In This Episode: One person with Uncommon Sense can have a profound effect on the world. Wait until you hear the story of Doug Engelbart: he’s the visionary behind many of the technologies you use most every day.

050: The Mother of All Demos

How to Subscribe and List of All Episodes

Show Notes

- Help Support Uncommon Sense — yes, $5 helps!

- Several photos are interspersed with the transcript below.

- “The Mother of All Demos” video is also below.

- The Doug Engelbart Institute still exists, and has more to explore at its site.

- The full text of Vannevar Bush’s essay “As We May Think” is still available at The Atlantic.

Transcript

I’m Randy Cassingham, welcome to Uncommon Sense.

During World War II, Douglas C. Engelbart was in college at Oregon State, but was drafted and served as a radar operator in the Philippines. Engelbart was a curious type, and radar was a pretty new thing at the time, so he was quite interested to read an article in the magazine The Atlantic written by Vannevar Bush, the head of the U.S. Office of Scientific Research and Development, the government agency that was in charge of developing radar and, later, Bush got the Manhattan Project going. That was just Bush’s wartime assignment: before and after that, he was the head of a different government agency: the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics, or “NACA” — the predecessor of NASA, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Bush was not just smart, he was well tied in to the latest in thinking about technology.

His article was titled “As We May Think”, and it’s still considered a visionary, milestone essay for its time. Bush used the space to express concern regarding the direction of scientific progress: it was more about destruction, rather than knowledge and understanding. Perhaps that’s not surprising considering the world war, but he was looking toward the future, toward the long-term. Bush went on to suggest that what the world needed was what he called a “memex” — short for memory index — which de described as a sort of collective memory machine that would make knowledge more accessible. Through this machine, Bush hoped to transform the expansion of information into an expansion of knowledge.

Engelbart was transfixed. After the war, he went back to Oregon State and finished his degree. Once he had that in hand, he went to work at NACA. But in 1950 and newly married, Engelbart started thinking about his goals and thoughts about the bigger picture — the long term — just as Bush had done in 1945.

- He wanted to make the world a better place.

- He realized to do this, it required organized effort.

- Harnessing human intellect was the key to bring effective solutions.

- Large improvements in how intellect is harnessed is important, and

- Computers can be the vehicle for that improvement.

Sounds a lot like the memex, doesn’t it? But Engelbart called it the Dynamic Knowledge Repository, recognizing that not only would it grow as it was fed knowledge, but it would grow exponentially. He said the DKR will enable humanity to develop a collective I.Q. greater than any individual’s I.Q. That’s a tall order, but you can probably see where this is going.

Engelbart went back to school, getting his Masters and Ph.D. in Electrical Engineering, and in 1957 he went to work at the Stanford Research Institute in Menlo Park, California, created by Stanford University to advance scientific knowledge and to benefit the public at large, not just the university’s students. You can see why he was attracted to the place.

By 1962, Engelbart published his own vision of the future — but even more importantly, he laid out how to achieve it. The title of his paper: “Augmenting Human Intellect: A Conceptual Framework.” It was impressive, and caught the attention of DARPA, the Defense Department’s Advanced Research Projects Agency, which funded Engelbart to continue his work.

With that vote of confidence, Engelbart founded what SRI called the Augmentation Research Center — and he called the Augmented Human Intellect Research Center. To reach his vision, Engelbart needed a “working station” where people could see information — and that working station, which was later shortened to “workstation,” was the way to access what he called the “oNLie System”, or “NLS”. Engelbart, with his experience with radar displays, thought a graphical interface would be more useful than the typewriter-like computer terminal/printers that were common at the time, to interact with that network of interlinked computers.

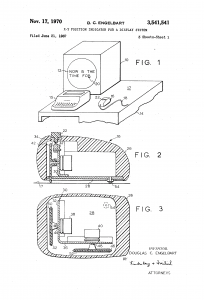

Then, to work with the information on the graphical display, in 1963 he came up with a concept to do it. One of his team members, Bill English, helped him build it. English, seeing this small device with a cable coming out the back, called Engelbart’s device… a mouse. “SRI patented the mouse, but they really had no idea of its value,” Engelbart said later. “Some years later it was learned that they had licensed it to Apple Computer for something like $40,000.”

But let’s not get ahead of ourselves!

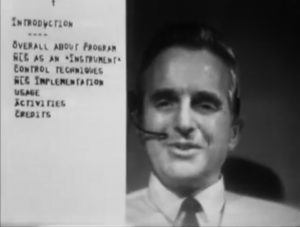

Five years later, in 1968, and still 15 years before the introduction of the Apple Macintosh, all of Engelbart’s visions came together at the Association for Computing Machinery’s Fall Joint Computer Conference in San Francisco, California. At his presentation, Engelbart, tied in to his lab in Menlo Park, demonstrated to more than 1,000 computer scientists what was coming out of his lab at the Augmentation Research Center: not just the video display and mouse, but also a chord keyboard, video conferencing, teleconferencing, hypertext, word processing, hypermedia, dynamic file linking, revision control, collaborative editing, and even copy and paste using the mouse! The whole idea was for each researcher to have such a computer system, but they needed to be tied together to allow information to be shared rapidly among the collaborating scientists.

Remember, this was 1968! It took another year before a computer at SRI became the first connected node of the ARPAnet, DARPA’s computer network that evolved into the Internet. The first link was made to SRI from the University of California in Los Angeles. Engelbart then created the Network Information Center, which became officially responsible for registering Internet domain names. I’ll bet he was glad to let that little project go to somebody else!

