In This Episode: When sizing up someone in a modest profession, don’t make the mistake of thinking the job title defines the person or their abilities. They might just surprise you with an overabundance of Uncommon Sense.

004: Full Circle

Tweet

How to Subscribe and List of All Episodes

Show Notes

- To help support Uncommon Sense, see the Patron’s Page, or the form in the sidebar.

- A brief bio of Reynold Johnson published by the IEEE Computer Society, when he was given 1987’s Computer Pioneer Award for RAMAC.

- See several more photos, below.

Transcript

Way back in 1998, when the Honorary Unsubscribe first got started, they were very brief writeups, capturing just a few well-known features of the honorees’ lives. Actor Jack Lord, for instance, the first Honorary Unsubscribe honoree — his writeup just mentions “various films” and then the role that made him a star: “Steve McGarrett” in 12 years of the TV series Hawaii Five-O. That took less that 50 words, including the date and cause of death!

But there’s another guy that has always stuck in my mind, even though I summed up his life later that same year in just 118 words. You’ll soon understand why I’ve remembered him for 20 years now. As I thought about him recently, I wanted to know what brought him to the place where he was — a place that made him stand out even with the few details I knew that led to my answer anytime someone asked me which of more than one thousand Honorary Unsubscribe honorees stand out for me the most.

And that would be Reynold Johnson, or Rey to his friends.

Rather than read you that way-too-terse summary from 1998, I decided to research him more fully so I could understand how he got to where he was and, since I did that, take the opportunity to tell his story to the world more fully right here and now.

Born in Minnesota to Swedish immigrants, Johnson went to a private Christian school, perhaps for his entire 12 years of basic schooling, and he seems to have liked it: he then went to the University of Minnesota for his bachelor’s degree in Educational Administration, and became a high school science and math teacher in Ironwood on the western tip of the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, on the border with Wisconsin. Today, the town has about 5,000 residents.

At that time, there was a great new innovation in teaching developed by Benjamin Wood of Columbia University, something that totally changed the teaching profession. Let’s see if you can guess what Wood invented. Was it a) the intelligence test, b) standardized textbooks, c) recess, or d) the multiple-choice test? It seems weird to us today, because it seems so obvious now, but it was the multiple-choice test: he invented it in about 1929.

The problem Dr. Wood found, though, was it was time-consuming to score the tests. You’d think it would be easy compared to grading the hand-written answers to various questions, but remember we’re talking about mass education here: thousands of schools jumped on the multiple choice bandwagon, and something easier was needed for the scoring.

Wood appealed to many office machine companies for help, and only one responded: International Business Machines. IBM president Thomas J. Watson Sr. authorized company engineers to design a machine, which takes us on another tangent.

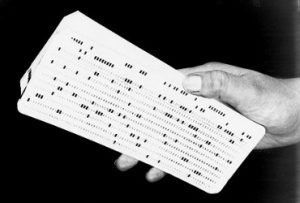

In the late 1800s, Herman Hollerith perfected something that was first invented in 1725 to record data by punching holes in a long ribbon of paper. Hollerith’s twist was to punch the holes in stiffer card stock. Hollerith cards or, more popularly, punch cards. They were first put into wide use for the 1890 census. To produce the machines to process data punched on his cards, Hollerith founded the Tabulating Machine Company in 1896. In turn, that company was merged with three others to form the Computing-Tabulating-Recording Company, or CTR in 1911, which in 1924 was renamed to something a little easier to say: International Business Machines, or IBM.

And what technology did IBM apply to the test scoring problem for Dr. Wood? The punched Hollerith card. By 1937 IBM was producing 5-10 million punch cards per day, so of course that was their solution. But it was ridiculous to think of putting a bunch of keypunch machines in schools all over the country for kids to take tests on.

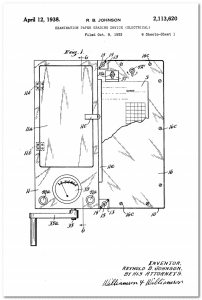

And that’s where we circle back to Reynold Johnson in little Ironwood, Michigan. He put his mind to the problem that he was having just like so many other teachers, and he came up with a better and cheaper solution. That’s right, a small-town high school teacher beat out IBM at their own game. Johnson’s system didn’t use punched cards. Instead, he came up with a simple paper form where kids could answer test questions by filling in little circles using a soft-leaded pencil — a number 2 pencil. And it’s almost sure that you’ve done just that many times yourself. Rey Johnson invented the system to record the answers and score them.

