We were quite aware of the earthquake and tsunami last week, and naturally a related story made it into True. Let’s start with that.

Slow-Motion Emergency

As a confirmed tsunami sped toward Hawaii after a massive earthquake off Russia, a Norwegian Cruise Line ship Pride of America docked in Hilo cast off its lines and headed out to sea — the safest place for a ship is deep water. The only problem: 600 passengers were ashore, enjoying the island. NCL sent a message to passengers who were ashore about the two-hour-early departure — 18 minutes before the ship left, and hours before the waves were due to arrive. Locals directed the stranded passengers to a shelter. The ship returned the next day to pick them up again. (RC/KHON Honolulu) …Because if there’s anything a smallish community needs in times of disaster, it’s an extra 600 bunks, and 600 extra mouths to feed from the Shame of America.

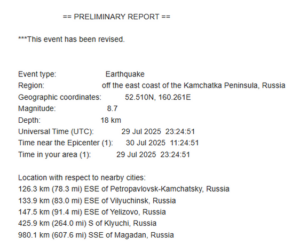

The 8.8-magnitude earthquake struck off Kamchatka at 1:25 p.m., Honolulu time …while we were in the north Pacific. A Tsunami Watch was issued at 1:33 p.m., and was upgraded to a Warning at 2:43 p.m. The NCL ship left port at 4:00 p.m., giving very little warning for those ashore. While it does take a ship a little time to cast off lines and get moving, “deep water” isn’t very far off any of the Hawaiian islands.

What Cruise Ships Must Do

As the story says, ships must head for deep water if there is time! And there was plenty of time.

The rule of thumb for “deep water” is 1,000ish feet, or 300ish meters. When I researched this with ChatGPT, it said that “If under full emergency power and with port authority clearance, a cruise ship might get there in as little as 30 minutes. But more conservatively, 45–60 minutes is realistic for full tsunami safety.” That sounds pretty reasonable (it’s always smart to sanity-check Chatty-G).

The Pacific Tsunami Warning Center — which is located in Honolulu — gave the estimated arrival time for the first wave as 7:17 p.m., or more than three hours after NCL departed. They literally left passengers on the dock, who then had to make their way to higher ground. Those who were on excursions were taken directly to a shelter, rather than to the port.

It’s left unclear how many crew were with the 600 passengers, which is certainly an estimate despite the fact they knew exactly how many passengers and crew were not aboard, as we check out with security every time we leave, and check in again when we get back. They do it by scanning our key cards, which records our arrivals and departures. At any moment, they can query the database for a list of who is off-ship.

Wanna bet it was actually more than 600 total? Not only might it be excursion-related crew, but part of the appeal for cruise ship employees, including housekeepers, waiters, bartenders, and officers, is they get time off to visit some ports, just like the passengers they serve.

Duty to Passengers

In addition to the tardy text message, the ship did a very poor job of communicating with those passengers. “Nobody knows what’s going on,” said “Mandy the Cruise Planner”, a “cruise addict” who documents her cruising adventures on TikTok. She was left behind while other family members on the ship were “terrified for us — we’re terrified for us,” she said. “The kids are just terrified on the ship, and the communication is not great.”

Hawaii News Now documented the ship leaving “chaos at the port” as it pulled out without people waiting to board …more than two hours before waves were due to arrive. It’s very well known that the time of arrival of a tsunami is quite precise to estimate, though its size is not at all easy to estimate. They of course could not return until the emergency was lifted and dock facilities were inspected for damage.

Wave size depends on the intensity of the earthquake, the distance the waves travel, the direction the waves are coming from and, importantly, the underwater geography near the coast. A wave may be barely noticeable in one spot but may be very destructive only a few miles away.

Yes, the NCL ship absolutely should have left. But in my opinion, they were way too hasty about fleeing, and unnecessarily stranded a lot of people, adding a significant burden on local emergency services. NCL should make a significant donation to Hilo disaster agencies to help with that burden. Only then will “Shame of America” be replaced by “Pride of America” in my mind.

You might say that cruise ship captains have a duty to safeguard their ships, and the passengers they have aboard. Indeed they do. Yet True is all about thinking, not reacting. They had plenty of time to gather nearby passengers …if the passengers knew to come back! Yet when they cast off, they had three more hours to get to sea. They could have, and should have, taken the opportunity to recall passengers with at least a half-hour of notice, if not more; not 18 minutes. Why was it delayed so much, eating up valuable time? Well, I’ll discuss that more below.

Where Were We?

