This is a very unusual Honorary Unsubscribe as it’s going to be quite long (several parts), and in a different, and personal, format: I knew Dave Farber, and spoke with him at length over the course of several years about his legacy.

On Saturday, February 7, Dave sent a URL to a group of friends that he thought we would find of interest. The article, from Science, was just the sort of thing his geeky friends would be interested in: A hack-proof internet? Quantum encryption could be the key.

The articles I sometimes link to at the top of True newsletters — the “Other Good Reading” section? Some of those were from Dave via that channel.

A few hours after sending that, David Jack Farber died at his home in Tokyo, Japan. He was 91.

Farber was one of the first Premium This is True subscribers, beginning in early 1997. I spoke to him a couple of times on Zoom over the past several years, interviewing him on the record. All quotes here are verbatim to me personally unless otherwise noted. Farber was always generous with his time: he was happy to give interviews and did many with a wide variety of industry historians and researchers.

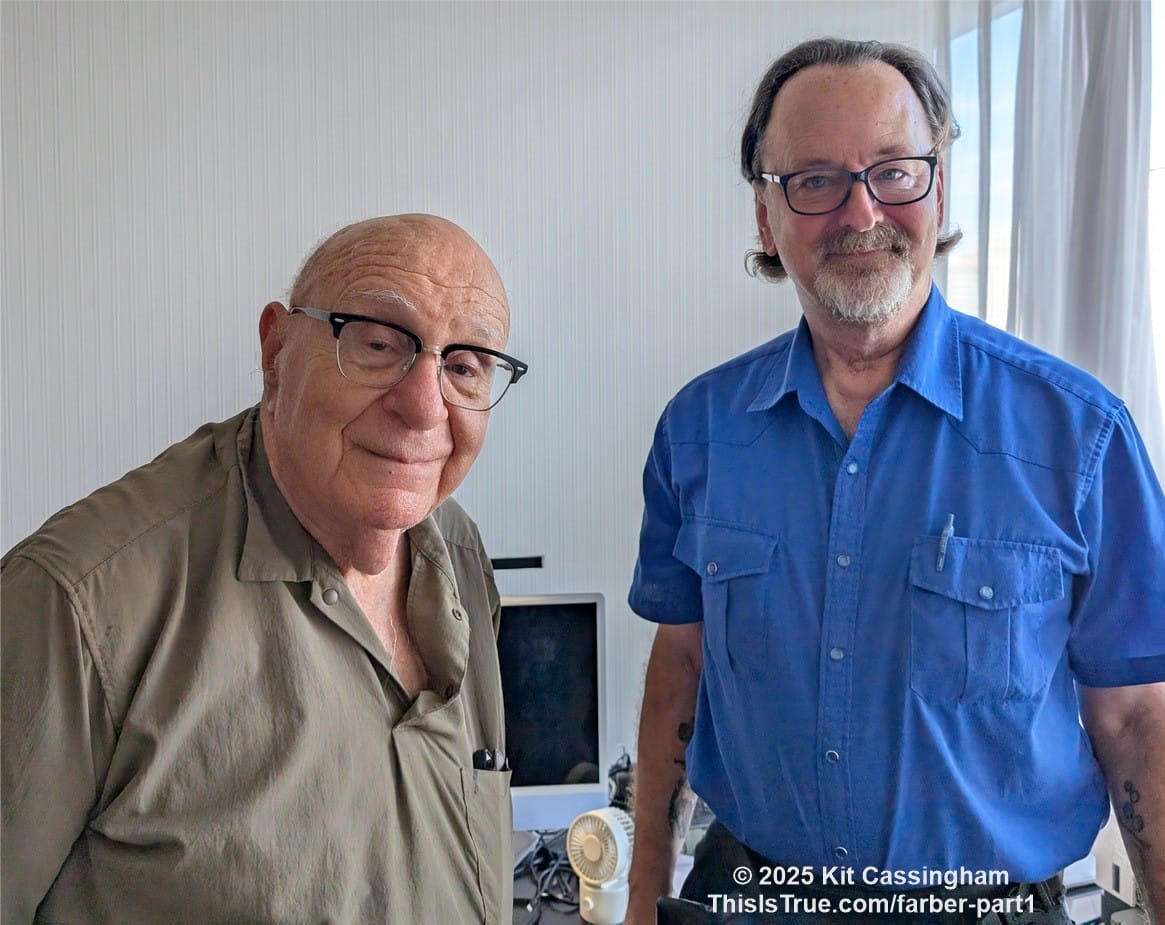

When he saw in True that Kit and I were approaching Japan, he invited us to come and take him to lunch. We met him at one of his haunts, and accompanied him to the grocery store. He lived in a complex which had all of this indoors: we went from place to place without even going outside, which was great because it was hot in Tokyo in August. He then brought us up to his apartment for another chat, which I also recorded with his permission.

