In This Episode: Uncommon Sense can be found in very unusual places. In this story, a janitor at one of the plants at a multinational corporation had the cojones to call the CEO with an idea. And the CEO was smart enough to listen.

037: You Were Never Created to Fit In

Tweet

How to Subscribe and List of All Episodes

Show Notes

- Help Support Uncommon Sense — yes, $5 helps!

- An interesting tidbit in the “cola wars”: you likely know that Coca-Cola “won” the “war” by getting and maintaining a bigger market share than Pepsi. On the other hand, consumption of soda pop is way down. With its 1965 acquisition of Frito-Lay, PepsiCo is much stronger in the snack food category, and the real story is in the final numbers: in 2018, The Coca-Cola Company reported a net income of $6.43 billion on $31.85 billion in sales. But Pepsi: $12.51 billion net on $64.66 billion in sales.

- The Variety article I mentioned.

Transcript

Welcome to Uncommon Sense. I’m Randy Cassingham.

Richard Montañez grew up in Guasti, California, in the 1960s in a Mexican immigrant family. You may never have heard of Guasti: it’s an unincorporated town about 40 miles east of Los Angeles in San Bernardino County that used to be known as South Cucamonga, in an agricultural region where one of the biggest crops was grapes. In the 1960s, the “family business” (if you will) was to pick those grapes. Like many Mexican farm laborers, the Montañez family made very little money for their hard work: the entire family with 11 children lived in a one-room apartment at the labor camp. The bathroom down the hall was shared with a number of other families.

But Richard could go to school! Always a way to get ahead, right? He remembers his school bus was green, not the standard yellow like other school buses: just another way to separate the children, he says now. But there was another problem: in the 1960s, schools were starting to integrate, but that doesn’t mean they offered anything extra. They made a take-what’s-offered proposition, and they offered classes taught in English. Don’t know English? Too bad: you have to learn on your own — no help from the school. And certainly his parents couldn’t help: they only spoke Spanish.

But he started school, even though he couldn’t understand the teachers. At lunch, he thought the white children were staring at him: the other kids had sandwiches, and he had a burrito. When he got home, he asked his mother to make him a bologna sandwich for lunch the next day, because he “didn’t want to be different.” No, she said: “This is who you are.” The next day she made him two burritos so that he could give the second one away to help make a friend. And this is where the first glimmer of Uncommon Sense kicked in: that second burrito was so coveted that within a few days, he was taking lots of extra burritos to school …and selling them for 25 cents each! He was 7 years old.

“I learned at that moment that there was something special about being different,” Montañez said, “that there was a reason that we all just couldn’t fit into the same box.” Yet, one day the teacher asked the students to say what they wanted to be when they grew up. As the other children named things like teacher, astronaut, and doctor, “I realized I didn’t have a dream,” he says. “There was no dream where I came from.”

Frustrated with not fitting in, he eventually dropped out of school to join the rest of his family in the fields, picking grapes. He also worked at a chicken processing plant, and a car wash. That’s when a neighbor told Montañez that the Frito-Lay snack food plant in Rancho Cucamonga — the higher-class Cucamonga to the north — was hiring. At 18, he still couldn’t write well in English, so the neighbor helped him fill out the application, and he was hired on the spot. The pay: $4 per hour. In 1976, that was pretty good money: with inflation that’s about $18.25 an hour today, many times what he made picking grapes or washing cars. And the job came with insurance and other benefits: Frito-Lay had been bought out by Pepsi in 1965, so it was a big, big company.

When he told his family about his new job, his grandfather gave him some advice: “Make sure that floor shines,” he said, “and let them know that a Montañez mopped it.” Richard took that advice to heart, and decided he was going to be the “best janitor Frito-Lay had ever seen.” He worked hard at it: “Every time someone walked into a room, it would smell fresh,” he says, and “I realized there’s no such thing as ‘just a janitor’ when you believe you’re going to be the best.” His Uncommon Sense was really beginning to blossom.