And where did he send his idea? To IBM! Yet after they showed Dr. Wood the description Johnson sent, company executives …rejected the solution! But Dr. Wood was friends with Thomas Watson, and called him to tell him his team made a huge mistake in rejecting Johnson’s idea. Watson not only stepped in and bought the rights to the entire system, he also hired Johnson to help to develop it into a workable machine that could be used by school systems everywhere. No one was more surprised than Johnson, who later said “I only thought of it as strictly a lazy teacher’s gimmick.”! IBM salesmen even warned Watson that the machine would never make money. Watson’s retort: “Who wants to make money out of education?”

That shows Watson’s own Uncommon Sense, and how short-sighted those salesmen were: there were a lot of other applications that could use such a system! For instance, my ballot for the midterm elections arrived in today’s mail. I’ll vote by filling in little circles, except the system was modified to use pen marks, not pencil, so it can be clear the vote hasn’t been altered by anyone.

You might be aware of Thomas Watson’s personal motto, which was spreading around IBM around that time: “Think.” He clearly understood the value of thinking, and his faith in Johnson paid massive dividends, and not just because the refined version of Johnson’s system, the IBM 805 Test Scoring Machine which they introduced to the world in 1936, sold so well in the 1930s. The descendants of that machine are still being used today!

Obviously, Johnson’s machine was a hit, and he continued working in IBM’s research lab, where he invented other things for the company. He did so well that in January 1952, Watson asked Johnson to do something truly radical: to open a research lab that was far enough away to be independent of IBM managers’ constant oversight, and where he was allowed to hire whatever researchers he wanted.

Johnson was asked to work on two different fronts: spend half time on “non-impact” printing, and half time on …anything else he wanted! Johnson went to San Jose, California — which you might now recognize as a major part of “Silicon Valley,” recruited engineers, leased and renovated a building, and was up and running by that July with a staff of 30.

One of the rules Johnson established for the lab was, it was considered a critical part of every engineer’s job to provide consultation and assistance to any other engineer in the lab when requested — an environment of cooperation, not competition.

Now remember that IBM was hugely invested in punched cards: it was the basis of a highly profitable business sector. The punched cards were stored in what they called “tub files” — huge trays with tens of thousands of cards that could be fed into early computers to analyze data. But imagine how slow that was: if you wanted to analyze the data they held, someone had to go to the tub files and pull out the specific cards needed by hand, and feed them into a computer, which itself would take some time. An IBM salesman in San Francisco took Johnson’s researchers into the field where they could see customers using this system and fully understand how inadequate it was.

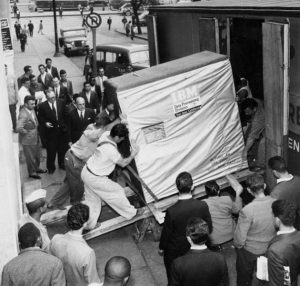

By January 1953, just a year after Johnson was assigned to head west, and only six months after he assembled his team, he was highly focused on a specific solution to that problem. And what he and his team came up with was a major leap in innovation. They called it RAMAC, or the “Random Access Method of Accounting Control.” And what the heck was that? A stack of spinning disks coated with the same sort of material used in magnetic tape, but — thanks to the disks spinning around and read/write heads that moved back and forth on a thin cushion of air, it didn’t have to unwind the whole reel of tape to get something at the other end.

Does that sound somehow familiar? That’s right: Johnson invented the hard disk drive. That first RAMAC system could hold and process an incredible 5 megabytes of information or, as IBM put it, the equivalent of 64,000 punch cards! To make it even more efficient, RAMAC had another innovation: buffer memory. It was a modest start: the buffer was just 100 characters. The unit meanwhile was huge and weighed nearly a ton — see the Show Page for a photo of the first one being shipped out to the U.S. Navy.

