In This Episode: Why isn’t there more Uncommon Sense?

Because the default for humans is to resist change. Uncommon Sense requires your mind to be open to new ideas, to be convinced that “the way we’ve always done it” might not be the best way. Yet humans resist change even when sick and dying, and the change might save their lives. Don’t believe me? Then you haven’t heard this story.

How to Subscribe and List of All Episodes

Show Notes

- Help Support Uncommon Sense — yes, $5 helps!

- Note: This is the first of three episodes on innovation. They don’t need to be listened to in order. Part 2 is 056: Running with An Idea, and Part 3 is 057: The Key to Innovation.

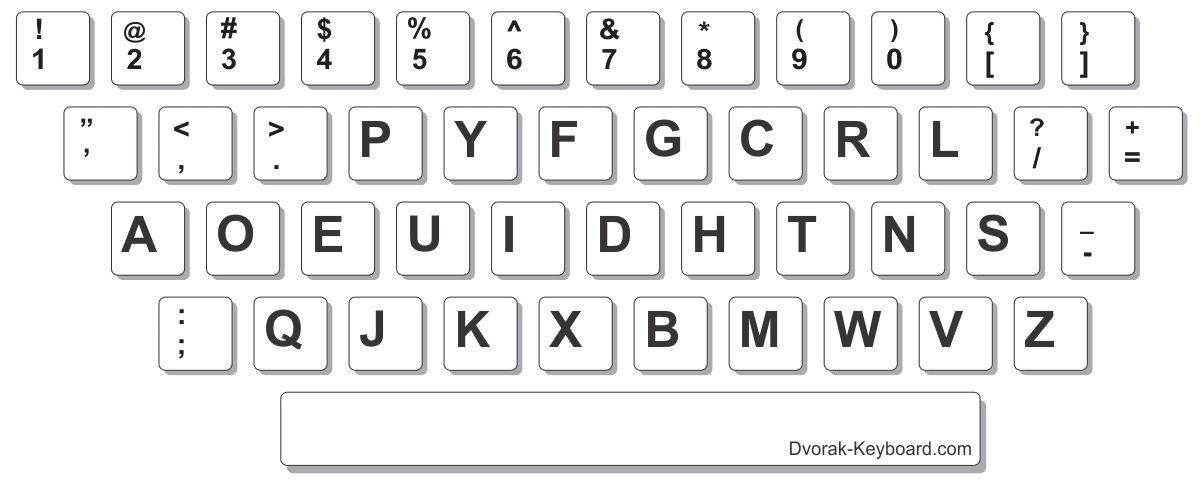

- A diagram of the Dvorak keyboard layout is below. My web site is Dvorak-Keyboard.com.

- If you want to try Dvorak yourself, see my page on converting your computer (don’t worry: it’s easily reversible).

Transcript

Why isn’t there more Uncommon Sense? Because the default for humans is to resist change. Uncommon Sense requires your mind to be open to new ideas, to be convinced that “the way we’ve always done it” might not be the best way. Yet humans resist change even when sick and dying, and the change might save their lives. Don’t believe me? Then you haven’t heard this story.

Welcome to Uncommon Sense, I’m Randy Cassingham.

The first book I wrote was about the Dvorak keyboard, a typing layout that’s easier to learn and use: I went from about 55 words per minute on Qwerty, the layout that you almost certainly use, to 120 words per minute on Dvorak; more than double the speed with fewer errors. For a full-time writer, that represents a huge productivity boost. The book came out in 1986, and is currently out of print. I’ve wanted to publish an updated edition, but it’s not the highest priority on my list. Maybe someday.

Anyway, one of the things I studied back then was about why, if Dvorak is so superior — and I do still believe it is — why hasn’t it caught on more than it has? Though it is used more than a lot of people think. I remember when I first moved to Colorado, a reader who lived in Boulder invited me to lunch. He had me come to his office, and I arrived a little early. He wasn’t quite done with what he needed to finish before lunch, so I took a seat to wait.

I was looking around his office and the interesting things he had on display, but something jerked my attention back to him: it was the way he was typing. His hands were not jumping all over the keyboard. I couldn’t help but interrupt him: “Do you use the Dvorak keyboard?” I asked. Yes, he replied: that’s how he had first learned of my work — from my Dvorak book — and he decided it made sense and he switched immediately. I had never considered the possibility that it might be easy to tell that someone used Dvorak just by the way they were typing, but it makes sense in retrospect.

The concept here is why apparently proven innovations sometimes don’t catch on, no matter the possible benefits. And it’s not just random people who ignore improvements, but people of science, too.

Take, for instance, the ailment called Moeller’s disease, named for Prussian physician Julius Otto Ludwig Möller, who in the 1800s described the symptoms of a baffling malady. The thing is, it was previously called Cheadle’s disease, named for English physician Walter Butler Cheadle, who in the 1800s described the symptoms of a baffling malady. And there was Sir Thomas Barlow, another English physician who found a similar disease in infants.