After the several hours this all took, he walked us through the maze to the train station so that we wouldn’t have to go outside.

Dave read True avidly, and sometimes shared bits from it on his own mailing list, Interesting People, which mailing list I was initially aware of because my buddy John Bosley would often forward me items from it. One of the stories coming later in this series on Farber: how IP got started. It involves, weirdly enough, another important figure from the history of computing …who was also an early Premium subscriber.

Part One: The Idea Man

Farber had a knack of being in the right place at the right time. After graduating from the Stevens Institute of Technology in Hoboken, N.J. (Masters in Electrical Engineering in 1956, and a Masters in Mathematics in 1961), he was planning on going on for his Ph.D when he happened to speak to someone who worked at Bell Labs, the “Ma Bell” research and development arm of AT&T, who invited Farber to visit. The Labs were nearby, in Murray Hill, N.J., so Dave went.

“I got into a big fight,” he told me in 2023, with a Bell Labs engineer who was tasked with designing a new telephone system. “I thought he was wrong and I told him so. And we had a big discussion. When I left his office, his secretary said, ‘I don’t know what you did, but human resources wants to talk to you.’” The project manager liked what Farber had told him — even the “you’re wrong” part — and wanted him on his team. “It was intriguing, enough so that I deferred my graduate school, which was a smart move in retrospect.” [Unfortunately I didn’t pursue this to be sure, but he likely had been talking to H. Earle Vaughan, the lead engineer responsible for designing the Electronic Switching System at Bell Labs.]

ESS

Farber was hired to help design Electronic Switching. At the time, the telephone network relied on electromechanical switches, huge racks of relays and moving parts that physically made the connection from one subscriber’s line to another. They were the technological replacement for human operators connecting calls with cord boards. They had been refined over decades and could handle the growing numbers of lines, but they were mechanical: every call required physical movements, contacts opening and closing, and thousands of parts that wore out and needed continual adjustment and maintenance. That not only scaled up to be high in cost, but it was always destined to be a “Plain ’Ol Phone System” — POTS, as it eventually became known, pretty derisively.

Bell Labs already knew the future was electronic and computer controlled to make switching faster, more reliable, more efficient, and far easier to update with new features. Farber wasn’t there to wire things up: he played an integral part of the design of ESS-1, the first Electronic Switching System.

Not that it was cutting edge by today’s standards. “Looking back at it, it was an absolute nightmare. It was right at the edge of technology. It was transistors, but transistors at that point were not exactly developed,” he said. “Just a mishmash of technology, but it worked. And I was part of the group that was designing this monstrosity.” But it was a key time for Farber: “The thing that actually triggered my movement into computers was that we were trying to look at how could you analyze the switching networks inside telephone systems.” Switching networks inside telephone systems: the germ of computer networks was planted in his head. I’ll come back to that shortly.

Time to Go? Nah!

Farber decided that it was time to go back and get his Ph.D. He called a friend at Bell Labs, Dick Hamming, who was president of the Association for Computing Machinery from 1958 to 1960: “I said, ‘I’m going off graduate school.’ He asked a question which actually defined my career, mostly. He said, ‘Why? You’re at the center of computer science at Bell Labs. Nobody’s doing as much as we’re doing here.’ He was right. So I stayed for 15 years.”

One problem that Dave came up against was that the mainframe computer Bell Labs had, the IBM 704 (this was still early enough that it was vacuum tube based!), was poorly documented and difficult to program. A colleague “was trying to do formal algebra on a computer. There were just no real tools available for doing it that made any sense. And so we sat down and said, ‘That sounds like fun. Let’s see if we can develop a [programming] language to help him.’”

