The first most people in the world heard of paramedics was “Johnny and Roy” (Randolph Mantooth and Kevin Tighe) — the lead medics in the Emergency! TV series (NBC, 1972-1977) based on the real life exploits of the Los Angeles County Fire Dept., which was one of the early pioneers in modern Emergency Medical Services.

But they weren’t the first.

Military corpsmen go way back, providing special care to soldiers on the battlefield. Hospitals often provided horse-drawn ambulances, staffed by doctors. And funeral directors’ hearses doubled as medical transport vehicles into the 1950s and 60s, thanks to their cushy ride.

Some areas, notably Toronto, Ont., Canada, pushed for better cardiac emergency field care. There, Medic One was a single ambulance that had a “portable” defibrillator for cardiac calls. The machine was operated by a hospital intern, and it meant bringing the patient to the ambulance, since the defibrillator was powered by lead-acid car batteries — it weighed 100 pounds.

But what about true paramedicine for civilians — comprehensive emergency care from trauma to childbirth to medical emergencies including, yes, cardiac incidents? Where and when did it start, and how? The location was unlikely: Pittsburgh, Pa. And you probably haven’t heard of the very first squad of paramedics, since the squad — even its history — was deliberately buried.

Putting Together the Pieces

In the mid-1960s, Pittsburgh’s United Negro Protest Committee created Freedom House Enterprises Inc. to serve the Hill area of the city. One of their missions was to help build job opportunities for the so-called “unemployable” locals in a time of unrest. The Vietnam War was raging, and there was angst in the streets over the war, civil rights, and more.

Meanwhile at the time, ambulances in the city, like in many cities, were operated by the police department: a “scoop and scoot” service that used essentially untrained officers to give the sick and injured a ride to the hospital.

The vision to change things wasn’t the effort of a single person. Freedom House would be the focal point, and would recruit the staff. The money came from Phillip Hallen, president of the now-defunct Maurice Falk Medical Foundation, and a former ambulance driver. The medicine came from Dr. Peter Safar, the Director of Anesthesiology at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, who was considered the “Father of CPR.” (Safar, by the way, had also invented another level of care: the hospital Intensive Care Unit, in 1950.) And the glue to put the two together was Morton Coleman, of Pitt’s Graduate School of Social Work, who suggested combining an ambulance service with a program to train men (and, during the life of the service, at least two women) not just as ambulance drivers, but as professional emergency medical care providers.

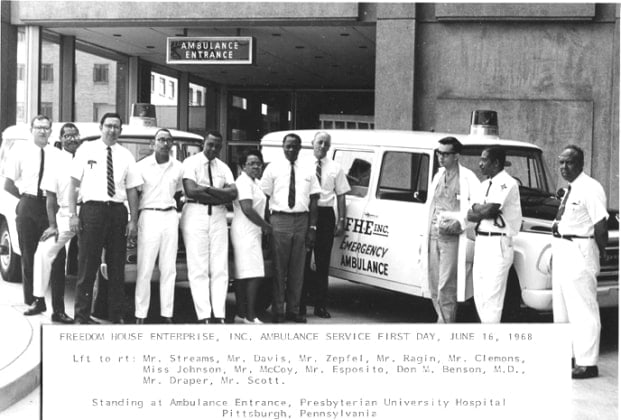

In 1967, the Freedom House Ambulance Service was formed; about 44 men were recruited for training, organized by Dr. Safar. The men were paid a small wage, and in return were expected to attend classes eight hours per day, five days per week, for nine months to learn not just the basics of emergency medical care, but get in depth.

After class, they observed in the emergency room, or did rotations in various hospital departments. And, of course, they learned the latest in CPR as Dr. Safar did his research at the hospital, and later at the institute he founded, the International Resuscitation Research Center (now the University of Pittsburgh Safar Center for Resuscitation Research).

For Dr. Safar, all of this was personal: the year before, in 1966, his own 12-year-old daughter had died from an asthma attack.

