In This Episode: Colorado, having seen constant partisan manipulations of redistricting in the past — Gerrymandering — actually did something about it, and did something radical in the process: they exercised Uncommon Sense.

064: The Line in the Sand

How to Subscribe and List of All Episodes

Show Notes

- Help Support Uncommon Sense — yes, $5 helps!

- The cartoon and photo of Bernie Buescher are included in the transcript below. See also the first comment.

- For full details and language about Colorado’s Constitutional Amendments see Colorado Amendment Y, Independent Commission for Congressional Redistricting Amendment, and Colorado Amendment Z, Independent Commission for State Legislative Redistricting Amendment, on Ballotpedia.

- The Amendments’ supporting web site is no longer online, but the Internet Archive has it. This link takes you to the last snapshot of the site before the election.

- TEDx is the local, independently licensed version of the main TED Conferences. Grand Junction, Colorado’s, run yearly. Details here.

Transcript

It’s Census time in the United States, and one of the most important uses of the resulting count is to determine our representation in Congress — you and me. The people of the state of Colorado, having seen constant partisan manipulations of redistricting in the past — Gerrymandering — were fed up enough to actually do something about it, and they did something radical in the process: they exercised Uncommon Sense.

Welcome to Uncommon Sense, I’m Randy Cassingham.

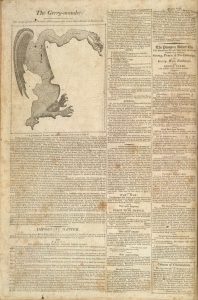

Gerrymandering goes way back, but not enough of us really understand what it means, and hardly anyone knows where the word comes from. In 1812, the governor of Massachusetts signed a law to redistrict the state to benefit his own party. The political cartoonist at the Boston Gazette newspaper looked at the resulting map and added a head and wings to the northern district, making it look like a giant salamander wrapped around the state, which the newspaper published on March 26, 1812. They named the newly mythical beast after the governor, Elbridge Gerry, spelled g-e-r-r-y. The result: the Gerry-Mander, which we now pronounce “jerry-mander”. I’ll include the cartoon on the Show Page.

But what is Gerrymandering really? By using voting records to redraw districts in convoluted, non-intuitive ways, it’s possible to make most or all of the districts have a minority of the opposition party so that it’s much more likely for the party in power to keep their seats, and stay in power. Ever since when given the chance both Republicans and Democrats have been doing it. In perhaps a bit of historical irony, Gerry’s party was the Democratic-Republican Party, which 12 years later splintered into two different parties: the Democrats, and the Republicans.

The problem, of course, is this sort of partisan manipulation results in the election of “representatives” that aren’t actually representative of the voters.

In 8 of the past 10 redistricting efforts in the state of Colorado, the redistricting done by the incumbent legislatures were so Gerrymandered that the process ended up in court, and judges ended up doing a lot of the shaping of districts. But guess what? Judges can be partisan too.

Enter Bernie Buescher, who served two terms in the Colorado General Assembly (the state legislature), who was then appointed by the governor to serve as the Secretary of State. After a term in that office, he was the state’s Deputy Attorney General, and he left politics in September of 2014.

Among other duties, the Secretary of State supervises elections, and sees the ins and outs of elections more deeply than the average politician. Buescher came away from his political career with a lot of friends and contacts — and a desire to change “politics as usual” to make the system more responsive to the interests of the voters.

In civilian life as an attorney, Buescher decided to leverage those contacts to make a difference: he wanted to end the unfairness of Gerrymandering in the state no matter which party benefited from it. As it happens, Buescher is a Democrat, but when you really get down to it, this isn’t a partisan issue, at least on the macro level; it certainly is when it’s being done by one party or the other, but since it’s done by both parties it’s unfair to one side or the other each time, and no one wants to argue these two wrongs make a right.

Worse, it promotes partisan divisiveness. “It’s hard to tell with this phenomenon,” Buescher says. “Gerrymandering has contributed to the decline in compromise and cooperation, or the decline in compromise and cooperation has encouraged Gerrymandering. Either could be true. Either way, it is unfortunate.”

