In Part 1 of my more-personal-than-usual style of Honorary Unsubscribe for my friend (and long-time reader) David J. Farber, I ended by saying that next, I’d talk about how his own email “newsletter” of sorts, Interesting People, commonly referred to as IP, started. Let’s jump right in.

Interesting People

In a call with Dave in 2023, I mentioned that he had been doing IP for a long time. “Long, long time,” he agreed. “If you got a minute, I’ll tell you how that happened. What’s his name? … Oh, I can’t remember his name right now, but he was a senior IBM executive who went to the National Science Foundation as director of NSF. I should remember his name. He was a good friend.”

He was thinking of Erich Bloch, who started working at IBM in 1952, fresh out of college. Bloch had worked on IBM’s System 360. If that sounds familiar in the context of This is True, you probably read the post about “Mythical Man” Fred Brooks, its chief architect and long-time True reader, who I wrote about in 2021. Bloch was on Brooks’ System 360 team, and went on to be the Director of the NSF from 1984 to 1990.

“Anyway,” Dave continued, “I met him in the hall. I was in NSF. I was often down in Washington. I asked him how goes things. He said, ‘Fine,’ but he doesn’t have the time to look at the ’net and keep his hands on the pulse of things. So I said, ‘Look, why don’t I send you anything I find interesting?’ So I sent him some stuff” by email. Bloch then forwarded it to others he knew would also find the messages interesting — such as his old boss from IBM, Fred Brooks.

“And after a week, he said, ‘Hey, could you add and send it to my colleagues at NSF? And my colleagues at IBM?’ And it grew from there. I guess it exploded.” Interesting People was born: it was 1985, and Dave was a professor at the University of Delaware.

The year before, Ira Fuchs, Daniel Oberst, and Ricky Hernandez wrote software to run on IBM VM mainframes: LISTSERV. Fuchs was the co-founder of BITNET, a network of east coast academic computer systems that was a precursor to the Internet. While Dave didn’t mention LISTSERV, it’s very likely that it, as the first mailing list software, was used to manage the “exploding” interest in the IP list. The people that Dave knew, like Bloch and Brooks, certainly helped that explosion of interest, and Dave absolutely had access to bigger computers, and the professional network to get a copy of LISTSERV to handle the IP list if it wasn’t already available to him at the University of Delaware.

Many people (and ChatGPT — snort!) put the founding of IP as May 1993, since that’s when IP’s online archive begins. But no: it was 1985, and likely most of the earlier archives have simply been lost.

And then, Dave continues, “the White House formed the National Security Task Force.” [I’m not able to find a Task Force of that exact name from the mid-80s, but Reagan did create several such groups around that time.] “And one of the people on the IP list said, ‘How about adding all the people on this task force to the IP list? Because you’re getting better information than we’re getting from the standard places.’”

The IP list grew to around 30,000 recipients, though when he moved to Japan, he didn’t pay as much attention to it, so many dropped off. “It’s still maybe 15,000 people, in that range,” he said in 2023. The reason it worked, he said, “is that you have a moderator. Nothing goes on the list except through me. Nothing. You can’t directly mail it to the list. And so it’s up to me to be the judge. If you like what my choices [are], you stay on the list. If not, you get off the list.”

Has he ever made a mistake in sending something to the list that, perhaps, was overhyped, or even just plain wrong? Sure. “Every once in a while, I make an error, and post something that’s not quite accurate, but not often. And the reaction is fast from the list.” The readers correct him, and he posts an update. “And that’s what makes it valuable.”

He paused briefly, then continued: “You’re doing a simple version of it [with This is True]. I believe that at some point it’s going to be the way that at least news and information is distributed — that you’ll have an editor. If the editor does what you like, you’ll stay with him. If not, you’ll go elsewhere. So it’s the old newspaper, radio, in some sense, thing. And the IP was one of the examples of that. And you get thick skin because I tell people, you may not like what I say. If you don’t, send me a polite note. And if it’s decent, I’ll distribute it. I’m open to all views, but I’m not open to ranting, raving and lies. I’ll filter those and throw them in the garbage can. I think that’s the only way that we’re going to make sense out of the mess we’re in now.”

No wonder he — and Fred Brooks — liked True!

Gatekeepers

But let’s back up just a bit, since Dave’s point here is important: news organizations are letting us down. They kowtow to advertisers, to people in power, to publishers’ whims. Who is lost in the shuffle? We are. The readers.

For example, consider the Washington Post. Founded in 1877, it was powerful enough to unseat President Nixon over Watergate. It was bought by Amazon billionaire Jeff Bezos in October 2013, and he was mostly hands off, and escaped the face of so many papers that were falling dead all around the country. I mean, we really need strong journalism in the nation’s capital.

The Post’s health changed big time shortly before the 2024 Presidential Election, when Bezos stopped the paper from endorsing Kamala Harris. Editors, reporters, and columnists resigned in protest, but that was nothing compared to what the readers did: they canceled their subscriptions in droves — as Dave put it, “If the editor does what you like, you’ll stay with him. If not, you’ll go elsewhere.” Their readers went elsewhere, and have not returned.

