In This Episode: When you really look into something that’s “obvious” and “common sense,” sometimes you’ll find that …the “experts” are wrong! This is the story of a man who was pretty sure the industry experts were wrong about something, and boy did it take him a lot of effort to turn that industry around. But he did, because his Uncommon Sense beat their common sense.

069: A Link to the Future

How to Subscribe and List of All Episodes

Show Notes

- Help Support Uncommon Sense — yes, $5 helps!

- Another tidbit: he accomplished all of this even though he apparently dropped out of high school in his junior year. Multiple universities gave him honorary doctorates, though!

- The photos mentioned are in the transcript. Click any of them to see larger.

- Link opened a second factory in Gananoque, Ont., Canada, during the war, since Britain required equipment be purchased from somewhere in its empire.

- The “first aquanaut” mentioned? That was Robert Sténuit …the Honorary Unsubscribe honoree in late 2024.

Transcript

Welcome to Uncommon Sense, I’m Randy Cassingham.

Edwin Link was born in 1904, and shortly afterward his father, Edwin Link Sr., bought out an automatic piano company in Binghamton, New York. (Most now call those player pianos). When larger theaters playing silent movies needed something with more sound to provide musical accompaniment to the films, he added player organs, too, and the quite successful business became known as the Link Piano and Organ Company.

That gave his young son exposure to mechanical things that performed some pretty complex tasks, thanks to his father letting young Edwin tinker with things in the shop. One thing he made was a sign that was mounted under the wing of an airplane that used perforated rolls — like his father’s player pianos used — to turn lights on and off to spell out advertising messages. He even connected a few organ pipes to make noise to attract the attention of people on the ground to see the message, also controlled by the perforated paper rolls.

When he was 12, the junior Link drew himself in an underwater vehicle, what today we’d call a submersible.

When he turned 16 in 1920, like a lot of young men at the time, Link wanted to become a pilot: not as idle entertainment, but it seemed to him like a good way to make money. He took a flying lesson, which cost him $50 (equivalent to about $650 today), but he was extremely frustrated that the instructor, Sydney Chaplin, the half-brother of movie star Charlie Chaplin, didn’t even let him touch the controls: he didn’t learn much. But he persisted, learned to fly, and by 1927 he was able to buy his first airplane. It turned out to be the manufacturer’s first airplane, too — the first one off their assembly line. That little company was called Cessna.

To help pay costs, Link would take just about any job he could find that would let him fly: he’d accept charter flights, and became a flight instructor himself, no doubt letting the students touch the controls. And that showed him why it was so expensive to learn to fly. Link, a lover of flying, with a background in how complicated mechanics worked, decided to come up with a way to teach new pilots to fly for a much lower cost.

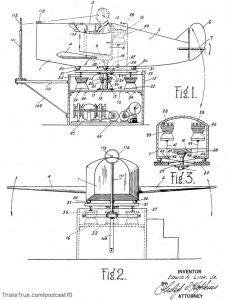

Have you guessed it yet? Link created the world’s first practical flight simulator, which took him a year and a half to build in the basement of his father’s factory, using bellows, valves, and motors from player organs to make the simulator move like a real airplane would. The cramped cockpit had all the controls and instruments a real airplane would — and as a pilot, he would know.

In 1929 he founded the Link Aeronautical Corporation to make and sell what he called the “Pilot Maker”; he was just 25 years old. The machine looked like a tiny airplane on a stand with all the mechanics needed for it to move in response to the pilot’s manipulations of the controls. The instructor sat outside and talked to the pilot over headphones, just like an air traffic controller might, and the simulator was connected to his desk, where a pen marked a map to show the course the pilot was on. That record could be studied afterward to identify which skills the pilot needed more training on. It was absolutely ingenious, especially for the time. There was no fuel to buy, and mistakes didn’t lead to crashes that killed the pilots and destroyed expensive airplanes. If the pilot did make a mistake, such as putting the simulator into a deadly flat spin, the simulator would spin around just like a real plane would.