In 2016, Colorado’s 3.2 million voters were 31 percent Democrat, 31 percent Republican, 37 percent Independent (or what Colorado calls “Unaffiliated”), and the rest “Other”. The state has 35 state senate districts and 65 state house districts — a total of 100 legislators. Federally, of course, Colorado has 2 senators, and has 7 seats in the House.

In the 2016 election in Colorado, the average margin of victory, for the Democrat or the Republican — whoever won — was 23 percent, so none of these races could really be called competitive. Buescher argued that at least six of the seven state seats in the U.S. House of Representatives were “safe” — districts where the opposing party had little or no chance of winning the election due to Gerrymandering. There was a similar situation in the state Assembly: only three of the 65 State Assembly seats were viewed as competitive, and only six of the 35 State Senate seats were competitive.

Both parties love having safe seats: it means they don’t have to really engage in these races; they don’t have to spend money to woo voters. All they have to do is make their party voters happy, which means they’re catering to a distinct minority of voters, no matter which party they’re in: both Democrats and Republicans only represented 31 percent of the voters; the largest block of voters, the 37 percent of Independents, as usual were barely represented in the state legislature or in Congress.

Buescher reached out to fellow Democrats and Republicans, not to mention Independents, to come up with a way to fix the problem.

Their solution was to come up with a 12-person committee to do the redistricting after the census, but the makeup of the committee is only half of the battle: the other half is how they would be chosen.

First, the makeup. This is what got my attention to what Buescher’s group proposed: according to the draft law he and his group came up with, the 12 seats in the committee would consist of four Republicans, four Democrats, and four Independents — none of the three would have the majority of the votes. There was also an explicitly stated goal that each district should promote competition for the seat in question rather than pre-ordain that one party or the other had an advantage — or, the way they put it, “to maximize the number of competitive seats to the extent possible.” They did that by “requiring the commission to draw districts with a focus on communities of interest and political subdivisions, such as cities and counties, … and prohibiting maps from being drawn to dilute the electoral influence of any racial or ethnic group, or to protect any incumbent, any political candidate, or any political party.”

In other words, they chose to embrace actual democracy. What a concept! And isn’t it sad to think how hard we have to work these days to make that happen?!

The group, by the way, consisted of two Democrats, including Buescher, and two Republicans, and all of them he says were former legislators: they didn’t have to worry about re-election. They later brought in a couple of Independents, which was a good idea. One problem the group was struggling with was, “how do you get true Unaffiliated individuals on to the Commissions?” he said. “This was one of the hardest challenges. It was suggested that the Republican members and the Democratic members should choose the Unaffiliated members. But our strongest Unaffiliated member asked us, ‘Why should the Republicans and Democrats get to choose the Unaffiliated, when the Unaffiliated have no say in the Republicans and Democrats on the Commission?’ Point well made,” he said.

Which leads to the second half: the final decision on how the specific members of the committee were to be chosen, and they started with who couldn’t be members. No lobbyists. No federal campaign committee employees. No federal, state, or local elected officials. And here’s where Uncommon Sense really comes in. “We are hoping that ordinary citizens — Unaffiliateds, Republicans, and Democrats — apply for the commissions,” Buescher said. “We hope for many, many applications. The applications will be reviewed to make sure that the individuals are not disqualified” — not elected officials, party officers, or lobbyists.

Then, he continued, “From the pools of Republicans and Democrats, two each are chosen by lot; the other two are chosen by leadership of the Parties. [And] all four Unaffiliateds are chosen by lot.” Randomly, so it’s pretty unlikely that the commission can be stacked with shills — not when eight of the 12 seats on the commission are chosen randomly!

“This is a bit cumbersome,” Buescher admits, but “We have designed this to limit the influence of the parties [because] we suspect that both parties will try to manipulate the process. So, we are going to work to get the maximum number of applicants, especially Unaffiliated voters, so that the integrity of the Commission is protected.”

