In This Episode: I had heard about the man I’m going to tell you about several times over the past several years, but I didn’t know the whole story of “The Man with the Golden Arm”. It’s a bit of a medical mystery and, as I researched all of this to understand what the heck it was that he did, I discovered he started displaying Uncommon Sense even as a child.

008: The Man with the Golden Arm

How to Subscribe and List of All Episodes

Show Notes

- To help support Uncommon Sense, see the Patron’s Page, or the form in the sidebar.

- My main sources: Wikipedia on the ABO blood groupings, HDN, and on Rh factors and how they were discovered by Drs. Landsteiner and Wiener. London Daily Mail. and Sydney Morning Herald.

- There are a couple of diagrams in the transcript below.

- Harrison died in his sleep in a nursing home on February 17, 2025, at 88, though that surprisingly didn’t reach the news until March 2.

Transcript

I had heard about the man I’m going to tell you about several times over the past several years, but I didn’t know much about him. Odds are very high that you’ve at least heard about him — in part because he was in the news earlier this year. But even if you read those news stories, I’ll bet you don’t know the whole story of James Harrison, who has been called “The Man with the Golden Arm”. It’s a bit of a medical mystery and, as I researched all of this to understand what the heck it was that he did, I discovered Harrison started displaying Uncommon Sense even as a child.

Welcome to Uncommon Sense, I’m Randy Cassingham.

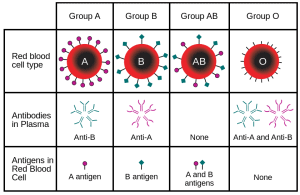

Do you know your blood type? There are four basic blood types, as discovered by Austrian physician, biologist, and immunologist Karl Landsteiner in 1900. The following is somewhat simplified, but you’ll get the idea.

Type A blood has type A antigens surrounding its red blood cells. Antigens stimulate production of, or are recognized by, antibodies. So if you give someone with Type A blood a transfusion from a donor who is Type B, which has type B antigens, or vice versa, the two kinds of blood will essentially attack each other with antibodies carried in the plasma: Type B has anti-A antibodies, and Type A has anti-B antibodies. As you might guess, mixing the two is very bad: it causes a significant adverse reaction and, considering the person apparently needed blood in the first place, they’re probably quite injured or ill, so the reaction could kill them.

As you’ve already guessed, the next blood type is B, which is essentially the opposite of Type A.

There’s also type AB. It has both A and B antigens, but doesn’t have any A or B antibodies in its plasma, so if a person with AB blood needs a transfusion, they can safely accept Type AB, Type A, Type B, or even the last type, Type O, because it doesn’t have type A or type B antigens either.

My blood type is O-positive. So what the heck is the “positive” part? That’s called the Rh factor, which was originally short for rhesus — a kind of monkey that has long been used for medical research. Once Dr. Landsteiner figured out the four basic blood types, there was still something that sometimes made, say, people with Type A blood react badly to a transfusion of even Type A blood. What was going on?

Enter another doctor and biologist, American Alexander Wiener. While still in medical school, Wiener did research on blood groups at Jewish Hospital of Brooklyn and also noticed the problem among blood types. Landsteiner and Wiener were quite confident about the A, B, AB, and O blood types, and in 1937, the two doctors figured out there were other antigens in the blood, the most important of which they called Rh type D. That’s what was causing the, for instance, A on A reactions that doctors could even see when mixing positive and negative blood in a test tube!

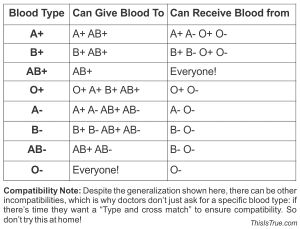

They dubbed it the Rh factor, after the monkeys they were using for the research: if someone had the extra Rh(D) antibodies, they were called Rh positive; if they didn’t, then they were Rh negative. Someone who has Rh positive blood can be given blood that’s either Rh positive or Rh negative, since they already had the Rh(D) antigens. But someone who doesn’t have the Rh(D) antigens — they are Rh negative — then you can’t give them Rh positive blood or they’ll have the reaction. And since 85 percent of people are Rh positive, it puts the Rh negative people at high risk. It took the two doctors a few years to get this all sorted out, but it’s the classification system still used today: it works quite well, and there are very simple blood tests to find out the person’s type, and their Rh factor. I have a chart on the Show Page to show how all this works.