Yet the so-called experts of the day scoffed. The way to learn how to fly is to get in an airplane and start flying! Isn’t that obvious? Isn’t that common sense? Even though Link figured flight schools would snap up his Pilot Makers, none of them bought any. The only business sector that was interested: amusement parks bought them as an awfully fancy fun ride. Still, Link used the machine to teach his brother George how to fly, so he was convinced it was an effective way to train pilots.

With flight schools not buying the Pilot Makers, Link opened his own school for aspiring pilots with an engaging proposition: instead of $50 for one flight lesson, he advertised that people could “Learn to fly for $85.” That was still a lot of money in 1929 — the equivalent of around $1,300 today — but it was a lot cheaper than the alternatives, and money really mattered: 1929 was the start of the First Great Depression. While pilot was a good job, the old way to train them was too expensive for a lot of would-be fliers during the depression, and Link successfully taught pilots using his Trainer. In 1931, he was awarded a patent for his design.

It wasn’t until 1934, after a series of crashes that killed airmail pilots (and destroyed expensive airplanes) that the U.S. Army Air Corps, which at the time transported airmail, decided to test out the Pilot Maker, and bought six. Six! Amusement parks had more than six! But, it was a start: the Air Corps figured the Pilot Maker would be a low-risk way to teach flying by instrument for night flying, which is when a lot of airmail planes needed to get to different cities. The trainers became known as the “blue box” since not only were they painted blue, but in operation it really was a box: the pilot couldn’t see out, and had to rely on the instruments in the cockpit. There are several photos on the Show Page so you can see what I mean. At the time, they cost $3,400; the equivalent today would be around $66,000.

Those six units led to orders from Japan, France, Britain, and the Soviet Union, but all in all sales continued to go pretty slowly until something happened to turn it all around. You may be guessing that, too: World War II broke out, and the orders for what was now known as the Link Trainer flowed in, and the company churned out 80 of them a week. During the war the U.S. Army bought 6,271 Link Trainers, and the Navy bought 1,045 more, which was enough to train more than 500,000 airmen around the world how to fly. Link also made specialized trainers for the military during the war, like the Gunnery Trainer taught airborne gunners how to shoot down enemy planes even though what they were sitting in was making evasive maneuvers to avoid being shot down by the gunners in the other planes! There were also Radar Trainers, Navigational Trainers, and Britain requested Celestial Navigation Trainers large enough to house the entire flight crew to train together, rather than just the pilot or navigator. There was even a special one for the Navy: the Aqua Trainer provided simulation of water takeoffs and landings, instead of solid runways.

After the war, Link kept updating the various Trainers and what they could teach, including one for jet bombers. Specialized Link Trainers were used by astronauts for their space missions, including moon landing simulators for the Apollo program, even though Link had sold the company in 1958. Interestingly, the company is still in business: the L3 Link Training and Simulation company is a division of L3Harris Technologies in Arlington, Texas. Today, flight simulators are a multi-billion-dollar business, for the same reason: it’s a lot cheaper to train pilots, especially about unusual emergency situations, on simulators, and there isn’t risk of a crash killing everyone on board.

So, what sort of other interests did Link pursue with his newfound freedom? Underwater archaeology! He developed equipment that enabled deeper, longer-lasting, and safer diving. He designed what he had envisioned when he was 12: submersibles, which differ from submarines. A submarine is fully self-contained, while a submersible has some link to another vessel, usually a ship on the surface.

The first “aquanaut” used Link’s equipment, the submersible decompression chamber, to stay underwater for more than 24 hours at a depth of 200 feet. Link built the submersible research vessel Deep Diver in 1967, which allowed researchers to go to depths and then exit the vehicle to free dive, and then return to the submersible: it’s called “lockout diving.” Nothing like it had ever been made before, but Link envisioned it and built it, creating a new class of vehicle for research. The original Deep Diver is now part of the Smithsonian Institution’s collection, and is displayed in Fort Pierce, Florida.