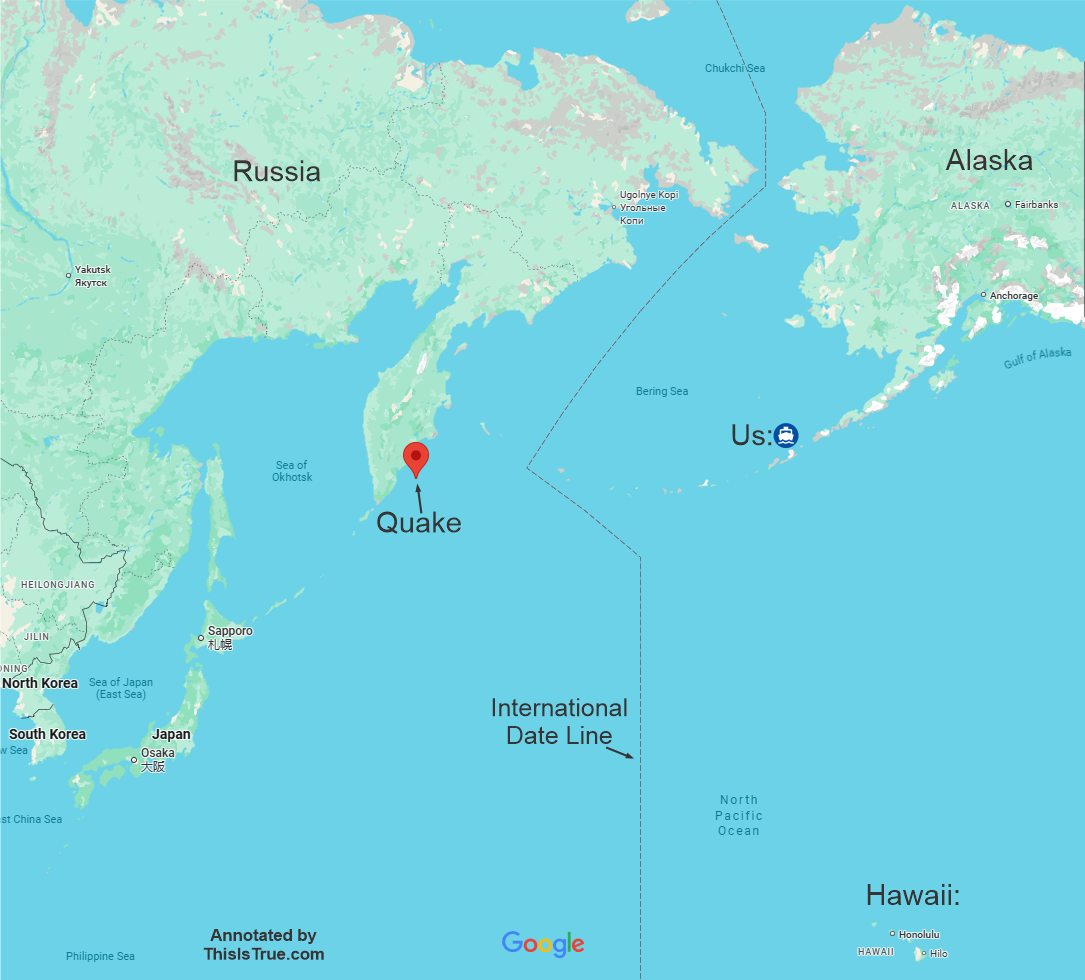

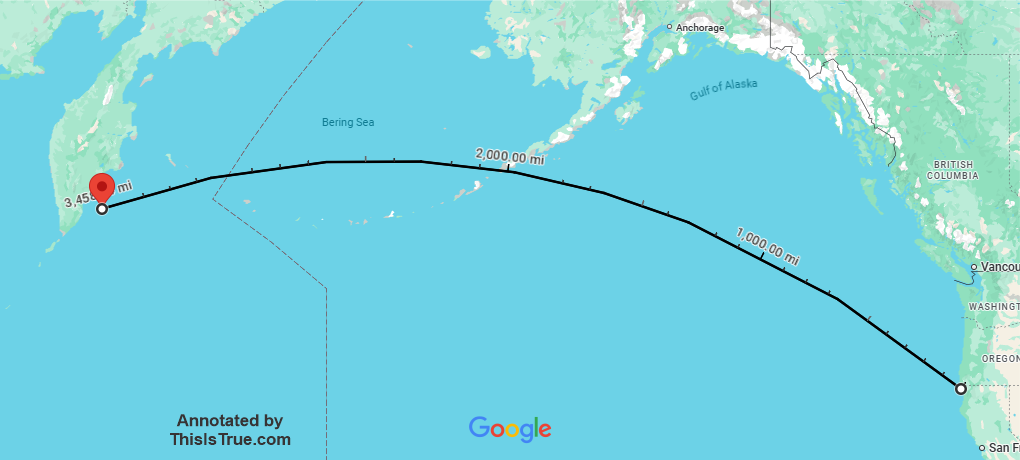

As most of you know by now, my wife and I live full time on the first real Residential Cruising ship, which takes 3- to 3-1/2 years to circumnavigate the globe. What some may have not realized: we were in the north Pacific Ocean at the time of the quake, which happened in the north-west Pacific, just off Russia’s Kamchatka Peninsula — a place known for big quakes and tsunamis.