He put in year after year on the job, but he didn’t stop at just mopping floors and cleaning toilets: he wasn’t just a janitor! When his shift was over, rather than go home and watch TV, he watched the machines to see how they worked — and they ran night and day. He asked the company salesmen if he could go with them to see how they worked. Some of the guys liked it when he came along since he spoke Spanish, and they took him to stores in Latino neighborhoods.

That’s when an idea began to form. “I saw our products on the shelves and they were all plain,” he said: “Lay’s, Fritos, Ruffles. And right next to these chips happened to be a shelf of Mexican spices.” He realized the company had “nothing spicy or hot” to appeal to Latino tastes. A few weeks later, Richard bought some elote, Mexican “street corn” coated with crema fresca, cheese, and spices including chili powder. And as he looked at what he purchased — a long yellow thing coated with spices, that in its way looked like a giant Cheeto — Montañez had what he called a “revelation”: what if I put spices like this on a Cheeto?

It was the early 1990s, and here’s where a little bit of luck came in: timing. First, the company’s CEO, Roger Enrico, sent a video to be viewed by all 300,000 employees worldwide. He told his employees, “We want every worker in this company to act like an owner. Make a difference. You belong to this company, so make it better.”

And second, a Cheetos machine broke down at the Rancho Cucamonga plant and a bunch of Cheetos were spilled in between cooking and the cheese powder being applied. “So I took some home,” Montañez said years later. He and his wife worked on coming up with a new chili-based seasoning powder. Once he was satisfied, “I let my coworkers try a few and they loved them,” he said.

He knew at the very least the southern California Latino population would like them, so he did what any enterprising janitor who was invited by the CEO to “act like an owner” would do: he pulled out the company phone directory, found the number he wanted, and “I called up President Roger Enrico, not knowing I wasn’t supposed to do that,” he said. “His assistant picked up the phone and asked my name and where I worked. I told her I was Richard Montañez, and I worked as a janitor in the Rancho Cucamonga plant.” There was no doubt a very long pause. But: “She was a visionary for even putting me through to Roger,” he continued. “He got on the line and said, ‘Hi Richard, I hear you’ve got an idea?’ He told me he would be down at the plant in two weeks and wanted to hear my idea.”

He wanted a presentation. The plant manager was livid. “Who do you think you are?” he demanded. “You’re doing the presentation!”

Well, Montañez didn’t know how to do such a presentation, so his wife got a marketing book from the library and they started work. As the big day approached, they made about 100 bags of the new flavor of Cheetos for everyone to try. “Here I was,” he said, “a janitor presenting to some of the most highly qualified executives in America. I was nervous but doing well, until an executive in the meeting threw me for a curve when he asked me, ‘What size market share do you think we should get with this product?’ It hit me that I had no idea what he was talking about, or what I was doing. I was shaking, and I damn near wanted to pass out. I thought hard and envisioned the sales racks that you see at the bodegas or the grocery store and realized what those shelves looked like, and I opened my arms to about as wide as the rack displays were and I said, ‘This much market share!’ I didn’t even know how ridiculous that looked. They could have laughed in my face right then and there, but the CEO stood up and put his arms out the same way and said, ‘Gentlemen, do you realize we have a chance to go out and get this much market share?’”

Six months later Frito-Lay launched a test in those East Los Angeles bodegas. Montañez went to those markets and bought bags of the new Cheetos they had. “I’d tell the owner, ‘Man, these are great!’ Next week, I’d come back and there’d be a whole rack.” He probably didn’t need to prime that pump, but Flamin’ Hot Cheetos were greenlit for national release in 1992. It was one of the most successful product launches in Frito-Lay history.

Six months later Frito-Lay launched a test in those East Los Angeles bodegas. Montañez went to those markets and bought bags of the new Cheetos they had. “I’d tell the owner, ‘Man, these are great!’ Next week, I’d come back and there’d be a whole rack.” He probably didn’t need to prime that pump, but Flamin’ Hot Cheetos were greenlit for national release in 1992. It was one of the most successful product launches in Frito-Lay history.

