Nobel Prize ceremony; it included “The Dunning-Kruger Song”.

Dunning is now a Professor of Psychology at the University of Michigan.

Inspiration

You might wonder what inspired Dr. Dunning to look into this and form his hypothesis in the first place. If you’re a True subscriber, you might guess something even more ubiquitous that Florida Man: stupid criminals.

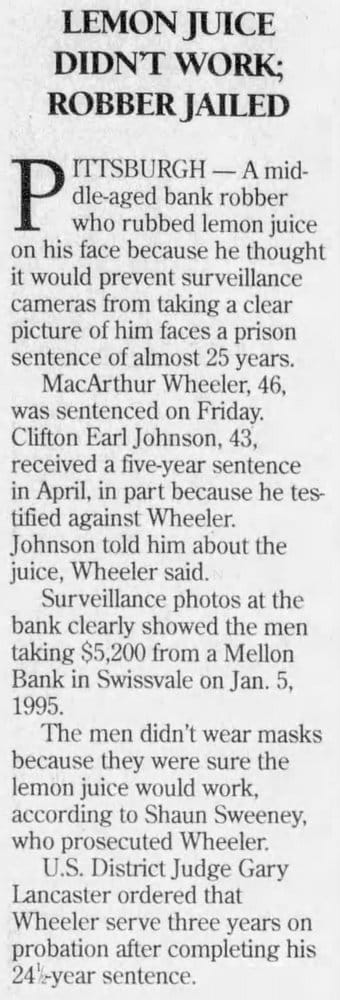

In January 1995, MacArthur* Wheeler, 46, and Clifton Earl Johnson, 43, robbed two banks in the Greater Pittsburgh area at gunpoint. Johnson had told Wheeler a trick he had learned: that by putting lemon juice on their faces, they would be invisible to security cameras, and could get away with crime.

Wheeler wasn’t sure he believed that, so he got some lemon juice and a Polaroid camera, put on the juice, took a photo of himself, and sure enough, he wasn’t in the resulting photo! Emboldened, the duo lemoned up and hit two banks. They were arrested hours later, thanks to the clear photos of their faces from the banks’ security cameras.

When arrested, Wheeler was incredulous. “But I wore the lemon juice! I wore the lemon juice!” he told police, which of course gave the cops a clue as to what questions to ask to elicit the story.

“But wait,” you might say. “What of the test with the Polaroid camera?” Well, consider Wheeler’s mental abilities: he didn’t even manage to have the camera pointed at himself when he took the test photo.

Johnson agreed to testify against Wheeler, and was sentenced to just 5 years in prison. Wheeler got 24-1/2 years, plus 3 years of probation.

Reading about this case gave Dr. Dunning the idea to look into the “inflated self-assessment” Wheeler made, and then look into whether it was simply a one-off obliviot, or a more meaningful concept that might apply to more people than just Wheeler. It was so much the latter that Dunning and Kruger’s work was funded by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health. Their paper was first published in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology in 1999 as “Unskilled and Unaware of It: How Difficulties in Recognizing One’s Own Incompetence Lead to Inflated Self-Assessments”.

* Most stories show Wheeler’s first name spelled as MacArthur; Dunning himself spelled it McArthur. Did Dunning reveal himself as a worse speller than his self-assessment indicated? Just something to think about….

2025 Update: Urban Legend?

So, there’s a later twist: supposedly, according to one, and only one, researcher who has been quite vocal online, the Centre Daily Times story is absolutely wrong about the facts of the Wheeler case. Let’s suppose that’s true: does that negate the Dunning-Kruger Effect?

In my opinion, no. Why not? Because Dunning and Kruger didn’t spend 13-1/2 pages of tiny typeset text to talk about Wheeler; he was just the introduction, the spark for Dunning to begin thinking about this topic. It doesn’t matter even if Dunning was sparked by a 100-year-old fictional short story, or the idea simply came to him because he was wondering why is it some people are so stupid, yet don’t know that they are stupid.

The bottom line is, the idea was sparked. He and Kruger then thought about it, researched it, tested it, analyzed it, and put it out in a journal article for others to think about, research, test, analyze, and refine. Which other researchers did.