About 29 hours before the quake, I happened to take this screenshot of our location. Minutes before that, noticing we were passing Unimak island, I popped out to our balcony to get “a last look” at land before our long trek to Japan. Couldn’t see a thing: there was heavy fog — and it’s been that way for most of our trip to Japan. Oh well! But at least this recorded our location for me, with a time stamp.

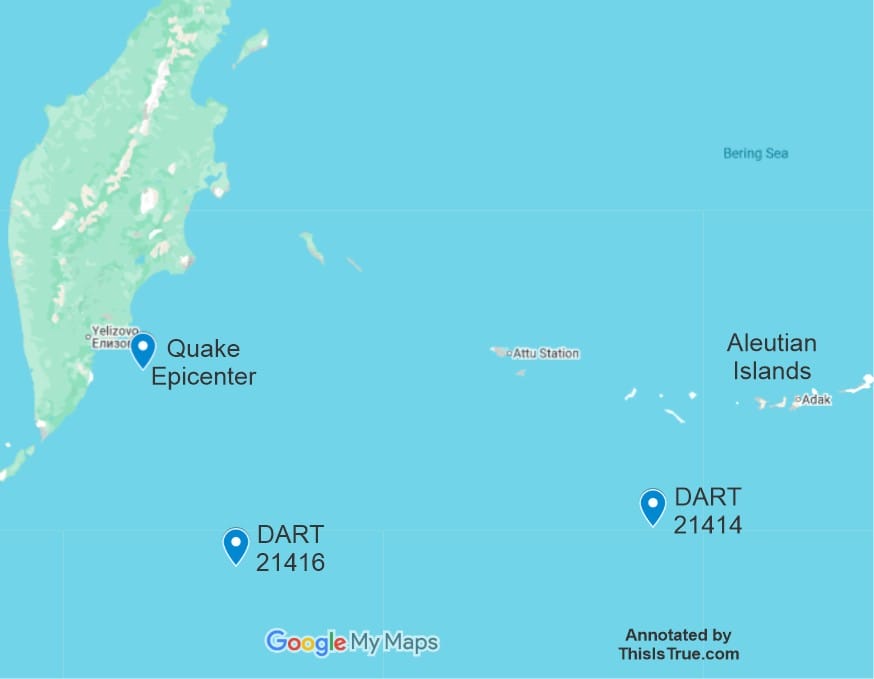

And here was our approximate position at the time of the quake:

Speaking of distances, let’s look at the proximity of Crescent City, Calif. The hardest-hit U.S. location, with around $1 million in damages, is nearly 3,500 miles from the quake:

Why Are Ships Safe at Sea?

First, not all underwater earthquakes cause tsunamis. To start a tsunami, an underwater earthquake must have vertical motion and measure at least 6.5 on the Richter Scale, and it must be centered less than 30 miles under the ocean floor. Large volcanic explosions and underwater landslides can sometimes generate waves.

The key is large water displacement. The Kuril–Kamchatka Trench formed due to a subduction zone — where one tectonic plate converges with another, and the heavier of the two sinks under the other. When there is sudden movement (an earthquake) from pent-up pressure, and it’s underwater (yet not too deep in the crust), there’s vertical displacement of the water, which ripples out from the quake.

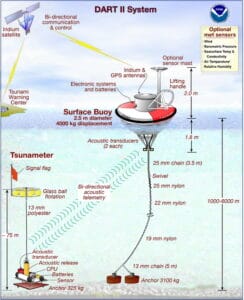

No matter what you saw in the terrible film The Poseidon Adventure, tsunamis are not giant waves in open water. They travel across the open ocean at up to 670 miles per hour, the speed being determined solely by the depth of the water. In open water, the wave cannot be seen or felt by boats, nor does it noticeably rise above sea level until it reaches land. (“Noticeably” is important: sea sensors can detect them — that’s how we know when a tsunami is generated.) That’s why ships in deep water are totally safe: the waves are, in a real sense, only under the surface.

Just like when you drop a pebble in water and multiple rings spread from the impact point, a tsunami is similarly multiple waves. NOAA uses a network of “DART” sensors — Deep-ocean Assessment and Reporting of Tsunamis — that have pressure sensors that lie on the ocean floor, which relays measurements to a buoy above, which then transmits its findings to the Tsunami Warning Center.

In the Tsunami Warning bulletin shown (tall and thin, well above), it notes that DART 21414 measured waves of about 0.28m (0.9 ft) with a period of 32 minutes between the waves. That’s a long, slow, ripple — yet those ripples are moving at more than 600 mph! DART 21416 also picked up the waves, but they were bigger: 0.9m (3.0 ft!) with a period of 24 minutes. A positive reading, and a confirmed reading. That’s how they knew the tsunami existed.