Inventing Prehospital Care

There was no such thing as an emergency medical technician, the lowest level of ambulance medic, let alone a paramedic, who provides Advanced Life Support interventions, so Dr. Safar went about inventing much of what we do today. He designed the layout of the ambulances (and their layout today is still based on his drawings), going away from the “ride in the meat wagon” design to a mobile intensive care unit that enabled the medics to provide care to patients en route to the hospital.

To train the staff in CPR, Dr. Safar called upon a doll maker in Norway, Asmund Laerdal, to design and manufacture mannequins for CPR training; Resusci Anne was born. The face of the doll was modeled on the death mask of an unidentified young woman who drowned in the Seine River in the late 1880s. Her gentle smile was perfect — and no doubt reminded Dr. Safar of his own daughter. (Laerdal’s company still exists, and still makes the training dolls today).

Safar, who was Austrian, left no room for racism. When hospital nurses demanded the students get out of delivery rooms, he quickly showed up and ordered them to accept the students — and teach them the ropes.

About 25 of the students made it all the way through training, and they hit the streets in 1968, operating out of Pittsburgh’s Presbyterian and Mercy Hospitals. Their pay: $42 per week.

The police department was happy to turn over the job of ambulance services in the “black areas” of town — the Hill and half of an adjoining precinct in the city, North Oakland. Residents were happy to have their “own kind” provide help, and thanks to the training they had received — and their advanced equipment, including more-portable defibrillators, purchased by the Falk Foundation — the crews very quickly started to save lives. They managed airways, started IVs, delivered babies, and interpreted EKGs.

They were the first paramedics.

But training didn’t end when they hit the streets: in addition to bringing on more and more medics, current medics were continually trained in new skills, and refreshed on everything, a practice that continues today.

These first street paramedics didn’t care whether their patients were black or white or other: they were just there to do a job. The respect didn’t always go both ways: they reported that patients or families would sometimes spit in their faces; they just “kept smiling” and did their jobs the best they could.

Before long, when people called for an ambulance in Pittsburgh, they started asking for the “Freedom Boys” rather than the police meat wagons. You didn’t have to be a doctor to see the difference in care between untrained “ambulance drivers” and highly trained prehospital care professionals.

Documenting it All

When a new, young, female doctor came to Presbyterian hospital in 1973 for her residency, Dr. Safar suggested she might want to work with the Freedom House to help train the street medics.

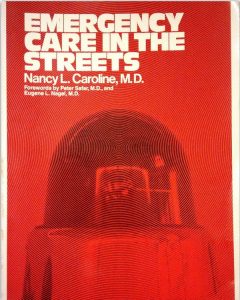

The doctor was Nancy Caroline, who not only worked with the paramedics but also served as their medical director. And she documented the training they received, publishing it all in a book. The result, Emergency Care in the Streets, was literally the textbook to train new paramedics for a decade (but don’t worry: new editions came out frequently).

Caroline became known as “The Mother of Paramedicine” — and she learned it all at Freedom House. (Dr. Caroline died from multiple myeloma in 2002, at 58.)

Successful? We Better Kill It

Despite the program’s enormous success and lives saved, it was not to last. Pittsburgh’s longtime mayor Joe Barr was an enthusiastic supporter of the service, but a new mayor, Pete Flaherty, was elected in 1970. Flaherty claimed that citizens complained that the sirens on the Freedom House ambulances bothered them, so he ordered that they not use the sirens when downtown.

Over time, it became clear that “the negroes” had great ambulance service staffed with paramedics, but everyone else in town had terrible throw-and-go ambulance service from the police. Freedom House offered to expand and offer service city-wide, but the city decided to take over EMS. Flaherty ran on a platform of “deprivatizing” and controlling all services, which he claimed would “cut costs.”

New medics were trained — and all were white. Freedom House medics were allowed to apply for jobs too, but despite promises to respect their certifications, they were later told their pioneering training was not valid: they had to take classes and tests to prove their knowledge. By then, a “substantial number” of Freedom House medics had earned their bachelor’s degrees, and a few even had master’s degrees; three were in pre-med.