In an amusing circular idea, in the 1970s Link used parts from a non-functional Link Trainer flight simulator to build …an organ!

There are other innovations: Link was awarded dozens of patents. He put much of his resulting fortune into the Link Foundation, which still exists and has provided millions of dollars worth of grants and fellowships in aeronautics, simulation and training, ocean engineering, and various organizations that Link and his wife Marion supported.

“My approach to experimentation situations,” Link said, “is to nibble away at a problem until I understand it fully. I read, ask questions, and pester people. When I feel I’ve mastered it, I try to figure out its limits. I pass those limits only when I feel it is safe to do so.” Doesn’t that sound like a great example of Uncommon Sense in action? And look what he accomplished with that approach. When a tool didn’t exist to accomplish what he wanted to do, Link designed it, and then built it. “I never worked a day in my life,” he said: “I had fun, and I got paid for it.”

In 1976 Link was enshrined into The National Aviation Hall of Fame, which described him as “an unusual pioneer of aviation” — his contributions to the field weren’t really as a pilot, but on the ground, helping “make” pilots. In 1992, he was inducted into the International Air & Space Hall of Fame, and in 2003 the National Inventors Hall of Fame. He died in Binghamton in 1981, from cancer, at 77. At the time, he was working to design better wheelchairs.

There are a lot of stories about people who were told that something wouldn’t work, yet they pushed forward and put their futures on the line and pressed forward anyway. What seemed like “common sense” turned out to be totally, completely, wrong, and the innovators’ Uncommon Sense set a new baseline for what’s possible, and even what’s the norm in a profession that, well, the innovator ends up in some Hall of Fame or another. Edwin Link Jr. is one such innovator, and one of the reasons airliners are so safe today is because he invented the flight simulator, and modern simulators still carry his name more than 90 years later.

And wait until you see on the Show Page the current state of the art in flight simulators: it’s a long way past “the blue box.”

The Show Page for this episode is thisistrue.com/podcast69. There you’ll find multiple photos, a place to comment, and a link to help support Uncommon Sense without having to listen to stupid commercials. I was pitched today to join a group where podcasters like me would plug other podcasts in exchange for being plugged in some other show. In other words, commercials disguised as recommendations. I won’t play that game, but I do depend on your support so I can afford to not play that game. Even $5 really helps. Please click the Ko-Fi link on the Show Page to send a little support, and thanks!

I’m Randy Cassingham … and I’ll talk at you later.

Update

The “first aquanaut” mentioned above? That was Robert Sténuit …the Honorary Unsubscribe honoree in late 2024.

– – –

Bad link? Broken image? Other problem on this page? Let Me Know, and thanks.

This page is an example of Randy Cassingham’s style of “Thought-Provoking Entertainment”. His This is True is an email newsletter that uses “weird news” as a vehicle to explore the human condition in an entertaining way. If that sounds good, click here to open a subscribe form.

To really support This is True, you’re invited to sign up for a subscription to the much-expanded Premium edition.

Around 1990 I got to tour an American Airlines simulator facility with my mother’s church group. The only one in use on a Saturday was the air force version of the 707 with a couple of national guard pilots doing touch and go landings. There were several WW2 pilots in the group who got to try it out. It was amazing how much fun they had and how quickly they adjusted to a new plane. I crashed very quickly!

A friend of mine many many years ago was a Guard pilot and told me about this story. One of his friends was an airline pilot in his day job and he had always wanted a look at an airline simulator, so his friend snuck him and a navigator friend into the simulator room and got it all set up for them. My friend had fun with it and the navigator decided he wanted to give it a try, having never have been behind the controls of a plane before. Long story short, he crashed the simulator. Crashed it so hard that he broke the hydraulics on it. Sure glad that didn’t happen in a real plane. 🙂