Plus, remember that big quakes typically have aftershocks, and if big enough, can also produce their own waves. I’ve not heard of that happening in this quake, though.

And because we have a reasonably good map of the sea floor — we know the depth of the ocean at least with enough accuracy to know wave speeds — a computer can pretty quickly predict wave arrival at any point in the Pacific. Such as Hawaii. That answer wasn’t “sometime between 7:00 and 7:30 p.m.” but rather precisely at 7:17 p.m.

It’s not until a tsunami reaches shallower water and approaches land that its speed drops. In 60 feet of water, speed goes down to about 30 mph. But when the speed drops, the faster water behind builds up, and the wave rises in height. By the time it crests at a beach, the wave can be many feet high.

Back when I was in college, I interviewed Mark Spaeth, then the Tsunami Program Director of the National Weather Service, and one of the nation’s leading experts on tsunamis. He told me that the first wave usually isn’t the largest, though marine scientists are not sure exactly why. And the third and fourth waves sometimes are even bigger than the second. “I’ve seen records where the maximum wave might have occurred 24 hours after the first,” he said.

That’s why the active phase of the disaster is hours and hours long, sometimes all day. That’s why a ship can’t return after “the wave” has hit, because there’s almost certainly going to be multiple waves, separated by hours.

First Reports

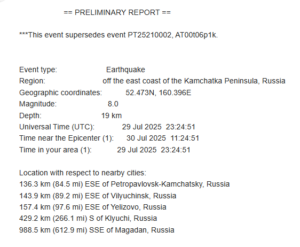

I happened to have been at my desk when all this unfolded. I get quick reports of major earthquakes: when I worked at NASA/JPL, I knew a gal who worked at the Seismological Laboratory at Caltech, and she told me how to sign up for those reports. I’ve been getting them for more than 30 years now.

And when I got the first report, inserted above, it showed the quake was an 8.0. An 8.8 is much larger — why the “mistake”? I later got an update, as shown here.

When there’s an earthquake, preliminary automated systems issue an initial magnitude within minutes — based on limited data. The alerts go out quickly by email (and probably other means; I’m on the email distribution). As more seismic stations report, more sophisticated waveform modeling kicks in, and the magnitude is revised. An updated email goes out.

In this case, that update showed an increase to 8.7. Then seismologists review the data, and probably get more detail from other seismic stations. In this case, the magnitude settled on 8.8.

Unimak Island

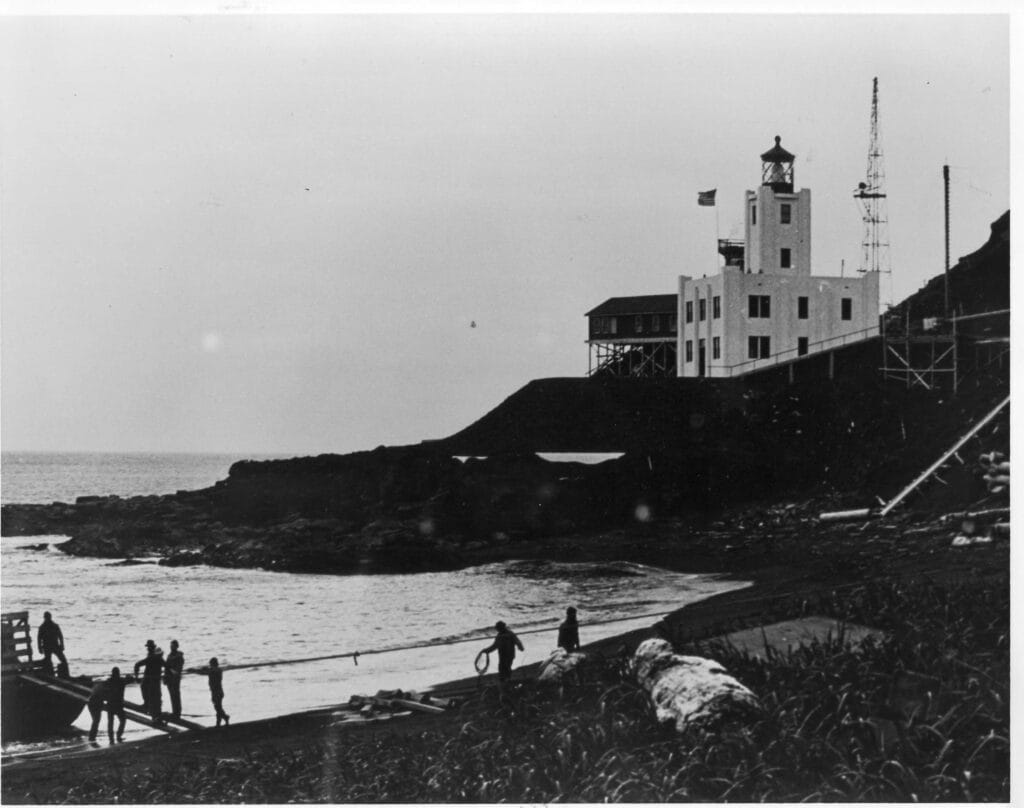

To give you a little idea of the destructive power of a tsunami, consider Unimak Island, the little spot we cut through to get into the Bering Sea, which is part of the North Pacific. In 1940, the U.S. Coast Guard rebuilt the lighthouse on the southwest corner of the island. I would have been able to see it if it hadn’t been so foggy:

As you can see, it was built up on a hill, the preferred place for lighthouses, and the construction is pretty darned solid. Why is it so big for a tiny, rural spot? Because even with the lighthouse (the first one was built in that spot in 1903), there were often shipwrecks nearby, and the survivors would make their way to the house for safety. For instance, in 1942, the Russian freighter Turksib wrecked near the station. The 60 survivors lived at the station for several weeks because rough seas prevented a rescue ship from reaching the station.

On April 1, 1946, a nearby magnitude 8.6 earthquake generated a tsunami. This is what the lighthouse looked like afterward:

All five of the lighthouse crew were killed.

Four and a half hours later, waves started to hit Hawaii:

Despite the 4.5-hour delay, there was no warning for Hawaii, and 159 people were killed, and many more injured. It’s because of that delay that scientists realized that there could be a network of seismographs and ocean sensors built to provide plenty of warning for areas that could be in grave danger.

That system was built. It’s what provided warnings for Hawaii, Crescent City, and other affected areas last week.

All of This — the technology, the system set up to give fast warnings that waves are on the way, and when they’ll arrive, and more — that is the real “Pride of America”, figuring it all out and putting it together to prevent the tragic loss of life. NCL needs to make things right for Hilo for adding to their emergency.

Addendum: the Real Issue is Communications

Every time — every single time! — I’ve been involved in a big emergency incident, the After Action analysis points to failures in communications as a contributing factor to the chaos.

And I’ve seen it time and time again in big incidents I’ve read about, such as the Columbine School Shooting. Whether it’s the radio system being overloaded, different responders from different agencies not having common communications systems to be able to talk with each other, or simply having someone (or in truly large incidents, several someones) assigned the responsibility to communicate what’s going on to the first responders involved, and/or the public at large.

The Tsunami Warning System is very well set up: it did its job of communicating what was going on, what was at stake, when it was going to happen, and delivering that message to those who needed to hear it, such as Emergency Managers in every coastal area at risk.

That’s fairly easy; the feds just say “Here’s how we will tell you” and it’s up to local officials to monitor that channel.

The hard part is, “then what?”

But even small- and medium-sized companies need to have emergency plans in place, and a means to communicate from there. I speak here especially of Norwegian Cruise Lines.

It’s actually a positive sign that — even if delayed — they could send a “text message” to passengers who were ashore. It’s unclear whether that message was sent through the NCL app, which I had on my phone when Kit and I traveled on an NCL ship when we crossed the Atlantic in 2024, or if they had a system to gather passenger cell phone numbers and a mechanism for sending SMS text messages.

The Key: Having a Plan

I worked with our county’s Emergency Manager for nearly 20 years, with two different people in that role. My specialty with them was radio communications, but I was very aware that their primary responsibility was to have a bookshelf full of detailed, written plans for multiple scenarios.

What if a wildfire is threatening a populated part of the county? There was a plan for that. It wasn’t just that it was on the bookshelf, but that everything was thought through about what to do. One obvious thing: there had to be a way to communicate the danger to the public, and tell them clearly what to do to save their lives.

That meant the county had to budget for, procure, and set up a system for sending (yes!) voice and text messages to residents, as well as a way to choose which landline and cell numbers to call. That’s not an easy task: a visitor from out of the state could be in that danger area, and probably didn’t provide their number to a “list” for emergency messages. There are ways to alert them, hence the need for a budget and service procurement to do it, and it needs to be set up ahead of time, and tested periodically.

And that’s just one of many possible disaster scenarios.

Back to Cruise Ships — Ours

Since I’m a “scenario planning” sort to begin with, I long ago considered the “what if?” of a tsunami during our long ship voyage. I already knew there is no problem for us when in deep water, but what if a tsunami hit a port we were heading for, causing significant damage? We might not be able to go there to see it and, worse, we might not be able to get supplies, fuel, and more.

And “what if” we are already in port? Hopefully the ship would have time to head to deep water to escape danger. Yet indeed, anytime we’re in port, some portion of the Residents are likely to be ashore, exploring. It’s part of why we’re there.