But none of those doctors were first. Pliny the Elder of ancient Rome identified it around the year 50. Strabo, an ancient Greek physician, described it about 50 years before that. Hippocrates, the ancient Greek father of medicine, the namesake of the Hippocratic Oath, identified it in around 400 B.C.

He wasn’t first either. It was also described by the ancient Egyptians as far back as 1550 B.C. And many, many, others have “discovered” the disease over the centuries.

The disease starts with weakness, and sore arms and legs. Unless treated, it leads to a decrease of red blood cells, gum disease, changes to hair, and bleeding from the skin. As it progresses, there can be poor wound healing, personality changes, and, eventually, death from infection or bleeding. It ain’t pretty. In the 1700s, more British sailors died from this disease than from anything else, including war injuries. To say it was a priority for doctors to figure out would be a gross understatement.

It’s still with us today, though it’s very easily treatable: we call it scurvy.

Scurvy has been identified, cataloged, and cured many, many times …and then doctors forget about it, and later it pops up again, and is a mystery again.

It’s caused by a lack of Vitamin C in the diet, and the British Navy had a real problem with it, since early sailing vessels couldn’t carry enough fresh food for sailors to eat: it would rot before long, so the Navy needed food that would keep for a long time, and this is long before refrigeration. Vitamin C is easily destroyed in food, and preservatives and drying can leave a food with no Vitamin C left at all.

The most common cure they discovered was simply eating fresh citrus or its juice, which as we know today is a good source of Vitamin C.

In 1601, a British sea captain who commanded four ships on a voyage to India tried an experiment. On his own flagship, he gave each of his men three teaspoons of lemon juice every day, and most of the men on his ship stayed healthy. But nearly 40 percent of the men from the other three ships died from scurvy. The results were so clear cut that James Lind, a Scottish surgeon, tried a similar experiment, considered one of the first controlled medical trials, in 1747 — nearly 150 years later …though he didn’t publish his results until 1753. The Royal Navy then ordered that all sailors be served lemon juice to prevent scurvy — in 1799, 46 years after that. And in 1865, 70 years after that, the British Board of Trade adopted a similar policy, finally also eliminating scurvy in the British Merchant Marine.

The British, by the way, for economic reasons, later settled on lime juice, and that’s the origin for the mid-1800s nickname of the British people, especially sailors, that you still occasionally hear today: limeys.

The bottom line: it took the British about 200 years to fully accept this simple cure for a horrible disease. How many tens of thousands of sailors died a terrible death along the way?

Yet the simple cure for scurvy was forgotten again, even during the British Antarctic Expedition, which took place between 1910 and 1913. Apsley Cherry-Garrard, one of the youngest members of the expedition, was acclaimed for his book about the trip called “The Worst Journey in the World”. In that book, he mentions the expedition’s surgeon, Edward Atkinson of the Royal Navy:

Atkinson inclined to Almroth Wright’s theory that scurvy is due to an acid intoxication of the blood caused by bacteria…. We had, at Cape Evans, a salt of sodium to be used to alkalize the blood as an experiment, if necessity arose. Darkness, cold, and hard work are in Atkinson’s opinion important causes of scurvy.

So there we are, in 1911, and a renowned Royal Navy surgeon had no idea what caused, or prevented, scurvy, despite centuries of experimentation to successfully find the preventative and cure.

This sort of mental exercise — why it takes so long for good ideas to be adopted — was a specialty of Professor Everett M. Rogers, a communications theorist who wrote a book about it called Diffusion of Innovations, first published in 1962, with revisions published through 2003 (Dr. Rogers died in 2004).

To study diffusion, or the spreading of an idea among the people that will make use of it, researchers like Dr. Rogers analyze the way that innovations spread — some very slowly, some very quickly. And Dr. Rogers used the Dvorak keyboard as a case in point. He noted the Qwerty layout persists even though “a much more efficient typewriter keyboard is available.” He sketched out Qwerty’s genesis in 1873 as an “anti-engineered” solution to the mechanical problems of early typewriters, and how dissatisfaction with the Qwerty keyboard grew with the advent of touch typing in the early 1900s. But, even today, it’s still the most widely used keyboard in the world.

Dr. Rogers wrote in the 1982 edition of his book that “One might expect, on the basis of its overwhelming advantages, that the Dvorak keyboard would have completely replaced the inferior Qwerty keyboard by now.” But even with the adoption of the Dvorak as an “alternate” layout to Qwerty by the American National Standards Institute in 1982, Dvorak is still used by relatively few of what he called “early adopters” — a term he coined. “Technological innovations are not always diffused and adopted rapidly,” he said, “Even when the innovation has obvious and proven advantages.”

So when some innovation is not adopted, it doesn’t mean it was a bad idea. As I said at the start, the default for humans is to resist change, no matter how good an idea that change might be. As you’ve gathered by now, that’s been the case for a long, long time. Other social commentators have taken note of it over the centuries, and published their thoughts on the idea. One particularly telling example was by Benjamin Franklin in 1781. He wrote:

To get the bad customs of a country changed and new ones, though better, introduced, it is necessary first to remove the prejudices of the people, enlighten their ignorance, and convince them that their interests will be promoted by the proposed changes; and this is not the work of a day.”