And the premise that Dunning and Kruger put out was not that “People are so stupid, they don’t know that they’re stupid.” but rather that “People tend to hold overly favorable views of their abilities in many social and intellectual domains. The authors suggest that this overestimation occurs, in part, because people who are unskilled in these domains suffer a dual burden: Not only do these people reach erroneous conclusions and make unfortunate choices, but their incompetence robs them of the metacognitive ability to realize it.” [emphasis added]

Those are the first two sentences of their paper’s Abstract (which you might call an Executive Summary). Their thesis isn’t that some people are stupid; that’s rather obvious. Rather, it’s about why they don’t know that they’re stupid. They then go on to analyze four studies to see if that thesis held up, and found that it did. That’s pretty much what journal articles do: they put an idea out to say exactly how they have validated the idea, so that other researchers can run with it, offer more validation, or offer countering theories or studies that call the thesis into question. AKA refinement.

So it absolutely doesn’t matter whether whether Wheeler really did rob banks (he did, according to his criminal trial and subsequent imprisonment), tried to disguise himself with lemon juice (maybe he did; I’ve not found a police report or court transcript that confirms or refutes this), or anything else. Dunning was inspired by the story that said so, and came up with his thesis. The rest was up to his study design, which (along with its results) got published and is still out there for anyone to read. It seems to have held up pretty well in the decades since.

Whether the Wheeler lemon juice story is true is a different question, and even though my guess is that it probably is, the answer really has no bearing on the Dunning-Kruger paper.

More on the “Effect” in Wikipedia.

– – –

Bad link? Broken image? Other problem on this page? Use the Help button lower right, and thanks.

This page is an example of my style of “Thought-Provoking Entertainment”. This is True is an email newsletter that uses “weird news” as a vehicle to explore the human condition in an entertaining way. If that sounds good, click here to open a subscribe form.

To really support This is True, you’re invited to sign up for a subscription to the much-expanded “Premium” edition:

Q: Why would I want to pay more than the minimum rate?

A: To support the publication to help it thrive and stay online: this kind of support means less future need for price increases (and smaller increases when they do happen), which enables more people to upgrade. This option was requested by existing Premium subscribers.

Reminds me of one of my favorite quotes:

“The trouble with most folks isn’t so much their ignorance, as knowing so many things that ain’t so.” –Josh Billings

This kind of reminds me of this Calvin and Hobbes cartoon.

—

One of the best single panels of C&H. -rc

Unfortunately the D-K effect has been hijacked by people evidently suffering from it, who think they can close off an argument by shouting “D-K effect!” as if internet-text-based telediagnosis were a reality

If this isn’t the perfect description for the CA state legislative body and our Fed, I don’t know what is!

It sounds like The Peter Principle, where someone is promoted well above their level of competence so they can’t TRULY screw anything up… Or the US Government.

I just saw a Facebook post last week, “If you are dead, you don’t know you are dead. So it’s only bad for the people around you. Same with stupidity.”

I don’t think it wise to comment on the tag.

—

But is it wise to comment that you’re not commenting on the tag? -rc

Finally! An answer! I followed the links and read more about the D-K effect, and it explains my situation perfectly.

My mother always made my sister and me feel as if we were just one step above the village idiot. As a result, I tend to become very impatient with people who don’t find things as easy to do as I do. I’ve always referred to my condition as an Inferiority Complex on Steroids. “If anybody as dumb as I am can get this, what’s the matter with you?”

It would seem my mother was a carrier of the dreaded DKE. Thanks!

—

Glad to shed light. -rc

For Dani, from Bradshaw, MD: It does you no good to lose patience with “THEM” as they won’t understand anyway, and become restive and their acuity falls. I simply treat them as if they are just a little slow. It IS frustrating always having to fill in the blanks…

Dunning deserves credit for recognizing the pot/kettle nature of this observation. Each of us is potentially guilty of the same arbitrary assumption that we’re right and the other person is either too stupid, or too brainwashed, to understand. Constantly questioning facts, assumptions, beliefs and attitudes consumes mental and cognitive energy, and can inhibit action. We’re designed to operate on a world model which allows us to react without conscious thought or continuous decision making; life is a lot more strenuous without certitude.

Unfortunately, mythology is also a methodology for social coherence, and many of the things we know that just ain’t so are taught in schools, as part of a process which, in general terms, is designed to turn out new citizens who think the same as their parents, and won’t upset the status quo.

Yes, “Just because you don’t know the answer doesn’t mean that someone else does.” I find that comforting.

The more you put into a brain, the more it will hold. However, when a person prohibits cognitive input and shuts off the information flow going in, their reasoning processes fill in the blanks. The resulting output is certainty of concepts that are at best assumptions. Conspiracy theorists have adhered to this principle for hundreds of years. Interestingly, even they seldom agree.