Yet somehow, most of these street-experienced medics who had been doing the job for years failed the tests, while brand-new medics trained by the city had no trouble passing their tests. The city literally took the ambulances and all equipment from Freedom House, which ran its last call on October 15, 1975, after about 45,000 emergency responses. Freedom House’s dispatchers, who had also been promised jobs, were also turned away.

Freedom House’s building was torn down, files were lost, and history was forgotten, until….

Documenting the Past

When Gene Starzenski got out of the Marines in 1970, he went home to Pittsburgh, where he worked as an emergency room orderly, and later an ER technician. He wanted to do more, and the only paramedic program available locally was at Freedom House. He applied, but there were no openings.

He moved to California, and in 1975 was certified as the 972nd paramedic in Los Angeles County. Due to his location, Starzenski ended up working for film studios as a paramedic on TV and movie sets. After retiring, he wanted to learn more about the history of his profession, and was shocked that Freedom House was never mentioned. Yet he knew they had been pioneers: he had seen them while working in Pittsburgh emergency rooms.

With the original Freedom House paramedics growing older and starting to die off, Starzenski had to work fast. He filmed interviews with many of the original Freedom House paramedics, as well as Dr. Safar (who died shortly after being interviewed, in 2003).

By then, Nancy Caroline was already dead, but others spoke for her, praising how she worked long hours on the ambulances, and even when she went home, she made herself available for consultation day and night.

In 2009, Starzenski completed a documentary, Freedom House: Street Saviors, to tell the story.

Quick Review

Starzenski showed his documentary at the Colorado State EMS Conference in Keystone, Colo., which I attended, and he brought along two of the original Freedom House paramedics to answer questions. They got a warm and enthusiastic response, even though few in the room had ever heard of Freedom House.

Starzenski is a now-retired studio medic, not a professional film director. Sometimes the film’s background music drowned out the interviews, and (for instance) text crawls along the bottom were so small and blurry they were difficult to read. But the compelling story overcame those technical failures: it’s amazing to see where some of the big names in emergency medicine, from Dr. Safar to Dr. Caroline to Laerdal, intersected with the street to produce a spectacular result — and how overt racism nearly destroyed the legacy they helped create.

“Young people look at athletes with $30 million contracts as their heroes, but athletes and actors are not the real heroes,” Starzenski said. “The people at Freedom House weren’t in it for the money. They wanted to help others. They are the real heroes.” And like a lot of real heroes, they were almost forgotten.

(Story continues after documentary trailer.)

The Documentary, Essentially, Also Failed

Whether the result of continued racism or, more likely, technical issues and money, Starzenski’s documentary has never found a distributor. In the years since, it has only been shown at a few film festivals and EMS conferences. Starzenski won’t release it on the Internet, since then it will be pirated and he’ll have no chance of getting distribution or recover his investment to make the film. That is a horrible shame: the story needs to get out to a wider audience. The record needs to be corrected.

It was a true honor to meet the two representatives from the original paramedic squad — the pioneers who did the work to create a true profession in prehospital care, only to be forgotten.

George McCary III was the first we got to meet. After he was discarded by the city, he became a taxi driver — some irony! “I didn’t realize we were making history,” he told a reporter for the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. “I had a job to do, so I just focused on doing my job.”

Walter Brown Jr. was the other Freedom House pioneer who attended the screening in Colorado, despite feeling ill from Keystone’s 10,000-ft elevation. He remains bitter about being discarded, but declined to tell stories about that because “Peter [Starzenski] doesn’t like controversy as much as I do.” He did, however, tell me that “I had more fun in Vietnam,” where he served before he returned home and joined Freedom House.

In August, the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration — which long-time medics know as the agency that codified prehospital medical training in the United States starting in the 1970s — honored Freedom House for their ground-breaking ambulance service with the agency’s Public Service Award.

“Starting in Presbyterian and Mercy hospitals in 1968, they became the first paramedics in the United States,” the agency said on their web site, “and a bold initiative was born, funded in part through a grant from [the U.S. Department of Transportation].” [Edit: “Said” is appropriate, as the page was later removed from the government web site; the link goes to the Internet Archive.]

