In This Episode: To Boldly Go? No, this isn’t about Star Trek, but rather something even better: real life. This is the story of a 9-year-old with Uncommon Sense who was inspired to reach for the stars — and years later inspired a bunch of other kids growing up behind him.

035: To Boldly Go

How to Subscribe and List of All Episodes

Show Notes

- Help Support Uncommon Sense — yes, $5 helps!

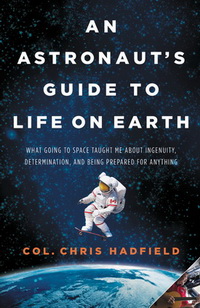

- Hadfield’s quotes are from his book An Astronaut’s Guide to Life on Earth — What Going to Space Taught Me About Ingenuity, Determination, and Being Prepared for Anything *.

- My blog post about Hadfield’s video and book is Ground Control to Major Tom.

Transcript

Welcome to Uncommon Sense. I’m Randy Cassingham.

What were you doing when you were 9 years old? I’d like to tell you about a guy who changed his life when he was 9. At the time, I was 10, and we saw the same thing happen. We were both inspired by what we saw, even if we took different paths. And by the way, his path was much more impossible than mine.

When Chris was 9, he and his family were at their island summer cottage. They didn’t have a TV set, so when there was something very special coming on, the neighbors invited them in. Chris remembers it with crystal clarity.

He said it wasn’t just his family and the neighbors: a lot of folks on this island getaway were there, jamming the living room to watch history being made on TV.

Chris said he and his brother, Dave, were together as they watched a grainy low-resolution black and white image of a man climbing down a ladder, and then stepping foot on the moon. It was July 20th, 1969.

Despite that low quality image, Chris said much more recently, “I knew exactly what we were seeing: the impossible, made possible.” When astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin went back into their lunar module after their “impossible” moon walk, Chris and his brother walked back to their own cottage.

“I looked up at the moon,” Chris said. “It was no longer a distant, unknowable orb but a place where people walked, talked, worked, and even slept. At that moment, I knew what I wanted to do with my life. I was going to follow in the footsteps so boldly imprinted just moments before. … I knew, with absolute clarity, that I wanted to be an astronaut.”

Yeah, well, so did you, probably, if you remember that day. What kid didn’t? But Chris had a barrier to his dream: he was Canadian, and Canada didn’t have a space program. They didn’t have astronauts, and there was no path for a Canadian to become an astronaut. So, Chris said, he “knew, as did every kid in Canada, that it was impossible. Astronauts were American. NASA only accepted applications from U.S. citizens.”

On the other hand what did “impossible” mean anymore: he had just witnessed the impossible live on TV. “Neil Armstrong hadn’t let that stop him,” he reasoned. “Maybe someday it would be possible for me to go,” he said, “and if that day ever came, I wanted to be ready.”

And that’s what set Chris apart from most of the other kids who watched the moon walk that night. There was no path for him to become an astronaut, so, he said, “I had to imagine what an astronaut might do if he were 9 years old, then do the exact same thing. I could get started immediately. … My dream provided direction in my life. … What I did each day would determine the kind of person I’d become.”

He worked extra hard in school, and earned spots in advanced classes. Hell, he says he even learned how to think in school! — “critically and analytically,” he said, “to question rather than simply try to get the right answers.”

He may not have any path to become an astronaut, but at 9 years old, he was on a mission.

It helped that his father was an airline pilot: that meant he already had an interest in airplanes, and he knew that the astronauts of that time were mostly fighter and test pilots. By the time he was 13, his dream took a step forward: he joined the Royal Canadian Air Cadets, which Chris says was sort of a cross between the Boy Scouts and the Canadian Air Force. They even taught him how to fly: Chris got his glider plane license at age 15, and the next year graduated to powered planes.

He was also realistic: even if he couldn’t be an astronaut, “I never felt that I’d be a failure,” he said, because knowing it was impossible for him, “it would be pretty silly to hang my sense of self-worth on it.” Still, he applied to Canada’s Royal Military College, joined the Royal Canadian Air Force, and learned to fly fighter jets.

In 1983, the Canadian government did something that, he said, made his dream “marginally more possible”: it recruited and selected its first six astronauts. Chris wasn’t one of those selected, but Marc Garneau was, and he was the first Canadian to fly in space in 1984. So, Chris said, “I was even more motivated to focus on my career.”

Later, Chris joined an international exchange program: he got to spend some time working with the U.S. Navy, and got to go to the U.S. Air Force Test Pilot School at Edwards Air Force Base. You know: the place where Neil Armstrong worked before he became an astronaut?! While in the U.S., he also got a master’s degree in aviation systems, in May 1992.

And that put him in a pretty good spot when NASA announced the selection of four more Canadians as astronauts — from a field of 5,330 applicants. This time, Chris Hadfield was one of the four. He helped design a new digital instrument panel for the Space Shuttle — what pilots call a glass cockpit. He served as the CAPCOM for shuttle missions: the guy allowed to actually talk to the astronauts up in space — only other astronauts get to do that. He was CAPCOM for 25 shuttle missions, and rose to be the Chief CAPCOM.

And yes, as you probably know, he got to fly in space, starting with the Space Shuttle Atlantis in November 1995. It took him 27 years to achieve his dream as a 9-year-old.