Ain’t that the truth.

So you can see why I think common sense is very often not enough. To be open minded enough to change the way things are done usually takes Uncommon Sense. And sadly, it’s much more rare than simple common sense, and you know how rare that is!

By the way, yes: I still use the Dvorak keyboard. And you know what? After I met Kit and she saw the advantages I was getting from using Dvorak, she switched to use it too. That demonstration of her Uncommon Sense early in our relationship is just one of the reasons I decided to marry her.

For a diagram of the Dvorak layout, a link to my Dvorak web site, a transcript of this episode, and a place to comment, see the Show Page at thisistrue.com/podcast55.

As always, I need your help to keep the podcast going: contributions are why there are no commercials interrupting the episodes — and no ads on the web site. There’s info on how to help on the Show Page.

I’m Randy Cassingham … and I’ll talk at you later.

– – –

Bad link? Broken image? Other problem on this page? Use the Help button lower right, and thanks.

This page is an example of my style of “Thought-Provoking Entertainment”. This is True is an email newsletter that uses “weird news” as a vehicle to explore the human condition in an entertaining way. If that sounds good, click here to open a subscribe form.

To really support This is True, you’re invited to sign up for a subscription to the much-expanded “Premium” edition:

Q: Why would I want to pay more than the minimum rate?

A: To support the publication to help it thrive and stay online: this kind of support means less future need for price increases (and smaller increases when they do happen), which enables more people to upgrade. This option was requested by existing Premium subscribers.

Many years ago, in the 80s, all of the support staff from my company was invited to a demonstration of the Dvorak keyboard. I was interested, but ultimately, I had to stay at the office with my boss. All of the others went and upon their return, all agreed the new design was better and faster. The office never changed over, so to this day, I have no experience or hands on with it. I’m willing to try, but I never see a laptop with a Dvorak keyboard.

—

Dvorak is built in to Windows (and MacOS). This page on my Dvorak site has details. -rc

Of course the biggest reason people don’t switch over would be not being able to switch everything in the entire office. If the company insists on standard keyboard so anyone in the company can use it, it’s HARD to switch at home, get comfortable with it, and then have to switch BACK every day when going to work. Talk about a mind-blowing experience! And, of course, if you work for the government, that will never change in the next 1000 years — talk about your inertia! (Lots of part-time temporary work with the upcoming 2020 census).

—

I used Dvorak in my NASA office. It was considered improper to use someone else’s computer without permission. If I did want to let them use them (I had a Windows machine and a Mac), I could easily get Qwerty for them with a few clicks. -rc

This site has a longer article about scurvy and the 1911 expedition.

—

Excellent info, with a lot of detail! -rc

I’m running Windows 10, and there is no “Control Panel’ listing. When I go to “Settings,” then to “Time & Language” I get “Windows Language” & “Preferred Language.” None of that leads me to a input for the keyboard.

Any ideas would be helpful.

—

I’m guessing you mean Windows 10 Home. I always pay a bit more for the “Pro” version of Windows, so I can’t step through it on my machine to describe to you how to do it if and when it’s different on “Home”. I’m aware that W10 uses “apps” to do a lot of things rather than “programs” — and frankly I have that “App” screen turned off because it gets in my way.

That said, when I run the “Settings” app and type “Language” in the “Find a Setting” box, I get here, which I think is where you are:

I’m not changing the “Windows display language” — I need that in English! — so you click in that lower spot, which is what your current settings are. That brings you here:

So what you’re doing is literally adding the “United States-Dvorak” keyboard. I actually remove the Qwerty because I never use it. There are keyboard shortcuts to switch between the two (as well as an on-screen icon in the notification area, which when clicked allow you to switch to the one you want), and I never want to accidentally end up in Qwerty; no one else uses my computer. Note that for each window/program you open, the default is what you’ve set as default, which is probably Qwerty, so you’ll need to individually switch them to Dvorak if you want to play with it. -rc

I just tried this and clicked on (US) Dvorak and nothing happened. My typing is still in QWERTY and it did not seem to add Dvorak. Why not? If it does add Dvorak, will I just have to remember the keys for Dvorak because the letter I am typing is on each key? Thanks.

—

See the note on the conversion page of my Dvorak site: Windows programmers chose to make the conversion per window (or program), not “the whole computer.” Adding Dvorak to your options is just one step; then you need to choose it for the program you’re on (there “should” be a little icon on the bottom notification bar). To get Dvorak all the time, you’ll need to set it as the default.

As far as the letters on the keys: ideally you never look at them anyway. Dvorak is so perfect for touch typing, you’ll never get fast if you have to look at the keys. You can get stickers for the “fooling around” stage, but if you’re actually going to do it, learn it by touch to start with, and you’ll learn faster and better. -rc