In This Episode: What if you have a business idea, but you’re not sure if you want to take the risk to pursue it: should you quit your day job? Well, there’s an alternative to quitting your job, and it’s something a lot of people with Uncommon Sense are doing instead: they’re getting their employers to back their innovative ideas.

056: Running with An Idea

Tweet

How to Subscribe and List of All Episodes

Show Notes

- Help Support Uncommon Sense — yes, $5 helps!

- Note: This is the second of three episodes on innovation. They don’t need to be listened to in order. Part 1 is 055: Resisting Uncommon Sense, and Part 3 is 057: The Key to Innovation.

- The 1985 Newsweek article I mentioned is [Steve] Jobs Talks About His Rise and Fall, and the Forbes article mentioned is Looking For Purpose At Work? Be An Intrapreneur.

- The Uncommon Sense episode about Reynold Johnson is 004: Full Circle.

- The book mentioned: Kaihan Krippendorff’s Driving Innovation From Within *.

Transcript

I’m Randy Cassingham, welcome to Uncommon Sense.

A few generations ago the classic job profile was to work for a company for 20 or 30 years and, when you reached 65 you’d get a retirement party, a gold watch, and a pension to live on for the rest of your life, which statistically might have been 5 or 10 years. It’s increasingly hard for the average person to find such a job anymore, let alone get hired into such a position.

These days, we’re much more likely to work past age 65 either because we have to in order to survive, or because we like our jobs so much we want to continue to have fun. The latter at least seems more and more rare.

So it’s no wonder that entrepreneurship — working for yourself — is quite attractive. But this episode actually isn’t about entrepreneurship. Rather, it’s about intrapreneurship, which sounds like a brand new fad, but it isn’t: the term was coined by business author Gifford Pinchot and his wife Libba in a 1978 whitepaper, and then expanded in a more popular article in 1980. The couple created a consulting business around the idea, not surprisingly at intrapreneur.com.

While they may have coined the term in the late 1970s, the idea goes way back. But first, what is it? According to the American Heritage dictionary, an intrepreneur is “A person within a large corporation who takes direct responsibility for turning an idea into a profitable finished product through assertive risk taking and innovation.”

For an example, days after Apple Computer co-founder Steve Jobs left the company in late 1985, he was interviewed by Newsweek magazine and said this:

The Macintosh team was what is commonly known now as intrapreneurship — only a few years before the term was coined — a group of people going in essence back to the garage, but in a large company.

Jobs and Steve Wozniak founded Apple Computer in a garage in what’s now known as Silicon Valley, following in the footsteps of their model, Hewlett-Packard.

I say the idea goes way back because “intrapreneur” beautifully describes Reynold Johnson, the subject of Episode 4 of this podcast. I’ll link to that episode on the Show Page. While he certainly wasn’t the first either, IBM president Thomas Watson Sr. set him loose in his own research lab in January 1952, and Watson specifically wanted Johnson to establish that lab far away from IBM headquarters to be independent of IBM managers’ constant oversight. He set it up in San Jose, California — in what’s now known as Silicon Valley.

Krippendorff told Eisenberg that, for his book, he “interviewed a hundred and fifty internal innovators and I’d say more than half of them are above fifty. They have a lot of institutional knowledge and business relationships and they understand the political dynamics that can guide them through their organization.”

Of course, that also means than nearly half are under 50, so the idea is clearly not related to age.

He goes on to say that such intrapreneurs are “not typically motivated by money.” Instead, “the prolific ones recognize they didn’t have to eat ramen noodles and put their children’s financial future at risk” by becoming entrepreneurs. “They enjoy being an innovator because it’s fun or because of the impact they have.” Krippendorff says such corporate employees “look like they’re risk takers, but they’re creating risk-asymmetric situations where the company bets a little with the potential to benefit a lot. They’re not playing with their money, but with the company’s money.”

Though I’ll observe that they rarely get a share of the long-term profits when they get a home run for the company with their ideas. Well, I guess that’s why he says they’re “not typically motivated by money.”