Farber joined with Bell Lab friends Ralph Griswold and Ivan P. Polonsky and came up with SNOBOL, which was later backronymed as “StriNg Oriented symBOlic Language”. But it was really named, Farber said in 2008 in Interesting People, when Griswold said, “We don’t have a snowball’s chance in hell of finding a name” for it, and they all yelled “SNOBAL!” at the same time in the “spirit of the BOL languages” like COBOL. “We then stretched our mind to find what it stood for.”

California Sun

Dave then got a call from RAND Corporation, the southern California think tank, which offered him a job. “So I decided to leave Bell Labs and go west, which was probably a good move in hindsight because Bell Labs at that point was running into resistance from the Public Utility Commissions, who didn’t want AT&T to put as much money into R&D as they were doing and keep the rates low,” he told me. “That changed it all, the whole feel in the Laboratories.”

The University of California at Irvine caught wind of Faber’s presence and asked if he would consider teaching there. “I had taught a class at Stevens, where I got my degrees. An evening class, which also proved to me that nobody wants to attend the evening class after a day of work. It’s a terrible way to get educated.”

But there was a bigger problem: “I realized I didn’t get an earned Ph.D,” though “I really wasn’t worried because if academic life didn’t pan out or I didn’t like it, I’d just hold up my hand and there were plenty of people who were happy to hire me.” As we’ve been seeing.

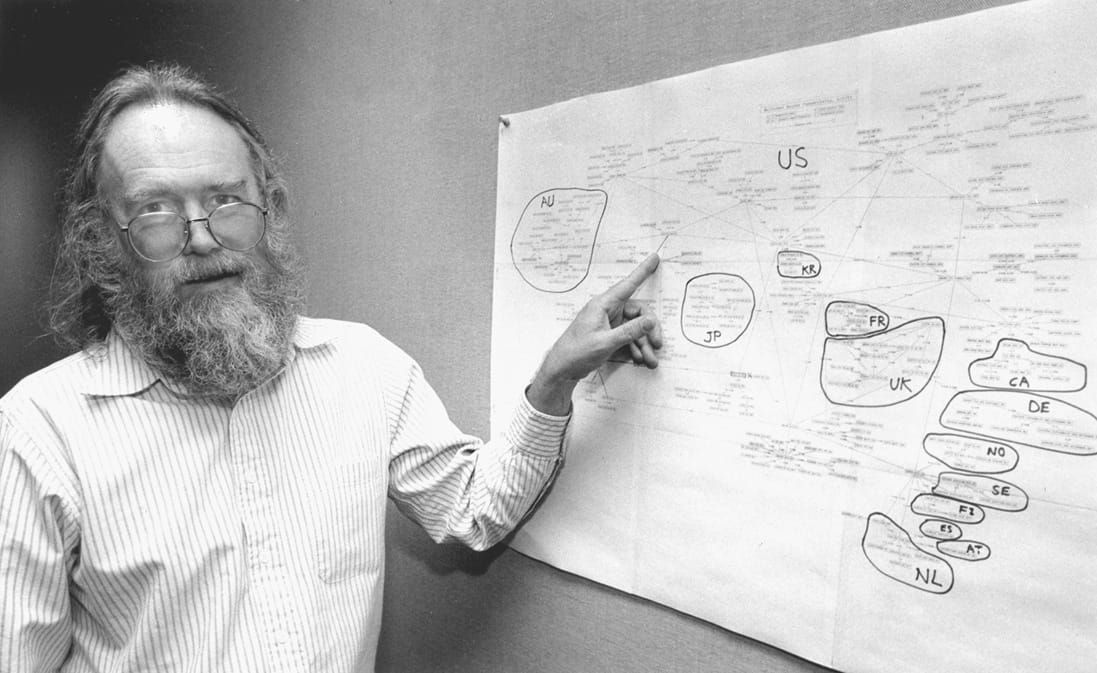

The school offered him a deal: come for two years and figure out what he wanted to research there. If he could attract enough funding within two years to support himself, he’d get tenure. If not, “you’re out. I applied to [the National Science Foundation] for a research project which I had thought of.” He asked for $250,000 per year to create DCS, the world’s first operational distributed computer system: a network of three minicomputers interconnected with a token ring local area network. It was 1970, and NCF was game: it granted the funding request.