There surely was some luck involved, but the primary factor in achieving his dream was not just saying at 9 that he wanted to be an astronaut, but by making and following a step by step plan to be one. He used Uncommon Sense “to imagine what an astronaut might do if he were 9 years old, then do the exact same thing.” And it worked.

In all, over three missions he spent 166 days in orbit, and had nearly 15 hours of EVA time — spacewalking — and in fact was the first Canadian to walk in space, and the only Canadian to ever board Russia’s Mir space station.

Clearly he’s a brainy and determined guy, but he was also cool. On his last space mission, Hadfield launched to the space station in December 2012, and joined the Expedition 34 mission that had been going on for a couple of months. When the Expedition 34 members went back to Earth, Hadfield stayed — as Commander of the International Space Station’s Expedition 35, until he left space for the last time on May 13, 2013.

During those 144 straight days in orbit on the station, the wonder of his 9-year-old childhood re-appeared: Hadfield spent a lot of time using social media to spread photos, videos, and his thoughts about his experiences in space, and gained a major following. I have little doubt that following included kids in many countries, some of whom were surely inspired to set their sights a little higher.

Plus, he did something else that was awfully cool: there was a guitar a previous astronaut had brought up to the station and left there, and Hadfield, a long-time guitarist, enjoyed playing it. At the urging of his son Evan, Commander Hadfield accomplished one last first as an astronaut: he recorded a music video in space: a special version of David Bowie’s “Space Oddity” where the astronaut lives — Evan had altered the lyrics with the blessing of David Bowie. It was posted on Chris’s last day in orbit, and when he landed back on Earth the next day, a Russian crew handler told him he liked his video! It had gone viral. The official Youtube post of the video now has more than 43 million views.

Once Hadfield was home, and retired from the astronaut program (and the RCAF), he wrote a memoir: An Astronaut’s Guide to Life on Earth — What Space Taught Me About Ingenuity, Determination, and Being Prepared for Anything, which I wrote about in my blog in 2013. There, I wrote that Hadfield’s book is “frankly brilliant — and (hint!) a great book to give to young folks to read, like your kids or grandkids, especially if they have any interest in space or science. Highly recommended for you, too, of course, and you don’t have to be a space nerd like me to get a lot out of it.” I’ve said in other episodes that it’s truly smart to expose kids to ideas like this when they’re young, and 9 is certainly not too early! It’s how they develop Uncommon Sense, because most kids aren’t as lucky as Hadfield was: his school taught him to think — “critically and analytically.”

Once Hadfield was home, and retired from the astronaut program (and the RCAF), he wrote a memoir: An Astronaut’s Guide to Life on Earth — What Space Taught Me About Ingenuity, Determination, and Being Prepared for Anything, which I wrote about in my blog in 2013. There, I wrote that Hadfield’s book is “frankly brilliant — and (hint!) a great book to give to young folks to read, like your kids or grandkids, especially if they have any interest in space or science. Highly recommended for you, too, of course, and you don’t have to be a space nerd like me to get a lot out of it.” I’ve said in other episodes that it’s truly smart to expose kids to ideas like this when they’re young, and 9 is certainly not too early! It’s how they develop Uncommon Sense, because most kids aren’t as lucky as Hadfield was: his school taught him to think — “critically and analytically.”

The odds are very low that you are 9 years old right now, but even if you’re 49, or even 89, you can still set your mind to accomplish something. Maybe even the “impossible.” That’s one way to practice Uncommon Sense, and it’s never to late.

The Show Page for this episode, which includes Hadfield’s photo, music video, and a place to comment, is thisistrue.com/podcast35.

I’m Randy Cassingham … and I’ll talk at you later.

– – –

Bad link? Broken image? Other problem on this page? Let Me Know, and thanks.

This page is an example of Randy Cassingham’s style of “Thought-Provoking Entertainment”. His This is True is an email newsletter that uses “weird news” as a vehicle to explore the human condition in an entertaining way. If that sounds good, click here to open a subscribe form.

To really support This is True, you’re invited to sign up for a subscription to the much-expanded Premium edition.

In response to your comment about age: Once I read a letter from a man to Dear Abby, or maybe her sister (Ann Landers), in which he said that he had always wanted to go to medical school but was unable to earlier in life because of various circumstances. He said that he finally had a chance to go to medical school, but since he was now thirty he wondered if it would be a wise decision. “After all”, he wrote, “with the time the school will take, then internship, and residency, and then setting up practice, by the time I am established it will take ten years and I will be forty!”

I just loved her non-responsive response. She wrote, “How old will you be in ten years if you don’t go to medical school?”

I sort of forgot about his letter and her response until some years later when I again was reading her column and the person writing in wrote that he was the one who had years earlier written the first letter and he had taken her “advice” and gone to medical school and he was now established in the medical profession and loving every minute of it, and just wanted her to know how grateful he was to her.

I sort of kept the entire thing in mind a little better after that. But, what really cemented it into my memory was some years later reading another person’s letter to her in which he summarized the previous story and then added that he was so struck by those two letters that he too went to medical school later in life and he too was loving being a doctor and so grateful for her wisdom and advice.

How old will you be in the years ahead if you let age dictate your decisions?