Fortunately, as my law enforcement pals keep reminding me, stupidity is still legal. Fear the day it is not.

I worked as an English-Spanish interpreter for many years and I used to say about interpreter wannabes that the only thing worse than “interpreters” who don’t understant English (or any other second language for that matter) is “interpreters” who THINK they understand it! I’ve seen it: they’ll enthusiastically spit out whatever comes up in their silly minds and the person they interpret for won’t have a clue they’re actually being completely misinterpreted!

I also believe the effect to be stronger in educated individuals. I do IT at Hebrew University, and let me tell you there’s no one as incompetent with computers as educated technophobes. The biggest problems come up when they try solving problems on their own….

I propose the Morrison Principle: People who have verified the Peter Principle by their position should simply be demoted to their first level of competence. I know, I KNOW! It ain’t gonna happen but one can hope.

I remember reading about the announcement of the D-K Effect in my local paper when I was 13 and thinking, “This is just stating the glaringly obvious”. The less you know, the more you think you do. You’re ignorant of being ignorant. In fancier terms, how much you think you know is inversely proportional to how much you actually know.

Wouldn’t it be nice if everyone could be intelligent for one day, just so they know what they’re missing?

There’s also a corollary … the smart people who always underestimate themselves. They (we, on too many occasions) assume that since it’s so easy for them, it must be easy for everyone else too.

I came up with a different working definition for IQ. It’s nothing but the marks on the outside of a measuring cup. It says nothing about what, if anything, gets put in it. It doesn’t take many Mensa meetings to realize that IQ doesn’t mean “smart” in useful terms.

—

Not always, anyway! I’ve said something similar before: just because they’re smart doesn’t mean they have a lick of common sense. And that can certainly be true even if they are well educated. -rc

My mother used to say that her father-in-law had all the education (a doctorate in chemistry by age 23) and her father (who only made it to eighth grade before having to work to support the family due to his father’s alcoholism) had all the common sense.

While there may be no cure for the DK Effect (otherwise known as Cranial-Rectal Insertion) there is the possibility of management of the effect using Cranial-Rectal Extraction, a technique I highly recommend, and use myself on a daily, sometimes hourly, basis ; ) Two books that have been very helpful in understanding the the need for this technique are On Being Certain by Robert A. Burton M.D. and The Knowledge Illusion by Steven Sloman/Phillip Fernbach. If you do read these books, I’m sure you’ll begin to recognize the source of those seemingly random popping sounds you may have heard, (some of them even in your immediate vicinity?) : )

I often wondered at my competence before I retired from nursing. Being “called out” for little, insignificant things on the job, while at the same time not being recognized for the overall accomplishment of a job well done, also called into question my overall competence.

Big Bummer on both sides.

Bosses, giving your workers complements during the work day may actually increase your workers productivity.

—

GOOD bosses know that, and do it. That yours didn’t calls into question their overall competence. -rc

People who really do suffer from impostor syndrome hit the valley of despair and do not have nearly that upward curve….

—

Yep, it takes actual learning to climb the Slope of Enlightenment. -rc

No, it’s more that they gain competence without increasing confidence.

—

Ah, I didn’t parse your comment correctly. That’s where a good boss comes in, with encouragement and mentorship. -rc

Back in high school I got a little ahead of myself when I had just learned some soldering techniques in gold and silversmithing. I executed some joints so perfect that they were virtually invisible. Soon after I realized that I had actually learned just enough to be dangerous when I attempted a repair that had a hollow piece in it. It blew up like popcorn. It may be called the Dunning-Krueger effect now, but I always called it knowing just enough to be dangerous. Considering some of the jobs I’ve had, that has been quite literal.

This helped me understand so much when I first encountered it….

The first rule of Dunning-Kruger Club is: if you don’t worry that you might have Dunning-Kruger, you have Dunning-Kruger.

Second rule of Dunning-Kruger Club: we all have, have had, or will have Dunning-Kruger, usually all three at once, so just deal with it.

Third rule of Dunning-Kruger Club: accepting that you have or are likely to have or get Dunning-Kruger is your best bet for dealing with it.

—

“If you have Dunning-Kruger, admitting it is the first step toward a cure.” -rc

During the early years of my first “real” job (in my chosen field), I had a conversation with a boss regarding this very topic. Regarding people who have little competence, he said to me “They don’t know how much they don’t know.” So my boss, Charlie, should have received the Ig Nobel Prize in Psychology 20 years before Dunning and Kruger.

—

Too bad your boss didn’t know that in order for it to be considered research, you have to publish! -rc