The Post hasn’t recovered. On February 4, it was announced that as many as 300 Post employees would be laid off, and even local news coverage will see “deep cuts.” [Source] Three days later, Post Publisher Will Lewis announced his resignation.

As news organizations slide into oblivion — even the Post — who will take up the slack? “Creators”. That’s definitely not my term, but like “Influencer” (thank goodness no one has accused me of being one of those!), it has become an industry term to mean someone with a niche that “creates” “content” on a subject you care about. (Influencers, meanwhile, simply take money to pimp products for their “followers”.) The hard part is, finding someone creating content in a professional and sustainable way that you can relate with, whether they create writing, podcasts, videos, or other. And, of course, doing it in a way that the readers can trust.

When you find those rare folks, subscribe, spread the word, and support them.

It’s getting somewhat easier to find such creators since there are newer platforms making it easier for us, like Medium and Substack, both of which I’ve tried myself, but gave up on. I’m lucky in that my tech background has meant I could piece together my own tools, but they take time to maintain. Unless Substack gets too greedy and/or unfocused, they will probably soon dominate as an important platform for Creators.

Medium got too buttoned up for me, making it harder to explore and find someone you resonate with. Substack seems to have a better platform for discovery, but many feel there’s a problem there with ethics, which gave many Creators, such as me, pause. We’ll see!

But to not get too far from the point, Farber saw this Creator era coming years, maybe even decades, ago, even if he didn’t call it that. He had vision when he went to Bell Labs, to Rand, to U.C. Irvine, and beyond. He had the vision to spin out ideas and see what was really going on not just because he was smart, or had technical knowledge (though he certainly had both), but he also knew so many of the players and, when he saw synergy, introduced those people to each other, and then solicited their feedback to pass along to his network, such as through Interesting People.

I did much the same networking with early online creators, linking them up with each other, putting on conferences, and helping them to find their niche. You know many of their names.

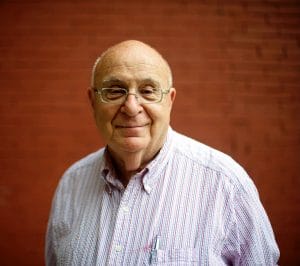

Dave’s wide-ranging knowledge plus that kind of networking creates incredible value, and he was still loving it, and nurturing students, even as he passed 90 years old. “I don’t want to retire,” he told me in 2023. “I enjoy working with students. I enjoy thinking. I will probably continue to be active until I keel over.” And he did, sending out one last message to his friends list on Signal hours before he died.

Heading Back East

At the end of Part 1, Farber was still at U.C. Irvine, in California, mentoring students like Jon Postel and Paul Mockapetris …and getting antsy. It was 1977. Right place, right time? “The head of the EE Department for University of Delaware stopped by and said, ‘Why don’t you come back to the east?’” He was ready, telling me that “California can get you after a while. And family was in the east and we had two children then. OK, so I went back east and that’s where I got involved in the NSFNET.” He paused briefly to gather his thoughts: there were some more steps before he got to the NSFNET.

“This was sort of the age of when the U.S. was putting a huge amount of money into developing computer science departments — the Cold War phenomenon. So you had these departments all over the country that had maybe one person in program, language, and operating systems.” The problem was, there weren’t all that many teachers with computer expertise available, so the departments tended to be small.

“And so we proposed to the [National Science Foundation] that we develop — use the ARPA technology, simple forms of it — to allow all the computer science departments to be able to use the Internet” not “only” to share resources, but to be able to talk with each other, to do research together, to write papers together.

He was speaking from personal experience: in late 1976, he wrote a paper with Paul Baran, who had worked at RAND on computer networking, and how to make such a network survive a nuclear attack — the very basis for the Internet. The paper, “The Convergence of Computing and Telecommunications Systems”, talks about how “the cost of communications and computation” was dropping, which would enable “new services” that will allow for collaboration among researchers — if researchers could get beyond the obstacles put up by lawyers to protect their clients’ interests: giants like AT&T and IBM.

In that paper, it was necessary for Farber, who was still at U.C. Irvine, and Baran, who was working in Palo Alto, to explain what they meant in very basic terms, even for their intended audience: “This article was written by two authors 500 miles apart, using a computer communication system. Each writes on the same sheet of ‘paper.’ Each amplifies, modifies, and clarifies the words of the other. Misspellings are corrected, and the order of phrases is changed. Each author takes his turn tidying up the modified manuscript by pressing a few buttons and giving a few commands. This takes care of the nitty gritty in paper writing, gobbling up the blank spaces and even justifying the right margin. Discussions on content and outlook take place with the use of the same computer communications-based message systems. The method used to produce the article you are now reading is not tomorrow. It is today. Tomorrow, computer communications systems will be the rule for remote collaboration.”

Sure that’s obvious now, but that was published almost exactly 49 years ago, in the 18 March 1977 issue of Science.

But, they continued: who needs AT&T or IBM? “Powerful computers have become cheap and will get cheaper. The explosion of the computer hobby market during the last year and a half has been remarkable. There are now 150 specialty stores selling low-cost computers in hobby kit form. More computer development work is being done by hobbyists today than by computer science researchers funded by public agencies.”

