In This Episode: The story of a man who wasn’t satisfied with mere success. He took Uncommon Sense to a new level in order to help others, yet refused to get rich from it.

032: “Give Me a Shot at It. I’m an Engineer”

Tweet

How to Subscribe and List of All Episodes

Show Notes

- Help Support Uncommon Sense — yes, $5 helps!

- The photos mentioned are included in the transcript below.

- Kaplan’s National Inventors Hall of Fame induction.

Transcript

I’d like to tell you the story of a man who wasn’t satisfied with mere success. He took Uncommon Sense to a new level in order to help others.

Welcome to Uncommon Sense. I’m Randy Cassingham.

Sheldon Kaplan got his degree in mechanical engineering from Northwestern University in 1962 and, like many engineers during that era, got a job with NASA. Hired by the Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland to design hardware for satellites, he moved to a contractor company in 1965, where he still worked on NASA projects. One of his first tasks was to design an emergency medical kit for the Apollo program.

The company had other government contracts too: he also designed something called the PneumoPak, a pressure dressing for high-altitude reconnaissance pilots. Starting to see the pattern here? Medical technology: Kaplan liked to be a part of saving lives by coming up with solutions that helped solve problems.

The company had another device that just wasn’t working out. It was called the AtroPen, designed to administer drugs in the field. To keep it rugged, the drug to be dispensed was held in a stainless steel capsule: that meant only drugs that could be kept stable in steel could be used, and there were other mechanical issues. Kaplan set upon completely redesigning the device from scratch — and figuring out how to use glass to hold the drugs: glass is the gold standard in injectable drug storage, which also enabled users to see the drug to ensure the right amount was there, or to see if it was discolored or cloudy.

Why was the device needed? In the 1950s, a new chemical weapon was starting to be developed: organophosphate nerve agents. There are a couple of antidotes for it, but obviously they must be administered pretty quickly to save the victim. That meant, for instance, that soldiers needed to carry the antidotes with them, and be able to inject themselves quickly should the antidote be needed, rather than wait for a medic to arrive to help. So the entire package had to be self-contained, stable over time, stay sterile until use, be relatively fool-proof, and be injectable through clothing. That’s a tall order, especially in battlefield conditions.

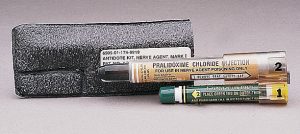

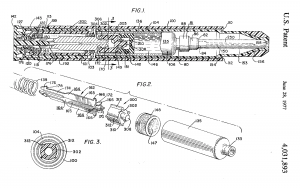

But when Kaplan was done, he met all of the objectives. It was called the ComboPen, because there were two auto-injectors, one for each of the drugs. The U.S. military called the package the Mark I NAAK, or Nerve Agent Antidote Kit, which is pictured on the Show Page. It works against nerve agents like Sarin and VX. Survival Technology received a patent on the device in mid-1977, with Kaplan shown as the lead inventor. The diagram of the thing is a study in complexity: I have that on the Show Page too.

But once that process was done and the contract satisfied, Kaplan had already realized there was another application for the auto-injector he invented: one that could have much wider application and save the lives of a much larger number of people. It may have already dawned on you what other drug needs to be delivered quickly from a package that is self-contained, stable over time, sterile until use, relatively fool-proof, and be injectable through clothing. That’s another tall order, especially for, say, kids, in playground conditions.

Epinephrine, otherwise known as adrenaline, is the emergency antidote for anaphylaxis, or the out-of-control allergic reaction that develops in at least two percent of the population. Anaphylaxis sets in quickly, leads to shock, and rapidly becomes life-threatening when airways start to swell and cut off breathing. Even the 5-10 minutes it takes for an ambulance to arrive could well be too long.

So Kaplan re-purposed that same device that he developed to save soldiers from nerve gas to something much more civilian in nature: the EpiPen — the Epi being short for epinephrine. In about a third of cases where the EpiPen is used, the reaction is bad enough that a second dose is needed. By the time it’s needed, it’s pretty likely an ambulance can be there with more epinephrine to give a second dose. Some who know they have particularly severe reactions will often carry two doses themselves.