It’s a brilliant display of Uncommon Sense, isn’t it? And by having Republicans and Democrats and Independents in the group drafting this law, it increased the buy-in from partisans and non-partisans alike. But once they finalized the initiative for the ballot, they hit a snag. The proposal was appealed to the state Supreme Court because Colorado law says initiatives can only cover one issue, and the commission was set up to do redistricting of both the Colorado state legislative districts, and the federal Congressional districts. It might sound like nitpicking, but they used the opportunity to pull the measure back, do some more fine-tuning, and reintroduce two separate measures to amend the Colorado state Constitution: Amendment Y for Congressional redistricting, and Amendment Z for state-level redistricting.

The next step was to get them both on the ballot. There are two paths for that: gathering enough signatures from voters on petitions to force it onto the ballot, or take a vote of state legislators. It would cost about $2 million to go through the petition process, so “We decided to ask the General Assembly, the Legislature, to consider these measures and refer them to the voters,” Buescher said. And? “Leadership of both parties endorsed the measures and agreed to sponsor them. The measures sailed through the Legislature without a single vote in opposition.”

If there was ever a sign that a proposed Constitutional amendment was created fairly and without favor to any political group, that has to be it. “One Political observer,” Buescher said without naming him, “called this effort the most remarkable example of cooperation that he has ever seen in the political world.”

The two measures were on the ballot in 2018. Amendment Y, for the federal Congressional redistricting change, was passed by voters 71.37 percent to 28.63 percent. Amendment Z, for the state redistricting change, passed 71.07 percent to 28.93 percent. As a Colorado resident, I very definitely voted for both of them.

The redistricting maps provided to prior Commissions were drawn by political staffers. Not anymore: the Amendments require them to be drafted by the legislature’s non-partisan staff. Even better is the next requirement. “It has become an expectation of citizens that public bodies — city councils, county commissioners, legislatures — work in public, and that their decisions should be subject to public scrutiny,” Buescher said. “We believe that, as someone once said, ‘Sunshine is the best disinfectant.’” Therefore, “We’ve required open meetings, in some ways even stronger than the rules that apply to the legislature. And all documents and maps will be open records.” Which means: available for public inspection, rather than being secret smoke-filled-room documents.

Now obviously, there’s a lot more detail to the story, and this summary naturally quotes Bernie Buescher quite a lot because it’s based on a talk he gave at TEDx in Grand Junction last weekend, which I attended. I appreciate that he quickly supplied me the text of his speech when I emailed him asking for it the next day. His speech definitely gives credit to a lot of other individuals, and I glossed over all of that since I had direct quotes from him available, and I try to keep these episodes down to about 20 minutes.

Their successful effort was definitely a long process, but probably short in the world of changing the political landscape: after the group of four informally agreed to proceed over lunch, they formally launched their campaign on November 16, 2015. Very quickly others endorsed the idea, including former Colorado governors Dick Lamm, a Democrat, and Bill Owens, a Republican.

“By my count,” Buescher said, “we went through over 85 drafts of the proposals.” Even with the setback of having to withdraw the original final ballot proposal because they needed to rewrite the measures to have two separate amendments, for federal and state districts, they went on the ballot for the November 6, 2018 election — just under three years later — and their strong support by voters have made redistricting in Colorado fundamentally more fair.

And just in time: Colorado’s population growth has been enough in recent years that the 2020 Census, which just started, will almost certainly result in Colorado getting an eighth seat in Congress, which means the federal districts in the state will definitely change quite dramatically.

On Friday, Colorado Public Radio reported that 150 people applied to be on the commissions: Buescher said he “hoped for many, many applications.” That sounds like a great start to me. And by the way, as of February 2020 the Colorado Secretary of State reports that of the nearly 3.5 million active registered voters in the state, 30.2 percent are Democrats, 28.2 percent are Republicans, 39.9 percent are Unaffiliated, and the rest are “Other”. Independents and “Other” are growing, yet the two parties, which are slowly diminishing, still dominate politics. It’s by design, and Gerrymandering is one of the tools they use to keep their power over the majority that are not members of either party.