NCL at least had an app, and it was handy that they were in the U.S., and most cruise ship passengers are from the U.S.; the same is true on our ship. But we have no smartphone app. They do have a list of all of our cell numbers, but probably no system to text us in bulk.

Residents haven’t just shrugged: we have a loose communications system among ourselves. It’s not just that most of us have several friends in our phonebooks so we can text them, though that helps …a little. We also have groups set up on WhatsApp where we can reach many shipmates.

The problem is, that’s not official, and not everyone is on it, including no ship personnel. And even if everyone was on it, often those groups’ notifications are silenced because there’s too much chatter on them, and none of us want to be bothered by constant alerts.

The bottom line is, neither the company, nor the ship’s captain, has any way to quickly reach “most” of us, let alone all of us, in an emergency when we’re not onboard. Worse, we don’t have a reliable way to call the ship, either. We have to resort to calling the numbers we have for other Residents, hoping they’re on the ship and can (and will) pass a message to someone who will act on it. (The official way to contact the ship is to email the Service Desk, which is manned 24×7.)

Destructive tsunamis can be years apart …or days apart. We never know when there will be a big quake. Two tsunamis were generated, threatening Alaska, while we were in the state. The first one was on July 16, a 7.3 quake near Sand Point, Alaska, which generated a small tsunami that resulted in evacuations from Homer, Alaska …5 days before we arrived. Luckily, those waves were inches high, not feet high. I paid close attention to that one, too.

Consider it a wakeup call. If we (and by that I mean all cruise ships, Residential or otherwise) didn’t hear the first wakeup alert, we had better have heard the second, and done something about it, before the next one hits.

August 7 Update

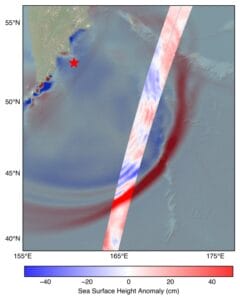

This Just In: My former colleagues at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory report that the SWOT (Surface Water and Ocean Topography) satellite, a joint effort between NASA and the French space agency, captured the tsunami about 70 minutes after it was generated. The data was turned into the map/chart shown here.

The measurements included a wave height exceeding 45cm (1.5 ft) in open ocean. Considering we were in swells of 1-2m (3-6 ft), there was virtually no chance that we would have noticed that zooming by, even if we knew exactly when it was coming and where to look. It’s possible that we might have felt it …among the scores to hundreds of other bumps that we normally feel over the course of an hour.

Here’s the key: “A 1.5-foot-tall wave might not seem like much, but tsunamis are waves that extend from the seafloor to the ocean’s surface,” said Ben Hamlington, a JPL oceanographer. “What might only be a foot or two in the open ocean can become a 30-foot wave in shallower water at the coast.”

So why does this satellite data matter? The tsunami measurements SWOT collected are helping scientists at NOAA’s Center for Tsunami Research improve their tsunami forecast model. Based on outputs from that model, NOAA sends out alerts to coastal communities potentially in the path of a tsunami. The model uses a set of earthquake-tsunami scenarios based on past observations, as well as real-time observations from sensors in the ocean.

The SWOT data on the height, shape, and direction of the tsunami wave is key to improving these types of forecast models. “The satellite observations help researchers to better reverse engineer the cause of a tsunami, and in this case, they also showed us that NOAA’s tsunami forecast was right on the money,” said Josh Willis, another JPL oceanographer.

The NOAA Center for Tsunami Research tested their model with SWOT’s tsunami data, and the results were exciting, said Vasily Titov, the center’s chief scientist in Seattle. “It suggests SWOT data could significantly enhance operational tsunami forecasts — a capability sought since the 2004 Sumatra event” — the tsunami generated by that devastating quake killed thousands of people and caused widespread damage in Indonesia.

For more about the satellite, see JPL’s SWOT subsite. It was launched in December 2022, and is 2 years, 7-1/2 months into its planned 3-year life.

– – –

Bad link? Broken image? Other problem on this page? Use the Help button lower right, and thanks.

This page is an example of my style of “Thought-Provoking Entertainment”. This is True is an email newsletter that uses “weird news” as a vehicle to explore the human condition in an entertaining way. If that sounds good, click here to open a subscribe form.

To really support This is True, you’re invited to sign up for a subscription to the much-expanded “Premium” edition:

Q: Why would I want to pay more than the minimum rate?

A: To support the publication to help it thrive and stay online: this kind of support means less future need for price increases (and smaller increases when they do happen), which enables more people to upgrade. This option was requested by existing Premium subscribers.

I hope Villa Vie comes up with an emergency notification system ASAP, and pretty sure you are already working on getting it done 🙂

—

Starting with giving a pre-publication copy of this page to an appropriate officer. -rc

Great report Randy. Lots of good, useful and interesting information on tsunamis.