DCS

Dave’s idea was radical: instead of one giant mainframe computer, jobs would be split up among minicomputers , which could be different models, or even be from different manufacturers and have different capabilities, and do different parts of the job. Networking was a core component, not merely a means of hooking up a terminal. It was fault-tolerant (the whole could keep running even if one of the machines crashed), it was scalable.

It forced computer designers to think seriously about distributed operating systems, protocols, naming, and resource sharing — problems that barely existed in single-machine computing. In short, Dave’s DCS anticipated the entire direction of modern computing: clusters, client-server systems, cloud computing, microservices, and more, none of which had ever previously made sense without the mental shift DCS represented.

Or, as Dave put it to me: “It was really a somewhat revolutionary idea.” Pretty much, a Farberism. (Dave was well known for Farberisms: his slightly sideways sayings that came off the cuff. “It is better to have tried and failed than never to have failed at all.” Or, “From here on up, it’s down hill all the way.” Or, “A nickel ain’t worth a dime anymore.”)

Because of being the mind behind this shift, Farber understood everything that was needed: open, interoperable networking between different kinds of machines, which helped shape thinking around host protocols, distributed applications, and networked services. Farber became a connector and catalyst, bringing together researchers, ideas, and institutions that were working to connect their computers together to share resources. In other words, building the early Internet.

Right place, right time.

And the Right People

DCS was a smashing success. “It also, more interestingly,” Dave told me, “developed some really good graduate students. Some of them went on to essentially make names.” (Another Farberism)

He named Paul Mockapetris, for instance, who earned his doctorate in information and computer science from Irvine in 1982 under Farber: he was there as DCS was developed. The next year, Mockapetris invented DNS, the Internet’s Domain Name System, which is why you can type “thisistrue.com” into a browser and actually reach this site instead of having to remember a string of numbers, or send email without having to manually specify which mail server should receive it, since the “MX record” in DNS tells the sending computer where to deliver it.

“I had Jon Postel as a graduate student at UCLA,” Dave continued. “It was a fun time.” He didn’t have to tell me who Postel was (alas, he died after heart surgery in 1998, at just 55). Postel was one of the architects of how the Internet works day to day. He made sure the Internet’s basic rules were written down, agreed upon, and followed. He is best known as the longtime editor of the “Requests for Comments” (RFCs), which are the documents that define how Internet technologies work. As editor, he decided what counted as an official Internet standard, shaping how those standards were written, and keeping the whole system coherent, particularly over time. If engineers around the world wanted to know how a protocol was supposed to work, they looked to the RFCs — and for decades, Postel was the expert guiding that process.

Postel was also deeply involved in email. He didn’t single-handedly invent SMTP (the Simple Mail Transfer Protocol — there’s that word again, “protocol”), but he was one of the key figures who defined it, refined it, and standardized it so that email systems built by different companies and universities could reliably talk to each other. In practical terms, that’s why you can send email from one system to another across the world and it just works. He played a similar role for many other core Internet protocols: not always the sole inventor, but the person who made sure the rules were clear, consistent, and usable.

If that wasn’t enough, Postel also ran IANA: the Internet Assigned Numbers Authority. Essentially, IANA is the Internet’s master address book and registry. Its job is to keep track of things like protocol numbers, port numbers, and the top-level coordination of domain names so that two different systems wouldn’t accidentally try to use the same identifiers for different purposes. Postel was the trusted steward who made sure everyone was using the same map. When people say, only half jokingly, that “Jon Postel was the Internet’s traffic cop,” this is what they mean. More importantly, the systems he set up were robust enough to survive his death.

In a profile of Postel, The Economist, the British news magazine, dubbed him “God of the Internet” to convey just how central and influential his technical influence was on the early Internet. Postel didn’t like the label, modestly pointing out that the Internet worked as well as it did because of shared cooperation.

Yet, if Farber’s students were so influential after learning at his feet (or, if you prefer, by standing on Farber’s giant shoulders), what does that make Farber? He is commonly referred to as the “Grandfather of the Internet.”

Part 2

In Part 2, Dave heads back east, how Interesting People started …and who suggested it. Coming soon. You can sign up for notification of new posts when they appear here: look for “Blog Post Notifications” in the sidebar (which is below this if you’re on a phone).