You’ve read about that sort of thing right here in this blog — recently! For instance in my discussion of Dan Sokol (Part 1, Part 2, Part 3) from almost exactly a year ago.

CSNet

At the University of Delaware, Farber was still thinking computer networking — building upon his work at Irvine that led to DCS, as discussed in Part 1. He made a pitch to the NSF again. “We got money to do it with some strings attached,” he continued. “They said, ‘We’ll give you three years of funding. If at the end of three years you can’t make it self-sufficient, that means that the field doesn’t want it.’ It was smart. We made it self-sufficient. And in fact, it grew.”

The funding, which ran from 1981 to 1984, was for CSNET — the Computer Science Network. Its purpose was to extend networking benefits to computer science departments at academic and research institutions that could not be directly connected to ARPANET due to funding or authorization limitations. It played a significant role in spreading awareness of, and access to, national networking, and was a major milestone on the path to development of the Internet.

“And part of that was that we, in fact, 35 years ago, Larry [Landweber] and I came to Asia with tapes in hand. I made tapes by hand with the software.” And flew to Japan with that software, and then South Korea. CSNET would not be just for U.S. universities. It was Landweber, by the way, who made a pivotal decision as one of the creators of CSNET: he chose TCP/IP as the networking protocol. That is what the Internet still uses today.

“And so we expanded into international. And then I was chairing the NSF Advisory Board on Networking, and we first opened it up to companies which supported academic research. And then we had an endless parade of people from other parts of the academic community who came in and said, ‘Can’t we use your facilities so we can interact with our colleagues at the school?’”

They saw the value immediately.

But, he continued, “computer science departments were not in the business of running computing centers. So we essentially convinced NSF to form NSFNET, which put the money in to be able to move the network stuff to the computing centers and spread it as a service for campus. And that took off. And then I guess the next step was the commercialization of it. And we did a reasonable job. We made a lot of mistakes. A lot, a lot of mistakes, but it worked anyway. And so off we went.”

“Just out of curiosity,” I asked Dave since he had brought up commercialization, “at NSF, did you know a guy named David Staudt?”

“Yeah. I can’t put a face to it, but the name’s familiar,” he said.

“He’s a friend of mine and another reader. And his last job at NSF was to help commercialize the Internet. He was very proud that This is True was an early commercial success online.” [Dave Staudt died in 2024, I wrote about him briefly, too.]

“Yeah, the field was ready for it,” Farber said. “There’s an interesting question I’ve always had a debate with people on. What made the ’net expand as much [as it has]? Initially, yes, companies used it: they had PDP-10s or whatever your favorite machine was. But what made it go the next step into what it is now? And I think that was more dependent not on a browser — we had browsers back then — but on the personal computer. When the PC came out and it was cheap, and a couple of kids at MIT brought over the network code to run on the DOS. That terrible operating system Microsoft had, no worse than most. And suddenly these PCs at home through telephone lines — usually, of course, the couplers — could use the ’net. That I think was the thing that sparked things. Suddenly, crowds of people came in. Unix machines were very common and they’d run on small computers, so you could afford it.”

Regular people getting online in the early 1990s with plain old home computers. It was an amazing time, and exactly why, in 1994, I started This is True and put plans in motion to leave my job with NASA to work online full-time for the rest of my career. I figured that, as a writer, I could probably keep going pretty much as long as I wanted. I might slow down, but continual advances in technology would probably might help me continue long past usual retirement age.

“I think that triggered the expansion. But the thing that always amused me is that people will stand up and tell you that they knew all along it was going to go the way it went. And my general observation is how come you’re not rich in a Bill Gates kind of way? Very few people understood it was going to go the way it went. A lot of people understood it was going to be very good for industry, academia, et cetera, but not the blossoming that happened. And that’s an interesting byproduct.”

Hell: even Bill Gates didn’t know the Internet was going to explode the way it did!

Part 3

Yes, there is still quite a bit more to bring you from Dave: When it comes to early computing and Internet, who hasn’t received the recognition they deserve? Who was his mentor? Why there is so little basic research going on now. Why he was in Japan. And what he was most proud of from his own career.

And I haven’t even started reviewing my in-person meeting with him in August, which will almost certainly result in Part 4.

You can sign up for notification of new posts when they appear here: look for “Blog Post Notifications” in the sidebar (which is below this if you’re on a phone).

– – –

Bad link? Broken image? Other problem on this page? Use the Help button lower right, and thanks.

This page is an example of my style of “Thought-Provoking Entertainment”. This is True is an email newsletter that uses “weird news” as a vehicle to explore the human condition in an entertaining way. If that sounds good, click here to open a subscribe form.

To really support This is True, you’re invited to sign up for a subscription to the much-expanded “Premium” edition:

Q: Why would I want to pay more than the minimum rate?

A: To support the publication to help it thrive and stay online: this kind of support means less future need for price increases (and smaller increases when they do happen), which enables more people to upgrade. This option was requested by existing Premium subscribers.