It’s odd, when I started reading this I thought it was a well considered but very pointed challenge to an old nemesis of yours. But the last paragraphs must be disconcerting to you and your fellow residents.

Can I assume that you’ll be raising this with the ship’s crew/managers/captain? I know I would, a broadcast app isn’t that difficult to achieve and must have additional benefits to the ship.

We’re regular cruisers too and I’ll definitely be checking that they have broadcast comms capability going forward.

—

See my reply to the first comment (which wasn’t published yet when you wrote this). 🙂

As for NCL, I wouldn’t say they’re a nemesis: we had a great time with them on a 2014 cruise to Alaska. They have gone downhill significantly since, including the incident you are thinking of. -rc

Two missing things. How far offshore is safe? 1 mile, 10 miles, 100 miles? I noticed right off the coast here in Southern California the ships waiting to enter the port of Long Beach were not booking it for open water.

This goes to the NCL. If they only had to go say 1-2 miles out of the port what could that possibly take a half hour at most to push back and reach safe water?

We saw the beaches cleared, 6 hours before they were to arrive. Piers closed, and aggressive police closures of parking areas along coastal areas. This is not the first time this was done for a non-event. The science was clear, the results elsewhere were clear this was a non-event. The science was clear, and was not trusted. Oh it COULD happen. We were told to trust the science right? Why not with this event?

It’s feeling more and more that we are heading to a boy who cried wolf situation. We have had false alarm after false alarm. Hurricanes have been the same way. How many more non-events before people ignore all future warnings? Is there anything else we should be doing like being way more conservative with these warnings?

—

I thought I was reasonably clear: distance offshore isn’t the key, the depth of the water is, and that varies wildly with offshore geography, which is why I pointed out that “’deep water’ isn’t very far off any of the Hawaiian islands” — it ramps down very quickly. In other places a ship might need to go more than a mile to get into 300m of water. That said, one mile offshore is probably not enough for a different reason than waves: if it’s a hugely destructive tsunami, when it recedes between waves, it drags an awful lot of debris out to sea (and, sadly, bodies, not necessarily dead). They don’t want to be in that debris field.

Also sadly, your attitude is what kills people. As I also made reasonably clear, they don’t know how bad the waves will be. “Wave size depends on the intensity of the earthquake, the distance the waves travel, the direction the waves are coming from and, importantly, the underwater geography near the coast. A wave may be barely noticeable in one spot but may be very destructive only a few miles away.” IT DOES NOT MATTER that “the results elsewhere were clear”; it was a “non-event” there. While it might seem extreme to evacuate beaches 6 hours before, how long do you want them to wait? How long will it take to evacuate the beach? Depends on how many people there are, eh? And what do god-damned obliviots do when they hear the warnings? They flock to the beach “to watch.”

I recommend you read this entire page again with curiosity and a desire to learn, and grasp just how big of a problem this is. Just like with hurricanes, you can’t wait until the last minute to say, “Oh shit, it’s bearing down for a direct hit on the city, I guess we had better start evacuations!” — and it’s frankly ridiculous to not grasp this: it’s why people die when it IS a big one. THINK! -rc

I’m not sure I agree with your criticism of NCL. Since DOGE has managed to disrupt and eliminate many positions in the NWS (as well as other departments that we rely on) it may have caused some reservations about the timing that the Tsunami Warning Center gave for its arrival. Consider the disaster if the ship had still been there loading passengers when it arrived.

—

The NWS/NOAA lost around 600 of its staff in DOGE cuts, including some at the Tsunami Warning Center. But NWS has already been working to replace many critical personnel. While we don’t have insight as to the staffing impact at the TWC, one thing that’s done almost entirely by software is the wave propagation from a confirmed tsunami. The warning was issued, as shown above, and it had the exact arrival time, as it always has. And no one is unsure about accuracy: that was tested quite well in the June 16 event described at the end. There is no way for waves to suddenly travel twice as fast; “up to 670 miles per hour” is already astounding. -rc

Great info!

As a sciencey type (not a scientist) that is interested in natural phenomena I looked up some info about this and other big quakes in terms of the equivalent energy released in kilotons (kt).

The 8.8 quake near Kamchatka was about 16,000,000 kt and the 2011 9.0 Tohoku quake was about 32,000,000 kt. The 2004 9.25 Sumatra quake was about 63,000,000 kt.

Lastly, the Chicxulub asteroid hit was about 100,000,000,000 kt which is a HUNDRED 10 mag quakes!

—

This is interesting, but needs work: kt is not a measure of energy — kilotons …of what? It’s most likely you mean “equivalent of TNT”. The measure of energy “should” be Joules. Using the USGS magnitude–energy formula, a M 8.8 quake would generate about 1×10^18 J, which is roughly the equivalent of 239,005 kt of TNT, aka a bit over 239 million tons.

