In This Episode: Sometimes people are forced into thinking up solutions because of an emergency. But when they practice Uncommon Sense, they can leverage their thinking into, once in awhile, saving millions of lives. This is the story of a married couple who did just that.

053: Leveraging Uncommon Sense

Tweet

How to Subscribe and List of All Episodes

Show Notes

- Help Support Uncommon Sense — yes, $5 helps!

- The episode about the EpiPen is a must-hear: 032: “Give Me a Shot at It. I’m an Engineer”.

- The website for the Medic Alert Foundation.

- The AT&T advertisement is from here.

- See the transcript for the photos mentioned.

Transcript

I’m Randy Cassingham, welcome to Uncommon Sense.

In 1953, while her parents were out of town, 14-year-old Linda Collins of Turlock, California, cut her finger badly enough that a neighbor rusher her to the hospital. Her uncle was a doctor, and he treated her that day. It sounds like it was a dirty cut, and protocol calls for a tetanus shot. Before giving that to her, the doctor checked his niece for sensitivity to the serum, using a scratch test: scratch off a little skin and apply a tiny bit of the serum to see if there is a bad reaction. It’s a good thing he did, since just the test put Linda into anaphylactic shock — it turned out she was highly allergic to the tetanus antitoxin. “It was five days before we knew whether she would live or die,” said her mother, Chrissie. She survived, but it got her parents, Chrissie and her husband Marion, who was a surgeon, thinking.

Doctors see anaphylactic shock all the time. It’s much more than a simple allergic reaction: the victim’s blood pressure can crash, their airway can swell closed, and if that happens, they’ll quickly die without treatment — and sometimes, even with treatment. Common allergens that cause anaphylaxis include bee stings, peanuts and other foods, various drugs, and more. And, in those days, they were seeing it from penicillin, too, which prompted a lot more scratch tests.

Anaphylaxis has to be treated immediately to reduce the chance of permanent damage or death, and the emergency treatment for it is an injection of epinephrine. There’s a self-administered version you’ve heard of, the EpiPen, which was discussed in Episode 32, which I’ll link to on the Show Page.

Linda’s parents realized that their daughter was one of many who had a life-threatening allergy. If just the test put Linda into anaphylactic shock, they knew that an actual tetanus shot would kill her. They wanted to be sure no doctor or nurse (these were the days before street medics) ever gave her that shot. How could they warn the medical profession of her vulnerability? When Linda was going out, the Collins’s would stick a paper note into her bracelet, or pin it to her sweater, that advised doctors of her allergies, just in case.

When Linda was ready to go off to college a few years later, Dr. Collins knew a piece of paper wasn’t the permanent solution Linda needed. “My dad thought of a dog tag or tattoo to protect me, but I convinced him to make a bracelet,” she once said. “Dad designed it with the words ‘Medic Alert’ on the front in red.” On the back, the several things that could give her an anaphylactic reaction were engraved into the metal. To get doctors’ attention, Dr. Collins put the Staff of Asclepius, the Greek god of healing, on the front too: it’s a common symbol of the medical profession. Chrissie Collins said it caught on quickly. “Other people saw it and said, ‘I ought to have one of those. I am allergic,’ or ‘I have a daughter with diabetes’,” she said in 1978. “We began having [the bracelets] made up, one at a time.”

And then that’s when the Uncommon Sense shoe really dropped. First, that there are an awful lot of people who need their medical conditions communicated to the people who are trying to save them when they can’t communicate for themselves. But a bracelet isn’t really enough: doctors generally need a lot more information than what can be engraved legibly on a little bracelet medallion, so the idea kept expanding: how about a toll-free phone number on it, and an I.D. number, and doctors could call, give the I.D. number, and get all the details they needed for patients who can’t talk for themselves?

In 1956, the Collins’s established a non-profit organization to put the growing idea into action. It’s called the MedicAlert Foundation, and it’s still operating today. The bracelet is still the most popular tool, and there are also necklaces, and even watches — and emergency rooms and first responders look for them when they have patients having an emergency who cannot communicate.

