In This Episode: How does a man use his years of experience working for IBM as they introduced computers to business, leverage that experience to invent a worldwide phenomenon that you have used many, many times? He uses Uncommon Sense.

047: Standing in Line

Tweet

How to Subscribe and List of All Episodes

Show Notes

- Help Support Uncommon Sense — yes, $5 helps!

- The full 1995 interview with Don Wetzel, which I used as my primary source, is here.

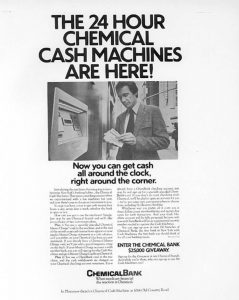

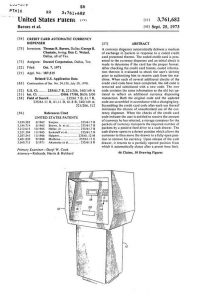

- There are several photos in the transcript.

Transcript

I’m Randy Cassingham, welcome to Uncommon Sense.

This episode is brought to you by listeners who support Uncommon Sense so that there are no commercials to interrupt your listening. See thisistrue.com/patrons for details, to join them, and choose from extra supporter benefits.

Donald Wetzel worked for IBM, using the company’s famous punchcards to serve businesses before IBM even made computers. They did tasks like running payroll and accounts receivable. He thought IBM was a great company, and it paid well, so he expected to work there until he retired. He remembers the biggest problem he had at the time was working with banks: as IBM started making computers, those computers really wanted to work with numbers, and amazingly, in the 1950s, banks didn’t use account numbers! Bank accounting was done by hand, often with the help of mechanical calculators (which IBM also made), and customer accounts were filed by the customers’ names.

“So we first had to sell them on the idea of putting an account number to a customer name,” Wetzel remembered in a 1995 interview with the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, “and then we’d address getting them to buy the equipment.” He remembers bankers resisted, telling him, “our customer is not a number to us, it’s a name.”

Wetzel became a “special representative” to banks — they became his specialty at IBM. “It required a lot of travel,” he said, “but it was stimulating because these were dynamic times in the banking industry. Computers now had really come out. The bankers realized, ‘well yes, we have to move forward and we are going to number our accounts and it looks like these computers will help us.’ So it was exciting; those were exciting years.”

After a few years they wanted to promote Wetzel again, to IBM’s New York headquarters. He didn’t want to go: “It was going to be a staff job.” In Texas, he said, “I was right on the firing line, which I enjoyed a lot more.” Unfortunately his bosses insisted. Wetzel had an offer from a friend to come be the Vice President of Product Planning for a Dallas company called Docutel. It was 1968, and the company’s main business line at the time was …automated baggage-handling equipment. He took the job.

Not surprisingly that job had some travel too, and as he was heading out for a business trip on a Friday afternoon, Wetzel realized he needed some cash. It was close to 5:00 p.m. by the time he got to the bank, and there was a long line of people wanting cash for the weekend. And here’s where his Uncommon Sense kicked in big time, driven by a combination of years with IBM working in the computer industry as it started up, and working with banks.

The idea hit him like a giant wad of cash. “So much of what they were doing was withdrawals,” he said, “and it struck me as I was standing in line, that there ought to be a machine that could do that.” And as he watched the clock tick toward closing time, he extended the thought further. He realized that such a machine was “something that didn’t need the bank to be open — customers could get money [anytime], seven days a week. I thought it would be marketable.”

The idea, if you haven’t guessed it already, was that while standing in line, Wetzel invented what became known as the ATM, or Automated Teller Machine. And you know it was marketable!

“The idea came into my mind very quickly,” he said. “I went back to our people at Docutel and told them what was going on, and I thought that we could build a machine that would perform at least 90 percent, perhaps more than 90 percent, of all the transactions processed by a teller.”

It took the company 11 months to develop the machine at a cost of $4 million — which the small company had to borrow from banks! There were three things they had to invent to make the machine work: “We had to develop a card reader that would read this card,” Wetzel said. “We had to develop a dispensing unit that would dispense the dollar bills. And we had to develop a printer that would print the transaction, give a copy to the customer, and a copy retained in the machine to be processed in the back office as they did a check — that’s how the account was debited.”

Remember, this was only 10 to 15 years after banks started assigning numbers to their customer’s accounts so they could use computers! And in the late 1960s, computers weren’t all that powerful — or connected.

“In those years there was very little online to the host computer; almost none,” Wetzel said, “because those computers were used in a back-office environment. There were no such things as teller terminals … as we know them today. So it was going to be an off-line machine … because we could not get them online.”