In 1994, journalist Steven Levy, in his book “Insanely Great: The Life and Times of Macintosh, the Computer That Changed Everything,” described Engelbart as giving the presentation with “a calming voice from Mission Control as the truly final frontier whizzed before their eyes.” And then, he said, “It was the mother of all demos.”

The name stuck. And the best part is, Engelbart’s entire hour and 45-minute presentation, minus a couple of gaps, was recorded on film: you can watch a digitized version on this episode’s Show Page. The gaps, by the way, were when the camera operator had to load in a fresh roll of film!

The presentation was a sensation, and Engelbart’s staff quickly grew. Some of them stayed on, while others absorbed the revolution going on at the Augmented Research Center and moved to other research positions, such as at Xerox’s Palo Alto Research Center, one city to the south.

Apple co-founder Steve Wozniak says Engelbart’s paper, made real by the Mother of All Demos, created a framework which provided “for everything we have in the way computers work today. What he did was absolutely brilliant and so far ahead of its time back then. He saw where the future was going to go.”

“The conference attendees were awe-struck,” says technology journalist John Markoff. “In one presentation, Dr. Engelbart demonstrated the power and the potential of the computer in the information age. The technology would eventually be refined at Xerox’s Palo Alto Research Center and at the Stanford Artificial Intelligence Laboratory. Apple and Microsoft would transform it for commercial use in the 1980s and change the course of modern life.”

In 1970, as the host of the newly connected first remote node of the ARPAnet, Engelbart released another paper: “Intellectual Implications of Multi-Access Computer Networks.” In that paper he described the emergence of a new “marketplace” representing “fantastic wealth in commodities of knowledge, service, information, processing, and storage,” with “a vitality and dynamism as much greater than today’s, as today’s is greater than the village market.”

In other words, Engelbart’s visions didn’t just predict the computer and Internet industries we have today, he sparked them as a way to share information and “augment” collective human intelligence.

Yet he never profited from his extraordinary vision. “He was in the shadow of the people who would get credit for his ideas and make billions of dollars from them,” Levy says. Howard Rheingold, author of “Tools for Thought: The History and Future of Mind-Expanding Technology,” agrees: Engelbart, he says “wanted to help people solve problems, and he saw the world as having very significant problems. That is not something you can get a patent on, start a company or make a fortune on. Bill Gates’ vision was a computer on every desk running Microsoft software. Doug had a much larger humanitarian vision.”

The real problem was, as Steve Wozniak said, Engelbart was ahead of his time; it would take years to implement his visions — 15 years to get to the first Macintosh, now considered a crude forerunner of the computers of today. So his funding ran out, his home fell into disrepair, his OLS computer concept was sold in 1977, and he was mostly forgotten… for awhile.

In 1997 Engelbart was awarded the Lemelson-MIT Prize, and the Association for Computing Machinery’s Turing Award. In 1998, the ACM’s Computer-Human Interactions group awarded him their Lifetime Achievement Award. In 1999 the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers awarded him the John Von Neumann Medal. And in 2000, he received the National Medal of Technology and Innovation from the President of the United States.

That last award’s citation says the Medal was given to Engelbart “For creating the foundations of personal computing including continuous, real-time interaction based on cathode-ray tube displays and the mouse, hypertext linking, text editing, on-line journals, shared-screen teleconferencing, and remote collaborative work. More than any other person, he created the personal computing component of the computer revolution.”

Engelbart is also remembered in Engelbart’s Law: the observation that the intrinsic rate of the growth in human performance is exponential. It recognizes that his work in augmenting human performance was explicitly based on the realization that although we make use of technology, the ability to improve on improvements (or “getting better at getting better”) is an entirely human invention.

And the progression of his entire life demonstrates that he had an uncommon measure of Uncommon Sense.

Dr. Engelbart retired in 2008 and, five years later at 88 years old, he died in his sleep from kidney failure at his home in Atherton, California — one city north of Menlo Park. Still, he saw modern computers. He saw the Internet grow from the computer at SRI to what it is today. He saw the smartphone! And, finally, he saw recognition for his work.

Late in his life, asked about what’s coming in the future, he said, “Boy, are there going to be some surprises over there.”

The Show Page for this episode, where you can comment, see a couple of photos of Doug Engelbart, see the cover page of his 1967 patent for the mouse, and watch his Mother of All Demos — it’s at all thisistrue.com/podcast50.

I’m Randy Cassingham … and I’ll talk at you later.

– – –

Bad link? Broken image? Other problem on this page? Use the Help button lower right, and thanks.

This page is an example of my style of “Thought-Provoking Entertainment”. This is True is an email newsletter that uses “weird news” as a vehicle to explore the human condition in an entertaining way. If that sounds good, click here to open a subscribe form.

To really support This is True, you’re invited to sign up for a subscription to the much-expanded “Premium” edition:

Q: Why would I want to pay more than the minimum rate?

A: To support the publication to help it thrive and stay online: this kind of support means less future need for price increases (and smaller increases when they do happen), which enables more people to upgrade. This option was requested by existing Premium subscribers.

I so remember this in 1972…we had a similar keyboard, mouse setup to start learning on… I wish I still had the apple 1 and 2 that the instructor gave me before I took over the class in 1980. I donated it to a local museum.

—

At least that’s better than trashing it! -rc