Kaplan, who liked to invent medical devices to help save lives, looked beyond his assignment for the military. Rather than just find a solution to one specific problem, he applied Uncommon Sense to his job to extend the solution he came up with to another pressing problem — one that certainly has a lot more victims to save on a day-to-day basis. Kaplan’s EpiPen was approved by the FDA in 1987, and has since saved countless lives: millions and millions have been sold. And when you look at the EpiPen that was used through the rest of the 20th century and beyond next to a Mark I nerve agent kit, you can see the two devices are essentially identical, other than the drug inside.

“Shel was proud to know that his invention had affected tens of millions of people, had kept them alive,” said Kaplan’s wife, Sheila, after his death in 2009 from liver cancer, at age 70. She says that on their third or fourth date, when she was 24 and he was 30, she and Sheldon talked about their life goals. “I want to do something that’s going to leave the world a better place than when I got here,” he had told her. “Being an engineer working in medical products, I think I can do that.”

And, Sheila said, “He really did accomplish what he wanted to do.”

Once Kaplan finished that work, he left Survival Technology to work at other companies that let him continue to develop medical devices. He eventually retired to Florida and, the Tampa Bay Times noted, he “died in obscurity.”

“He was very analytical but also very creative,” said his son, Michael. “He could deconstruct and fix any problem if he understood the mechanics. ‘Give me a shot at it,’ he’d say. ‘I’m an engineer.’”

So what is someone like Kaplan like? “He was not ego driven,” Michael says. “He didn’t spend time trying to figure out how to do things that were flashy or that would make him famous. Every day he was committed to solving important problems that no one else could.”

And indeed Kaplan wasn’t famous, though in 2016, well after he died, Kaplan was inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame. He didn’t get rich, either: Survival Technology owned the patent, and the EpiPen has bought out by company after company over time. “He was not wealthy,” confirmed his son Michael, who ought to know. “And,” he continues, “I don’t think he would’ve liked to be. I don’t think he expected that.”

Yet the device Kaplan invented for the government is now being used to make money for someone else. A drug company called Mylan bought the rights to the EpiPen in 2007, and they have been relentlessly boosting the price to squeeze money out of insurance companies who are pretty much obligated to pay for this lifesaving device. What was well under $100 for a two-pack in 2007 now costs as much as $700, and Mylan has been clever in marketing, even lobbying Congress to pass a law requiring schools to have them on hand. By 2015 their sales reached $1.5 billion per year, accounting for 40 percent of the company’s profits. All for a device that delivers a drug that costs about a dollar, and was funded by taxpayers.

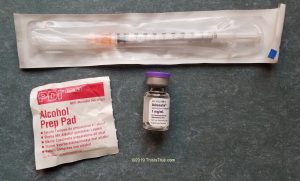

Ironically, the cost is now so high that ambulances are more and more carrying plain syringes and vials of epi to administer the drug, just as was used in the old days before the EpiPen. It’s not all that difficult to train someone to use a plain syringe, just like insulin-dependent diabetics do several times per day. It’s how I, as a medic in my rural community, carry it: I’ll put a photo of that on the Show Page too. It’s slower to use than an EpiPen, but in addition to the massive cost savings, the vial and syringe system allows for multiple doses to be given if needed: a tiny vial holds about three adult doses.

And no doubt, Sheldon Kaplan would have just shaken his head in amazement.

Meanwhile, military personnel going into areas where nerve agents are considered a hazard are still issued autoinjectors, though Kaplan’s original design has since been updated to deliver both antidotes in one shot, one right after another. But even with that improvement, you can bet the government doesn’t pay several hundred dollars apiece for them! Because after all, American taxpayers paid for it all up front.

Just a quick note that I’ll be on travel again next week for a class, and there won’t be a new episode next week.

For links and photos related to this episode, the Show Page is thisistrue.com/podcast32, where you can also comment.

I’m Randy Cassingham … and I’ll talk at you later.

– – –

Bad link? Broken image? Other problem on this page? Use the Help button lower right, and thanks.