Yet here’s the rub. Krippendorff notes that “I think every company will say they love people to be more entrepreneurial and encourage internal entrepreneurs. But cultural norms and structural things at companies discourage it.” Still, he says, “the trend is toward encouraging greater internal innovation.”

The way I take that: companies want the innovations, but they’re reluctant to give up control. To me, that means that intrapreneurs have to be pretty bold mavericks to make such a team happen. Or, as the definition puts it, “assertive risk taking.” Steve Jobs was enough of a maverick himself to let his Macintosh team have some pretty free reign.

The reason I think Krippendorff has such a bifurcated stance on this idea is that, he admits, he chose the companies he studied from “the Fortune and Forbes most innovative lists over the last five years.” So it’s not just any company that truly embraces this sort of innovation, even if they’d like to be seen that way, but the companies that are already recognized as the most innovative are clearly more likely to foster such internal entrepreneurs, or intrapreneurs.

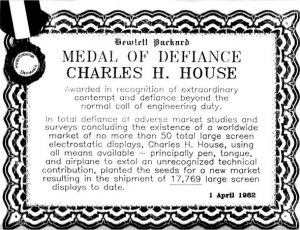

Krippendorff gives an example of another early intrapreneur, an engineer at Hewlett-Packard in the 1960s. Chuck House was working on large computer monitors, which on the surface didn’t seem like a great idea in the mainframe computer age. He says company co-founder David Packard stopped by House’s lab to see what was going on there, and hated the idea. He is said to have told House, “I don’t want to see it when I come back next year.”

House didn’t see that as a veto of his idea, but rather that he needed to get his idea on the market within the next year! “So,” Krippendorff continues, “he worked on it on his own time, took prototypes to customers and came back with orders. Because he did this, we got to see Neil Armstrong land on the moon.”

See what I mean by mavericks?

David Packard wasn’t a sore loser: he understood that House’s defiance was responsible for a lot of sales. So he awarded House a “medal of defiance,” to recognize his “extraordinary contempt and defiance beyond the normal call of engineering duty.”

Krippendorff thinks intrapreneurs have an advantage over entrepreneurs because they don’t have to raise money to hire teams, they can often choose from internal employees that they already know, and are already being paid.

“It’s tough to find an idea your company loves,” Krippendorff says, “but once you do, it scales very quickly.” He says would-be intrapreneurs shouldn’t just take every idea to their boss in hopes of a go-ahead, because “Organizations are rarely able to deal with ideas that carry uncertainty.” Thus, he says, they should validate their idea by, for instance, doing market research or building what entrepreneurs call a “minimum viable product” — a prototype that they can show to real-world customers to see what they think, and maybe can buy right away while the team goes back to improve it.

As an entrepreneur myself, I know the challenges of working essentially by yourself. If you don’t want to execute an idea yourself by quitting your day job and taking all the risk, you may not have to quit your day job. As you might have gathered, I think that’s a truly Uncommon Sense way to try something new, without fully letting go of whatever security your current job offers.

In the next episode I’m going to talk about the nature of innovation, and what it really takes to be innovative as an entrepreneur or an intrapreneur — or, for that matter, as an artist, writer, actor, or any other creative type.

For links to my sources and a place to comment, the Show Page for this episode is thisistrue.com/podcast56.

I’m Randy Cassingham … and I’ll talk at you later.

– – –

Bad link? Broken image? Other problem on this page? Use the Help button lower right, and thanks.

This page is an example of my style of “Thought-Provoking Entertainment”. This is True is an email newsletter that uses “weird news” as a vehicle to explore the human condition in an entertaining way. If that sounds good, click here to open a subscribe form.

To really support This is True, you’re invited to sign up for a subscription to the much-expanded “Premium” edition:

Q: Why would I want to pay more than the minimum rate?

A: To support the publication to help it thrive and stay online: this kind of support means less future need for price increases (and smaller increases when they do happen), which enables more people to upgrade. This option was requested by existing Premium subscribers.