But to get their idea off the ground, the Collins’s needed a bunch of pieces of the puzzle in place. They needed a file system that someone could get to easily and retrieve and communicate the needed medical information quickly. And remember, this was well before small office computers. Of course, they needed that someone: a staff with at least some medical training and ability who would be available by phone 24 hours a day, seven days a week, including holidays. Medical students and even doctors volunteered to take shifts on the phones. And then they needed to get the word out to people with medical conditions that made it more likely they couldn’t speak for themselves. And to do all that, they needed a fair amount of money.

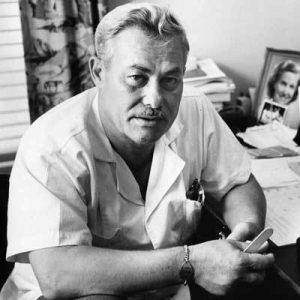

In the beginning, most of that money came from the Collins family: Dr. Collins put in $30,000 in the first two years because he knew he could save lives if he had information like that early on when treating his own patients in an emergency. In fact, he once said, “I think I can save more lives with MedicAlert than I’ll ever save with my scalpel.”

In 1960, a national magazine ran an article on the foundation, and told readers how to get a bracelet. Within the week, orders for more than 100,000 bracelets arrived in the mail. “We were not prepared,” Chrissie said. The family — the couple had four children — were running the foundation out of their house, and mail piled up on the floor. There’s a photo of that on the Show Page. Chrissie said they enlisted “the whole town of Turlock” to get the bracelets out the door as quickly as possible.

The idea continued to catch on. In the 1960s, the American Medical Association signed on to help. The concept started to spread internationally: they still operate in multiple countries.

In the 1970s the foundation could computerize its records — though Dr. Collins died in 1977, leaving the rest of his family to keep things running. The American Hospital Association endorsed MedicAlert, helping to spread the word.

In the 1980s, insurance companies and other foundations signed on as partners, including the Epilepsy Foundation and the American Diabetes Association. Celebrities pitched in to make public service announcements. Comedienne Carol Burnet was the symbolic one-millionth member, and proudly posed for a photo with her bracelet: I have that on the Show Page too.

In the 1990s, Chrissie Collins was given the Citation of Distinguished Service by the American Medical Association, the highest honor the AMA gives to a non-physician, recognizing her and her family’s pioneering work in public health. The foundation went online with a web site, and today members can log in and update their medical information anytime something changes.

In the 2000s, Chrissie died in 2001 at 94 years old, but she had set things up to continue without her, with a professional staff. And, sadly, Linda herself died in 2004, not of an allergic reaction, but from the breast cancer she had fought for 20 years.

Today, the MedicAlert Foundation has more than 100 full-time employees to keep up with it all, and they estimate they’ve helped save more than four million lives. Dr. Collins was absolutely right: doctors can save more patients when they know what’s going on with them. The idea helps not just people with allergic reactions, but diabetes, epilepsy, heart problems, Alzheimer’s and other dementias, and one that’s more important lately: that you’re taking blood thinners.

As a street medic going back to the mid-1970s myself, I’ve been aware of MedicAlert for decades. And in my view, there are actually two significant problems with the system: one, not enough people sign up with them when their medical condition really calls for it. Every time that I’ve looked for a bracelet or necklace with a patient who couldn’t communicate in a medical emergency, I haven’t found one, and they could have made a difference. And two, a lot of for-profit companies thought they could make a lot of money providing such a service in competition with the non-profit, and fractured — and confused — the market. There was no longer just one place to go for the emergency medical information.

Especially in recent years, though, some of that is good: one thing that pretty much everyone carries around with them these days is a smartphone, and both the iPhone and Android platforms now have built-in ways for medical professionals to get similar information from a patient’s phone even if it’s locked …but only if people set it up in advance and remember to keep the information up to date!

A lot of those for-profit companies have shut down over the years as they realized how expensive it is to run such a system, leaving those customers in the lurch. So it’s nice that MedicAlert still exists, and they can remind patients to periodically update their information, and give them tools to do it anytime their conditions change.