This page is an example of my style of “Thought-Provoking Entertainment”. This is True is an email newsletter that uses “weird news” as a vehicle to explore the human condition in an entertaining way. If that sounds good, click here to open a subscribe form.

To really support This is True, you’re invited to sign up for a subscription to the much-expanded “Premium” edition:

Q: Why would I want to pay more than the minimum rate?

A: To support the publication to help it thrive and stay online: this kind of support means less future need for price increases (and smaller increases when they do happen), which enables more people to upgrade. This option was requested by existing Premium subscribers.

“Give Me a Shot at It. I’m an Engineer”

I know the feeling. If somebody made it, I can fix it…as long as I have the right tools. Sometimes it costs more than buying new, maybe, but where’s the fun in that?

I carried the NAAK for years in the Army. Everyone was scared of the delivery system, it had/has a rather large needle. And don’t be fooled by the scene in “The Rock” where Nicolas Cage injects himself with the NAAK. While equipped with a heavy duty spring and one heck of a needle it still isn’t punching through a breast bone.

It’s absolutely dreadful how the prices of drugs have been raised to outrageous levels for lifesaving drugs. I don’t blame the many states who are suing the generic drug industry for price raises beyond all sense, common or otherwise — my husband told me yesterday, after reading a story about the prices of generic drugs, that in the last ten years prices have gone up 14,000%.

Something needs to be done. When people’s lives are at risk, there is no excuse for corporate greed to price drugs out of their reach. I know many insulin-dependent diabetics are rationing their insulin or even skipping doses simply because the drug has gotten so expensive, and that is just one out of MANY examples. We all need to get behind the investigation into this corporate greed and find ways to resolve it or the work of inventors like Sheldon Kaplan will, in the end, be all for naught.

Spot on. But I doubt anything will be done until a politician’s family is directly impacted.

The problem is, if it does affect a politician’s family they have the best of the best healthcare so they can afford it. Paid by YOUR tax dollars of course.

Greed is the issue.

EpiPens, Insulin, Glucagon (for us hypoglycemics) and albuterol Inhalers should be really cheap as they’ve been around for years.

I suspect that’s a big part of the reason that health care is so expensive in this Land of the Not-So-Free. It’s not just Big Pharma that scores big profits. When my wife was in the hospital to deliver our daughter in 1991, the hospital charged my insurance $200 for four Tylenol. Fifty dollars a pill. It seems that the problem is driven by the requirement to provide emergency medical treatment even for the indigent. So they make up the cost by passing it on to everyone else.

I am told it helps to ask/insist on an itemized bill, especially when you have out-of-pocket for whatever reason. Gonna try that next time.

My son used to get on my case for “spending more time and money coming up with something new than it would have taken to do it the old way.” But I’m right with Jeff in Georgia … where’s the fun in that? I also independently re-invented rack and pinion steering and a few other knick-knacks. Now I’m working on a baby seat to put babies to sleep as if they were driving around in a car. 🙂

I’m grateful I don’t need an EpiPen, but if I did, I would make it a point to somehow not buy them from the gougers. Making yourself rich by hurting others is immoral.

In many ways, he was a normal engineer. It is very simple to know if someone is a good engineer, or will be: if they wake up every day wanting to make a positive impact on the world.

Remember when trickle down voodoo economics taught America that “greed is good”. Isn’t it inspiring how far we have come?

I deal with the issue of drug prices every day in my job working for a Medicare/Medicaid management company’s assistance line. We’re not allowed to get political with clients, but here I can express my disgust with the appointment of Alex Azar as head of the United States Secretary of Health and Human Services. Previously, Azar worked for Eli Lilly, and prices for drugs rose substantially under Azar’s leadership. Azar made millions raising drug prices, and now he’s supposed to protect consumers? Bah, humbug!

Another reason why the US should finally join the rest of the western world in installing a general health insurance system. It’s just common sense. Human health is too important to leave to the whims of the free market.

People around the world are shocked to see the injustice and cruelty of the US health system, to see the acceptance of ordinary Americains to quietly pay fortunes for simple medicines, allowing smart bussinessmen to become billionaires.