USGS has a great online calculator to show the differences of energy output by quake size. I put in the two quakes discussed here (M7.3 and 8.8), and it shows the latter is 31.622 times “bigger”, which equates to 177.827 times stronger in the sense of energy output.

To find the energy output for a quake, the Omni Calculator site provides that, and shows that the 8.8 quake is the equivalent to 15,939 of the atomic bombs dropped onto Hiroshima. We’re talking a LOT of energy!

These energy numbers show how the tsunamis varied widely for the 3 quakes. And what it must have been like when the asteroid hit. -rc

While I totally agree on the communication issues with NCL, I disagree a bit on the ship leaving when it did. That Captain is responsible for getting that ship to safe waters. While yes it might only be 30 minutes out, how many other vessels are trying to make that same journey. And how many of the other vessels are going to stop and wait at that minimal safe point.

A tsunami is not an event that you want to be near other vessels. What if the only harbor channel becomes fouled by one of the other vessels trying to leave? Waiting to the last minute could be disastrous for the ship. In the Navy our carrier was three hours late leaving Tarragona Spain. Another commercial vessel had become disabled in the only channel that the carrier could use. Also the ship has to abide by the harbor master. If a vessel is told to leave the pier as soon as possible, this is not something the ships Captain can just ignore. A cruise ship can pull lines and exit the harbor quicker than bulk carriers, so I would think the harbor master would want to get it out the way of other large vessels that would need assistance, and take longer in exciting to safe water.

I will not second guess the ships Captain for leaving when he did. There are many more aspects than appear obvious at first glance. I will agree that NCLs communication was terrible.

—

Fair points. -rc

Very informative and definitely something for you guys to get a plan together for. You can have an emergency WhatsApp group set up with everyone who wishes to participate and have alerts from it always set to on and the loudest. Then it is only used for extreme emergencies. Just a suggestion.

—

The problem: MANY refuse to have Meta products installed on their phones due to the incessant tracking. My suggestion to the company, in order of preference: their own app with communication ability, a lightweight app from a service designed for this specific sort of notification, a Telegram group, a Signal group. Apps take awhile, but a Telegram group can be implemented within the day; getting Residents to add the app (if they don’t already have it) and communicating the purpose will take longer. I put Telegram above Signal since it’s used by more people, and is particularly friendly to groups. -rc

Nicely done. You — not NCL.

Fascinating. I do hope you can get the emergency communication sorted ASAP.

—

It was my specialty in my county’s Emergency Management department, but all I can do here is make unsolicited recommendations…. -rc

I was on the Bus with Mandy. The NCL sponsored excursion continued for 90 minutes after the first watch was issued. Several people throughout that critical 90 minutes asked the bus driver if he had any communication with NCL. The answer was a definite NO. We were all worried but couldn’t stop the bus.

Several people received bad information from NCL like they were waiting for us and to get back by 4pm. The bus arrived by 3:50pm. We exited the bus to no avail. The ship was leaving.

I did not receive a single text from NCL even though they had my contact information. In truth, it didn’t matter if the entire bus had been notified by messages from NCL during that critical 90 minutes because we had no legal authority to stop the bus and turn it around.

After reaching Volcano National Park, it was the screaming park authorities who said to get back to the bus and to the ship. I don’t blame the bus driver. His responsibility was to drive. It was the responsibility of NCL to communicate with the USCG and then promptly communicate with Polynesian Adventure Tours to return the buses.

If NCL had promptly communicated, we would have been back to the ship at 2:30pm. That’s 1 full hour before the ship departed. It’s common sense that the ship had to leave, but to those of us who were left terrified, there was lapse of any proactive or proper communication for 90 minutes after the 1:33pm tsunami alert, and 30 minutes after the Watch was issued.

The Hawaiian locals should be praised as heroes and the most beautiful people, even under duress. They opened the high school to us. They gave us water. They gave us snacks. They gave us blankets. They provided us with security throughout the night. They provided us with food. Thank God the islands and locals were safe. NCL should be thankful nothing worse happened because they unnecessarily left us stranded without proper communication.

—

I’m glad to be starting to hear from passengers with their stories. More are welcome to post. -rc

I was in Ketchikan Alaska which is in the Northwest Passage headed up to Juneau on Good Friday 1964. The quake was near Anchorage and is said to be a 9.2 magnitude, second largest recorded. The next day we went down to watch the tsunami — we were probably 100 to 150 feet above the shoreline — but because the island was not directly exposed we saw only a rising of sea level — maybe ten or fifteen feet — which then settled. Damaged a lot of shoreline boats and equipment but never felt dangerous (to a bunch of 19 yo’s!).

While there I had sent my mother an Easter card which she received a few days later and then panicked not knowing if I was impacted. No cell phones in 1964!

I enjoy your writing.

—

There probably wasn’t much of the tsunami left circulating by the next day. (I looked it up: the quake was at 17:36:16 AKST.) -rc