But let’s make something clear, because this isn’t a public service announcement for this non-profit foundation. Rather, it’s a celebration of the Uncommon Sense that the Collins family showed by not just helping Linda avoid medical treatments that could kill her, but by leveraging their ideas to help millions and millions of others.

For photos, links, and a place to comment, the Show Page for this episode is thisistrue.com/podcast53. And remember to help keep the podcast going: listeners help with contributions so that there are not commercials interrupting the episodes, and we need you to help too. Thanks much.

I’m Randy Cassingham …and I’ll talk at you later.

– – –

Bad link? Broken image? Other problem on this page? Use the Help button lower right, and thanks.

This page is an example of my style of “Thought-Provoking Entertainment”. This is True is an email newsletter that uses “weird news” as a vehicle to explore the human condition in an entertaining way. If that sounds good, click here to open a subscribe form.

To really support This is True, you’re invited to sign up for a subscription to the much-expanded “Premium” edition:

Q: Why would I want to pay more than the minimum rate?

A: To support the publication to help it thrive and stay online: this kind of support means less future need for price increases (and smaller increases when they do happen), which enables more people to upgrade. This option was requested by existing Premium subscribers.

“…both the iPhone and Android platforms now have built-in ways for medical professionals to get similar information from a patient’s phone even if it’s locked …but only if people set it up in advance.”

But how? I’m in Canada, and when I look at MedicAlert’s web page, it has a link to “my medicalert” which can help me with meds (of which I have none) and other things I can do — but nothing about my question.

My Samsung A20 has Android version 9.

—

What’s built into iPhones and Android phones is another way to set something up in your phone, and is not related to MedicAlert. A quick Google search for “samsung a20 emergency medical information” brought up several pages at samsung.com, which is where I would start to look. -rc

In Android 10 on a Pixel phone you can access and set up emergency information through Settings -> About Phone -> Emergency Information. It’s probably in a similar place on yours (though Samsung is known for moving things around, so it’s not guaranteed).

I’m debating whether to go bracelet or necklace for Medic Alert. From an EMS perspective, is one better? Also, my husband can’t wear his bracelet, and won’t wear a necklace. Is a key fob worth it, or even checked?

—

Between the bracelet and the necklace, what you’ll wear is “best.” Other than that, I’d say there’s a preference for a bracelet, since that’s where we would look first. A key fob almost certainly won’t be checked. Go for something on his phone. (You should have that too — two sources of info are better than one!) -rc

A tattoo can be useful in some cases. My friend is a Type 1 Diabetic. He has “Type 1 Diabetic” tattooed on his wrist — where EMS would look for a MA bracelet. He does not have any other tattoos to obscure the area. A “sleeve” of tattoo work would make such a warning easy to miss. He went this route because he doesn’t care to wear a bracelet or necklace to get caught on something or to accidentally fall off. Just another perspective.

—

I’ve never seen one, but I’m quite sure we’d notice it and appreciate the info! -rc

Thank you for making this episode. It got me thinking about a couple of conditions I have that, it not known, could result in damaging (or fatal) emergency treatment if I was not conscious or aware enough to provide information. I ordered my bracelet (and a wallet card as a backup) the next day (and now always have one or both on me when out of the house). I also put my MedicAlert ID number into my phone’s emergency contacts.

A note about the service levels. The MedicAlert Foundation has a premium level that allows you to upload documents such as a living will and medical power of attorney. As someone who has had to scramble to find those documents to be able to interface with medical professionals dealing with loved ones, having those documents always available online is a great relief.

—

Part of thinking is thinking ahead. Good for you. One thing concerns me, though: you “always have one or both on me when out of the house.” What’s the one place you’re most likely to have a medical emergency? Home. So ideally, wear the bracelet all the time. Even marrieds can’t count on a spouse being there (and having all the medical info at-hand) all the time. -rc

Good point. I do wear it when alone but am not a fan of bracelets or other things on my body so I often do not wear it when family is around (they all know where the bracelet sits when I am not wearing it).

—

As long as you’re aware of the risk, and clearly you are, then you can make the informed decision. -rc