No, I’m not some crazy communist, leftwing radical. I vote middle of the road politics and as an engineer I believe government is about solving problems, sensibly.

So it’s about time you guys start voting the engineers into power and vote out the people who don’t know what they’re talking about. It’s time for the Kaplan’s of this world to become state and federal health authorities.

A couple of points to make…

1. Even if the US “followed” the rest of the world, medication is not covered in the “free” health care system. Here in Canada, I still have to pay for prescriptions separately from my taxes. I pay for health insurance to cover my prescriptions. And the meds are not cheap.

2. Most engineers are not interested in politics or making policy. It isn’t interesting enough, or there is too much red tape to do anything. The bureaucratic systems work against them. Also, politics is too poisonous. In today’s political world, your opponent (or their agents) would do nothing to destroy you and your career, or even the company you work for.

I’m speaking from experience on all the stated comments above. I’ve lived in the US, I’m an engineer, been attacked, and tried politics.

I believe you meant to say, “In today’s political world, your opponent… would do anything to destroy you…”.

Yup, correct.

My kid used to carry an epinephrine injector called “Twinject” which was smaller than an EpiPen and allowed a second (albeit fiddly) injection from the same device. Unfortunately these were discontinued with no explanation.

—

I remember the Twinject. It came out in 2003 — four years before Mylan bought out the rights to EpiPen. The company that made it was bought out by Verus Pharmaceuticals, which sold the Twinject brand to Sciele Pharma …which was then acquired by Shionogi. The device apparently couldn’t survive the EpiPen mass marketing. -rc

Why on EARTH would you turn to the government that created the problem for a solution to it?

How can a company charge $700 for an EpiPen? Because they have a monopoly on the product. With no competition, they can do anything they want with it.

How can the company that makes EpiPen have a monopoly on it? Because the government created the legal environment that blocks others from competing with it.

What would happen if the government did not maintain a monopoly for the company that makes EpiPen? Lots of companies would make them and the prices would drop dramatically.

How is it the company that makes EpiPen can have exclusive rights to a product whose patent is over 70 years old? Corrupt government passes legislation enabling it to choose the winners and losers instead of the free marketplace allowing consumers to vote with their dollars.

—

“EpiPen” is a registered trademark, so yes: they’re the only ones that can use that brand. But indeed other companies can — and have — made their own autoinjectors based on the expired patents. And then they get to compete against Mylan, with its huge marketing war chest. -rc

Presumably AtroPen gets its name because it’s a device that administers Atropine, the standard treatment for organophosphate poisoning.

—

Correct. I used to carry atropine as a cardiac drug, but we also trained with it for organophosphates — though we anticipated insecticide exposure, not nerve agents, as the vector. Thankfully, never needed it for that (but did use it in heart cases). -rc

Drug companies should be seized by eminent domain and their assets sold or leased to companies that contract to provide drugs at reasonable costs.

This would be entirely legal according to the Supreme Court: “Kelo v. City of New London, 545 U.S. 469, was a case decided by the Supreme Court of the United States involving the use of eminent domain to transfer land from one private owner to another private owner to further economic development.”

Taking private property (with compensation) for the public good is the law of the land.

The problem with taking private property under Eminent Domain is that there will be no guarantees that the property won’t then be turned over to the “proper” people or companies (i.e. the one’s with the largest contributions to some politician’s campaign — but you didn’t really read that).

There are no guarantees. Except that under the current situation, things will not get better.

I just looked it up, and patents EXPIRE after 20 years. According to the article, the FDA approved the EpiPen in 1987, which means the patent expired no later than 2007. Earlier, if the patent pre-dated the FDA approval.

Doesn’t this mean that after 2007, ANYONE can make Epi-Pens (or variations of them, such as for NarCan) without worrying about patents by greedy corporate moneygrubbers?

—

Anyone can make epipens, though of course you noticed how I pointed out that the design had changed? That’s to get a new patent. So others can make “old” epipens, and then fight the money-laden juggernaut that has something “better” to offer. Oh, and they can’t call it an “epipen” — that’s a registered trademark. Bottom line: it’s tough for a newcomer to break into the market. -rc