There were other challenges, too: bank presidents didn’t necessarily understand what the $35,000 machine could do for their business. And that cost didn’t include installation. After giving one bank executive a sales pitch, one Docutel salesman remembered the executive replied, “Let me get this straight. You want me to poke a hole in the wall of my branch. Then you want me to stick a one-ton machine through that wall. Then that machine is going to spit money out onto the sidewalk. Do I have it right so far?”

Bankers thought that their customers wanted the personal touch — to interact with tellers. After all, hardly anyone at that time had used a computer or a computer terminal, including most bankers. Wetzel’s team asked the University of Dallas to do a study. “It turned out that younger people were more likely to use it and the older people probably would not,” Wetzel remembers. “Banks were converting from commercial banks to retail banks, so they wanted to offer something to younger people, especially the younger people because they were reaching that age beyond college, starting their first job, and banks wanted them as customers. They felt like ‘we have to offer some services that we haven’t been offering.’ So this went hand in glove with the ATM — it helped the bank serve its customers; it would attract those younger customers that they wanted.”

And as banks saw their competitors snap the machines up to do business, reducing their need to pay as many tellers salaries and benefits, the ATM caught on pretty fast. So did the competition, but Docutel had a major head start. By mid-1975, 500 banks had 3,000 ATMs in operation — and more than 80 percent of them were made by Docutel. There are now 3.5 million ATMs in operation around the world.

“Frankly, I am surprised that [the ATM has] the same functions as it did back then,” Wetzel said this year as he turned 90 years old. “Sure, it is faster and looks better now. But it gives me a great deal of pleasure because I think we really did our homework.”

So much so that one of the innovations the company’s engineers came up with was key to the ATM’s success: if the ATMs weren’t online, how did it know the account number to debit from, and whether the PIN the customers entered to access their cash was correct? It was all encoded in the ATM card the customers used, on an encrypted magnetic strip. Banks then thought such a machine-readable strip would be very helpful with another innovation to their business enabled by adding I.D. numbers to accounts: bank credit cards, which the Bank of America had introduced in 1958. Credit cards didn’t have magnetic strips when the ATM debuted, but they were quickly adopted. And then Docutel innovated on that innovation: they created the first “pay at the pump” credit card readers, built right into gasoline pumps. And yes, the oil companies resisted that innovation too.

Docutel died off in the 1980s, in part because they were slow to make their machines work online — connected to the banks’ mainframes to ensure the customers’ accounts had enough to cover their withdrawals. There was one big competitor making ATMs that had a real edge for that idea: IBM.

Wetzel was gone well before then anyway: he quit Docutel in 1973 to start a couple of other companies to serve the banking industry. And here comes his Uncommon Sense again: “I believe we were the first company that put ATMs in supermarkets,” he said. “We had devised a formula that we would buy the machines from the manufacturers, we would place them in supermarkets, and we would charge so much a transaction and the supermarkets would get so much. That went very well, in fact so well that in 1984 we were bought by Docutel.” He retired for good in 1989.

Wetzel still lives in Texas, and had one big confession to make regarding his wife, Eleanor, who is 88 years old. “I am embarrassed to say, she has never used an ATM,” he admits. “At the time, Eleanor was busy being a mother and she was scared she would put her card in the machine and she would never get it back. She never had the desire to use one, and she never changed her mind.”

To comment on this episode, or read the transcript because I mumbled something, the Show Page for this episode is thisistrue.com/podcast47

I’m Randy Cassingham … and I’ll talk at you later.

– – –

Bad link? Broken image? Other problem on this page? Use the Help button lower right, and thanks.

This page is an example of my style of “Thought-Provoking Entertainment”. This is True is an email newsletter that uses “weird news” as a vehicle to explore the human condition in an entertaining way. If that sounds good, click here to open a subscribe form.

To really support This is True, you’re invited to sign up for a subscription to the much-expanded “Premium” edition:

Q: Why would I want to pay more than the minimum rate?

A: To support the publication to help it thrive and stay online: this kind of support means less future need for price increases (and smaller increases when they do happen), which enables more people to upgrade. This option was requested by existing Premium subscribers.

Donald Wetzel shouldn’t get credit for inventing the ATM. He invented the first AMERICAN ATM, but others had been used in England and Japan.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Automated_teller_machine

—

Yes, there were attempts to make a cash dispenser for decades before, but Wetzel is already credited for inventing the first practical, non-bank-specific, ubiquitous ATM. -rc