The NHTSA also noted that “after the 1968 assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., in Memphis, the Freedom House paramedics were the only emergency medical resources in Pittsburgh willing to respond to calls resulting from riots that broke out in the city.”

“Those men and women,” they said, “faced many challenges, but we have all benefited from their participation as pioneers in the field of EMS. Their contribution went beyond the streets of Pittsburgh when Freedom House field-tested the first ever standard paramedic curriculum that the Department of Transportation published in 1977.” (emphasis added)

“With the NHTSA Public Service Award to the Freedom House Ambulance Service, we reaffirm our acknowledgement of those pioneering members of Freedom House Ambulance Service — as well as its staff and supporters — for their significant contributions to emergency medical services education.”

The Future

The documentary has had some success, though, since it’s quite inspiring. Freedom House has a new life: in 2010 the city of St. Paul, Minn., created an EMS Academy in an old firehouse — and named it Freedom House in honor of Pittsburgh’s pioneering program.

They also renumbered the fire department building “Station 51” after the Emergency! TV show’s station, a nod to the Jack Webb-created TV show that brought the idea to the world.

If you get a chance to see the documentary, do whatever it takes to see it. Meanwhile, you now know how the modern era of emergency medical services really got started.

Related:

- The documentary’s web site

- On this blog: Randolph Mantooth: Still Active in EMS — the TV star is still tirelessly promoting emergency care.

– – –

Bad link? Broken image? Other problem on this page? Let Me Know, and thanks.

This page is an example of Randy Cassingham’s style of “Thought-Provoking Entertainment”. His This is True is an email newsletter that uses “weird news” as a vehicle to explore the human condition in an entertaining way. If that sounds good, click here to open a subscribe form.

To really support This is True, you’re invited to sign up for a subscription to the much-expanded Premium edition.

WOW! What a great story! Such role models! And to think in the City of (and during) Roberto Clemente’s time such overt racism was not only prevalent, but allowed to flourish. And we complain about our local turf wars. I can’t wait to see this.

—

For the young’uns out there, Roberto Clemente was a black professional baseball player for the Pittsburgh Pirates from 1955 until his death in 1972, when he was killed in a plane crash while en route to deliver aid to earthquake victims in Nicaragua. -rc

I grew up in Pittsburgh and don’t remember hearing anything about the Freedom House Medics. I do remember the racism in my hometown during the 60s and 70s. I remember staying home to protest the integration plans of the schools, etc.

I know the Post Gazette (Pittsburgh’s newspaper) had articles about it over the past year or so, but since I no longer live in the city, I don’t always see interesting news.

Hopefully I will be able to see the documentary in the future. I think it is awesome that someone is trying to right a wrong.

Randy and Kit, thank you for sharing this. I still have my copy of Caroline from my early training. It was a very graphic and valuable resource.

First, I want to thank you Randy for writing this detailed article on Freedom House. I also want to touch on a few points. I started filming the documentary in 2001 and completed in 2010 (I retired from EMS in 2012 after a 41 year career). The documentary was supported with my 90% of my own funds. Medical companies were approached but I was turned down for support while making the documentary. In fact numerous EMS Educators and Anthologist Professors approach and endorsed my documentary to Laerdal. Excuses were made by Laerdal, then they never responded. Dr Safar was instrumental in Laerdal’s work into EMS.

I really wish I had more funds to put into post production, but I had exhausted my funds. Another reason for the quality of the showing, was that I had to play the film from a DVD player on a laptop and also the audio and video projector was set up in analog, so I was unable to show the doc in a digital format. Thanks again for a fine article and getting the word out about the Freedom House Ambulance Service.

Gene Starzenski / Producer Director

https://www.facebook.com/pages/Freedom-House-Street-Saviours/125924723916

—

It’s pretty sad that Laerdal, who had a significant business handed to them, couldn’t even acknowledge how they got started! -rc

Dr. Nancy Caroline (photo in the ambulance with the luggable defibrillator) looks an uncanny lot like Margaret Hamilton during her days as the lead Apollo flight software engineer.