“I think this is a great story,” Buescher said, “one I hope other states can emulate.” I’m happy to help bring it to your attention, and acknowledge that other states have passed redistricting reform, including Ohio, Michigan, and Missouri, though I haven’t researched them to see how well they did it. If you want your political bodies to be more representative of the actual population in your area, this is something to promote in your state, province, and/or country.

Last, here are Buescher’s several lessons learned:

- Develop the proposals outside the halls of the State Legislature, with representation from retired legislators and unaffiliated voters.

- Unaffiliated voters deserve representation equal to their voting strength.

- Engage both parties if possible, and the key national groups that are working on redistricting and reapportionment.

- Be persistent in keeping everyone engaged in the discussions. Don’t let anyone walk away.

- To be successful, you must have the financial resources to promote the reforms. Good ideas without money are unlikely to succeed.

The Show Page for this episode is thisistrue.com/podcast64, where I have links to a lot of material including the actual amendments’ language, ballot titles and language, a photo of Bernie Buescher, a place to comment, and a place to contribute to help keep the show going without interruption by ads. Even $5 helps.

I’m Randy Cassingham … and I’ll talk at you later.

– – –

Bad link? Broken image? Other problem on this page? Let Me Know, and thanks.

This page is an example of Randy Cassingham’s style of “Thought-Provoking Entertainment”. His This is True is an email newsletter that uses “weird news” as a vehicle to explore the human condition in an entertaining way. If that sounds good, click here to open a subscribe form.

To really support This is True, you’re invited to sign up for a subscription to the much-expanded Premium edition.

The real beginning of this idea was former Rep. Rob Witwer. He called us together and was the first to pitch redistricting reform. He deserves much credit.

—

Witwer, a Republican, served in the Colorado General Assembly 2005-2009. He is known for pushing for legislation to raise graduation standards for Colorado high school students, especially in math and science. Buescher was elected to the Colorado General Assembly in 2004, and served there until he was appointed Secretary of State by the governor in 2009. -rc

It literally brings tears to my eyes to read Bernie Buescher’s (D) comment deflecting credit for initiating this foundational reform to Rob Witwer (R). As Harry S Truman (D) famously remarked, “It is amazing what you can accomplish if you do not care who gets the credit.”

—

Truman was pretty sharp. So’s Buescher. -rc

What an awesome idea!!! As the two “major” parties continue to shrink (and I don’t see any reason for that to change any time soon), this will also make openings for third party or Independent candidates. There’s a couple of people I’ll be sending this to.

What a great start — now the next step in the process is to allocate electors based on the popular vote, not the current winner-take-all approach. I know, that’s a pretty radical view, but it is one that more clearly reflects the view of the citizens of the state.

I wish California would do that, but we seem to like being a one-party state, which as not-a-democrat really saddens me.

As a student I read a book on the states and how well they were governed. When the state’s people could elect the other party to power, quality legislation went up because the incumbents HAD to show a record of accomplishment helping the voters and the state.

I was just talking with one of my daughters yesterday about gerrymandering as an example of the differences between the American system and ours (the health care system, of course, being the other big one we discussed). We find it difficult to understand why the people of a democratic country would consent to have the machinery of democracy under partisan control.

Here both the census (run by the Australian Bureau of Statistics) and elections (run by the Australian Electoral Commission at a federal level and state Electoral Commissions at the state level) are conducted by non-partisan bodies. The redistricting process is outlined here and here. Some points to note:

So the whole process is conducted by non-partisan bodies and takes place in the public eye. In particular, the reasons for the proposed districting must be published and everyone has an opportunity to comment on them and to raise objections.

—

The whole point of the episode is that we don’t consent to have the machinery of democracy under partisan control, and Colorado is showing how we are forcing the machinery of democracy to be non-partisan, and that other states need to also reassert such control. -rc

The UK electoral system is nearly as bad as the US – it’s shocking how many people don’t understand the unfairness of first past the post and the role of gerrymandering in making up our House of Commons.

A great way to explain it is with the Districts game, on Google Play for Android.