But IBM actually kept RAMAC a secret at first; by the time they announced it to commercial customers in September 1956, they had already installed several RAMACS for the military. The first commercial unit sold, in 1957, was to automaker Chrysler, who put it into its MOPAR division — their parts subsidiary — to keep track of inventory so they could order parts in when needed, rather than when they realized they were running out of something. And by the way, IBM didn’t sell the RAMAC, it leased it — for $35,000… per year. $35,000 in 1956 is the equivalent to more than $322,000 today, but it was worth it to buyers because it saved them so much more in more efficient data processing.

Just those two inventions would constitute huge success for anyone’s career, but Johnson was far from being tapped out. In the 1960s, he was working with Sony, and observed how hard it was to thread videotape into a machine for playback. Johnson, looking at that with the eyes of a schoolteacher, thought it would be too hard for kids to possibly do that, and thought if it was easier, it could lead to “video textbooks.”

So he first cut the one-inch tape down to a half inch, since that would allow high enough quality, and then packaged it all into a cartridge that could self-thread into the playback machine. Which means Johnson invented the videocassette, too.

By the time he retired from IBM in 1971, Johnson held more than 90 patents, and after his retirement, he kept inventing, including the microphonograph used in Fisher-Price’s “Talk to Me Books” — which went on to win the Toy of the Year award. In 1986, Johnson was awarded the National Medal of Technology and Innovation by President Ronald Reagan.

Johnson died September 15, 1998 from melanoma at age 92, but his innovations will live on for generations.

Mr. Johnson may have been a small town schoolteacher with a college degree that had nothing to do with engineering or technology, but he had something more important that colleges can’t grant to any student: Uncommon Sense. And Thomas J. Watson had it too, overruling his own executives to bring not just Johnson’s test scoring machine into the company, but Johnson himself, leading not just to billions of dollars in revenues, but whole new industries and ways to do business.

You just can’t sell someone short because they don’t have an impressive job title or Ivy League college degree.

I’m Randy Cassingham, and I’ll talk at you later.

– – –

Bad link? Broken image? Other problem on this page? Use the Help button lower right, and thanks.

This page is an example of my style of “Thought-Provoking Entertainment”. This is True is an email newsletter that uses “weird news” as a vehicle to explore the human condition in an entertaining way. If that sounds good, click here to open a subscribe form.

To really support This is True, you’re invited to sign up for a subscription to the much-expanded “Premium” edition:

Q: Why would I want to pay more than the minimum rate?

A: To support the publication to help it thrive and stay online: this kind of support means less future need for price increases (and smaller increases when they do happen), which enables more people to upgrade. This option was requested by existing Premium subscribers.

Creative laziness is one of the top motivations for many of our best discoveries and innovations. 🙂

—

This …is True! -rc

Necessity is the Mother of Invention — along with the laziness! Good for Rey Johnson.

This is/was my very first exposure to a podcast. I listened to it attentively while simultaneously reading the corresponding transcript.

What a rewarding learning experience for a 78-year-old geezer…..and

I am indeed grateful you you for that!

—

I’m happy to have provided you with a new experience as well as some new knowledge, Michael. There are always interesting ways to learn something! -rc

This was the history I was a part of and love to hear it come out of your mouth. I so remember all the steps you covered and all the names you referred to….

Wow, was that IBM Santa Teresa Lab? My husband worked there for many years.

—

Not exactly. The first Silicon Valley lab was at 99 Notre Dame in San Jose, where RAMAC was developed; the San Jose City Council designated it a historic landmark in 2002. As noted, it was in an existing building that Johnson refurbished. They then had a new building constructed on Cottle Rd in 1957, which seems to be the location where RAMAC was produced. That (“Building 25”) was destroyed by fire in 2008; it had been vacant since the mid-90s. There were various other buildings on that site: it was 186 acres. It looks like IBM no longer has a presence there. Their main lab in the area is now IBM Almaden (still in San Jose), which is a rather large campus of buildings — on 700 acres — completed in 1985. That campus is located in the Santa Teresa foothills. -rc

I used to work at Cottle Road and remember that building and site very well. I was with IBM Global Services at the time. It was only a 20 minute or so walk from home to work back then. I’m sorry to learn that the building burned down.

I never heard of him. Amazing.

Efficiency is intelligent laziness.

One of the leaders of “motion study”, Frank Gilbreth (of “Cheaper by the Dozen” fame), always asked, when first arriving at a new consulting job, “Who’s the laziest guy here?”