Is the documentary still private? It sounds like something that desperately needs to go online.

—

Last I heard, nothing has changed about his position on that. -rc

Thank you for sharing the story of the Freedom House. I have been trying to research the history of women paramedics. This article mentions that there were two women paramedics in the Freedom House program.

I was certified as a paramedic in 1976, part of the first paramedic class of St. John’s Hospital in Springfield, IL. I worked for ALMH Hospital in Lincoln, IL. What else do you know about the history of women paramedics?

—

Very little: I’m not a historian. But it sounds like a worthy project that I’d like to see made into a book. -rc

BeaAnn! I’m an Emergency Medicine physician, subspecialized in EMS. I’m interested in creating a more firm timeline about the history of women in EMS. If you reply to this post, perhaps you could share some of your story about working as a woman in that field early in the time of female paramedics?

I was a nursing (LVN/LPN) student at Fitzsimons Army Medical Center in Denver (BS! It’s in Aurora!) in 1975 and 76. Having been in the Army for 7 years at the start of my training, I was educationally, in a military sense, ahead of most of my 82 classmates. So, being bored out of my gourd, I took what I believe was the 2nd EMT Class at Fitz. I’m not sure what text we used, but I know it was before Dr. Caroline’s text.

(This next is for “Kathy in San Diego” for reference.) Our class was comprised of both male and female Army Medics, and I think one or two Female Department or the Army Civilians (aka: “DACs”), which became funny during extrication from a burning building training. I am 6’5″ and weighed around 210 at the time. To show that even “little ladies” (the course instructor’s words, not mine) were capable of moving people my size, I laid on my back on the floor, and the smallest woman in class got me turned, got herself to her knees, and then on her feet, and carried me across the classroom. I believe she was about 5’2″ and maybe weighed 110. And, BTW, I did not “assist” her in any way, she did all of this on her own.

Much of what I have seen and read about the training given to the Medics of Freedom House, was copied and part of my training. At the time there were two categories of EMT’s, EMT & EMT-A, the “A” designation indicated that the person was trained and tested to fulfill the role inside an ambulance. We worked with the Emergency Room at Fitz, and with the Ambulance Service there. We also were allowed on runs with the Aurora FD in a trainee capacity.

One interesting note about the story of “Annie.” As it has been told to me since 1975, and as I have retold it when I have taught Basic Life Support (BLS) classes, Annie was supposedly modeled after Dr. Laerdal’s young teenaged daughter, who had died in a drowning accident in Austria. Your retelling of the story (Randy) is the first I have heard that version.

That’s about all I can remember from back that far, maybe if someone asks me a question or two, it will spark the memory.

BTW The training I received as an EMT did get put to use in my later career in the Army. I was the Assistant Non-Commissioned Officer In Charge (A-NCOIC) of the Emergency Room at Aberdeen Proving Ground, Maryland (which included HAZMAT situations and duties at Edgewood Arsenal) and I was the NCOIC of the Emergency Department of the 67th Evacuation Hospital (the actual community hospital) in Wurzburg, Germany at most times without an ER MD or RN. Did that for about 3 years in the 80’s.

—

The inspiration for Anne’s face is well documented, including on Laerdal’s web site, though I take issue with their claim that the doll is “extremely realistic in appearance.” That said, in 1955 Asmund Laerdal had saved his young son, Tore, who nearly drowned, which supposedly made him very agreeable when Dr. Safir suggested the collaboration. -rc

I have been waiting years to see this film. I don’t understand why one of the big EMS related equipment vendors has not used this an a sponsorship opportunity.

I was in New York City EMS’ second paramedic class in 1977, and we were given a Xerox copy/Loose Leaf bound pre-publication edition of Emergency Care in the Streets as our class text. I was surprised to learn years later that a number of other training centers were also permitted to use this landmark textbook. It was a great beginning.