At the time, there were two varieties of Cheetos: crunchy and puffs. Since then, those have been joined by: Flamin’ Hot Crunchy, Flamin’ Hot Puffs, Flamin’ Hot Limon Crunchy, XXTRA Flamin’ Hot Crunchy, Flamin’ Hot Chipotle Ranch, Cheddar Jalapeño Crunchy, and more. The company also now produces Flamin’ Hot Nacho Doritos, Flamin’ Hot Chester’s popcorn, Flamin’ Hot Funyuns, and a Flamin’ Hot Taco at Taco Bell. And surely scores of other Flamin’ products. Montañez is no longer a janitor: he’s now the company’s North American Director of Multicultural Sales and Marketing.

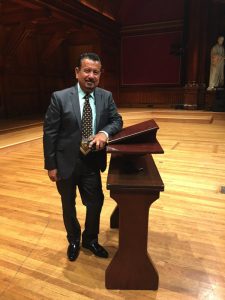

And get this: Variety, the Hollywood news magazine, reported last year that multiple studios competed for the rights to make a movie about Montañez. “Fox Searchlight nabbed the project in what was a highly competitive sale,” they reported. The title: Flamin’ Hot. Montañez is also a motivational speaker, and has lectured at Harvard and other schools. He still lives in Rancho Cucamonga, California, with his wife, not far from the Frito-Lay plant which is still operating.

To wrap this up, one last story to give you an idea as to how humble Montañez is, even with his enormous success. After he was promoted to the executive ranks of PepsiCo, he and the CEO took the company’s private jet back to its New York headquarters. He chose a seat and sat down, not knowing he had chosen the seat reserved for the CEO. Roger Enrico didn’t kick him out: Montañez would make the company billions! He simply chose another seat.

After they landed, Montañez found out about his mistake. “My heart dropped,” he said. Flying back to California on a commercial plane, he said he cried. “I said, ‘I’m so tired of embarrassing myself, so tired of not fitting in. Why can’t I be like everyone else?’ But,” he continued, “that little voice that’s bilingual, because it speaks to you in a language that you understand, said this to me: ‘Don’t you remember I told you when you were a little boy, you were never created to fit in? You were created to stand out.’”

If that’s not a full embracing of Uncommon Sense, I don’t know what is.

You can comment on this episode at thisistrue.com/podcast37.

I’m Randy Cassingham … and I’ll talk at you later.

– – –

Bad link? Broken image? Other problem on this page? Use the Help button lower right, and thanks.

This page is an example of my style of “Thought-Provoking Entertainment”. This is True is an email newsletter that uses “weird news” as a vehicle to explore the human condition in an entertaining way. If that sounds good, click here to open a subscribe form.

To really support This is True, you’re invited to sign up for a subscription to the much-expanded “Premium” edition:

Q: Why would I want to pay more than the minimum rate?

A: To support the publication to help it thrive and stay online: this kind of support means less future need for price increases (and smaller increases when they do happen), which enables more people to upgrade. This option was requested by existing Premium subscribers.

What an inspiring story. I encouraged my children and all the young folks I had the good fortune to teach over the years that you can do anything if you break the problems into small pieces then solve the little problems. The big ones then take care of themselves.

Great story. The janitor wasn’t afraid to speak up to the CEO and the CEO wasn’t afraid to listen to a janitor. Too often we don’t really listen because of who is speaking.

What an amazing and moving story. He was lucky that the guy at the top shared his vision, as it sounds like his immediate bosses just wanted a quiet life, but how many of us would have had Montañez’s staying power? Not me, that’s for sure.

Good for him! This story makes me very happy!

Makes me wish Cheetos were available in New Zealand.

—

I’m actually surprised they aren’t. -rc

Bob: find out what it would take to become their distributor!

—

My guess is, distribution is likely not the issue: manufacturing location is. Even if they’re made in Australia, shipping them in could add a lot to the cost. -rc

So make them in New Zealand. Duh!

—

Hard to say if the population is large enough. NZ is just under 5 million for the who country. The Los Angeles metropolitan area is more than 12 million, and a significant percentage is Hispanic (read: probably enjoys spicy food). It’s a risky undertaking to build such a factory if they’re not sure it will pay off. -rc