—

I agree: sponsorship from an equipment vendor seems like a natural. Most, however, ironically don’t really strike me as “public service aware” these days. This would be a good way to change that perception. -rc

Being a mentor of Jack Webb, as a studio medic in covering Mark VII shows, Jack and I had discussed “Emergency” many times. He would tell me of his many lawsuits claiming ownership of the shows theme, but his producer of the series, Bob Cinader, had hired Dr. Ron Stewart of L.A. County General Hospital and Head of the Paramedic Program to review all the incoming scripts for the series, and had received permission from the L.A. County Board of Supervisors at the time to go forward with the series.

Naturally anything with Jack’s name on it was instant TV gold. Way ahead of his time, Jack had the originality of reality in dramatic form for television, i.e: “Dragnet”, “Adam-12”, etc before anyone else. It would take the Actor’s Strike of 1980 to create “reality TV” of today. Let us not forget Rescue 8, the mid-to-late 1950s TV series of L.A. City Firefighter First Responders starring Jim Davis as fireman Wes Cameron, and Lang Jeffries as fireman Skip Johnson, which may have been the grandfather TV version of “Emergency”.

I was certified as a Paramedic in early 1978 and helped staff the first midnight ALS unit to cover Times Square in NYC. We used Dr. Caroline’s text in our program, held at Beekman Downtown Hospital. I had no clue of the history of the earliest Paramedics and this story is fascinating. Thank you to those who made it possible and thank you for sharing it with those of us who followed in your footsteps.

Walter Brown Jr. was my first cousin and sadly Walt passed away from Cancer on August 29, 2019 at his home in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. He will sadly be missed with his “Larger than Life” personality and his sharp wit. Walter was a very loving and caring person and would give you the shirt off his back. The oldest of nine siblings, he was a “Gentle Giant” with a “Heart of Gold”, that loomed well over 6 feet tall. I will miss his big booming voice as he would often talk about his life and his many past experiences. I will also miss his wonderful smile that would light up the entire room. He was a very proud man and would always say his name, “Walter Brown Jr.”!

Within our family the apple didn’t fall too far from the tree. Both my daughter, Monica A.B. and I have followed in Walter’s footsteps by becoming EMT’s as well. My daughter Monica is an EMT-2 and is Nationally Certified while I only reached the rank as an EMT basic.

Walter Brown Jr., “Thank you for all your years of service and for being a Pioneer,” you will truly be missed. Rest In Peace cousin.

Monica A.P.

—

I’m sorry to hear, but grateful you took the time to post the news. P.S.: there’s no such thing as “only an EMT basic” — BLS skills save the most lives in EMS. -rc

Monica, I am so very sorry for your loss. Thanks for following in your cousin’s footsteps.

RIP Walter Brown Jr., and thank you for paving the road so many of us in EMS would follow later.

Thanks for sharing! I first got into EMS in 1972 and I’ve loved the profession ever since. I am certain none of us ever got into this profession with the expectation of making a lot of money; we did it because we wanted to help people in their hour of need. I used the original Nancy Caroline book in my paramedic class in 1981. She had a way of explaining things that made everything simple and yet so understandable. Thank God for these early EMS pioneers

RIP Walter Brown, Jr. Unknown to you, what you were being taught and innovating were lessons I learned a short time later. Thank you.

Thank you for this excellent and informative article. Dr. Caroline’s book was one of our required textbooks in Emergency Medical Care Assistant program here in Ontario, Canada. I had no idea of her impact and leadership until I read this article. Ontario, unfortunately, had several hiccups in its EMS genesis in the 1960s but thanks to Dr. Norman McNally, a former Canadian Army combat surgeon (WW2 I believe), he knew what medics were capable of doing and wanted civvie ambulance medics to do likewise. He was shut down due to budget and narrow-mindedness. The EMS training went through several iterations before EMCA became standard and before Paramedic became a designation.

RWG Walt. I will always remember our talks and the times we spent together. You are a great man who gave me great advice, encouragement and support. You talked to me and gave me insight on what it is to be a black man involved in prehospital medicine. The advice you’ve given me has helped me in my career as a paramedic and I thank you from the bottom of my heart for that.