Now, the Rh factor also explained another problem that had been going on for, well, forever, which was then dubbed rhesus isoimmunisation, or more simply Rh disease. When a woman is pregnant, some of the baby’s blood can enter her bloodstream. But what if the mother is Rh negative, and her baby is Rh positive? After all, 85 percent of humans are Rh positive, so Rh negative mothers are at significant risk. The mismatch causes a significant reaction, and since the mother has a much larger, much more established immune system, it easily overwhelms the baby’s blood, destroying its red blood cells, which is pretty obviously catastrophic: if the baby doesn’t miscarry and isn’t born dead, it can be born extremely ill, particularly suffering brain damage.

It’s called hemolytic disease of the newborn, or HDN, and it’s most common in Caucasian people. For them, about 10 percent of pregnancies involve an Rh negative mother and an Rh positive baby, and about 5 percent of those children died or were born extremely ill. And the reaction gets worse with each pregnancy, so that percentage of death or disability increased over time.

And that’s where we circle back to Australian James Harrison. When he was 14 years old — in 1950 after all this was figured out — Harrison had major surgery, and needed 13 liters of blood transfusions, or not quite three and a half U.S. gallons of blood! As Harrison was recovering in the hospital, which took three months, he was told about how the blood transfusions saved his life. Well, he decided right then and there that he would step up and donate blood himself! But hold on, they told him, he couldn’t donate until he was 18.

Yet here, we can already see Harrison’s Uncommon Sense: even at just 14 years old, he grasped that people volunteering to take time out of their day every couple of months and donate blood helped keep people like him from dying, and he vowed to return the favor — or, really, pay it forward.

Sure enough, when he turned 18 in 1954, Harrison started donating blood. I never found out his blood type, but whatever it is, he’s Rh negative, and that turned out to be important. Because when his donated blood was tested, the blood bank noticed that there was something special about Harrison’s blood, or really his plasma: it had strong antibodies against the Rh(D) antigen.

So what? So this: the doctors in Australia realized they could isolate those antibodies and create a vaccine for Rh negative mothers carrying Rh positive babies! And even better, it didn’t take very much of Harrison’s plasma to make a dose of the vaccine: in fact, with one donation they could make hundreds of doses, and each one prevented the nasty HDN, the hemolytic disease of the newborn and the resulting deaths and disabilities. And even better than that, they discovered when Harrison donated blood, his body responded in part by making even more of the antibodies. It took awhile to figure this all out so they could start making the vaccine, and make it available, but in 1967 the first mother with Rh negative blood, carrying an Rh positive baby, got the first dose of the vaccine at Australia’s Royal Prince Alfred Hospital, and the baby was born without disability — totally healthy. The HDN was prevented.

But, what made Harrison so special? Doctors think he probably got a small amount of Rh positive blood when he had his transfusions as a teen, and rather than getting sick from it, his immune system developed the antibodies to fight off the Rh positive invaders, leaving him with a kind of super-blood.

As the implications of this settled in on Harrison, it went through the special filter I call Uncommon Sense. Rather than donate whole blood, he could do apheresis instead. What’s that? The blood is taken out, and the portion that’s needed is extracted, and the rest is put back into the donor. For plasma, it’s called plasmapheresis: a special machine takes the blood, separates out the plasma and holds on to it, and puts the rest back into the donor — like the red blood cells. And here’s the thing: whole blood donors can only donate every eight weeks. A plasma donor can donate much more often. Harrison, realizing that every donation could save the lives of hundreds of babies, typically donated weekly! Even though there’s another thing about apheresis: instead of taking 10 or 20 minutes to donate a unit of whole blood, apheresis takes about an hour and a half. But to save so many babies, he was willing to do it.

But wait, there’s more: by studying Harrison’s blood, researchers realized that he wasn’t one of a kind: over time, they figured out how to identify others that had the anti-D antibodies, and save more and more babies all over the world. In Australia today, there are 160 donors with the antibodies. That’s good news, but only 160! The resulting Anti-D vaccine, based on research on Harrison’s blood, is now on the World Health Organization’s List of Essential Medicines, and someone out there, or really many someones, are taking the time to donate their special plasma so it can be made.

Meanwhile, even after Harrison’s wife of 56 years died, the next week he kept his appointment to make another donation. “It was sad but life marches on and we have to continue doing what we do,” he said. “She’s up there looking down, so I carry on.”

But, Harrison couldn’t carry on forever: just as he was not allowed to donate blood until he was 18, earlier this year he turned 81, and the rules in Australia dictate that people can only donate through age 80. So just before his birthday, on May 11, 2018 he gave his last donation — his 1,173rd donation. And that’s why he was in the news earlier this year, even though few reporters really understood what made him special, which is why I couldn’t grasp it.

And I did the math: over his 63 years of eligibility, Harrison donated blood or plasma on average about every 2.8 weeks. That’s so much blood and plasma that it’s estimated the vaccines made from his blood alone saved about 2.4 million babies from HDN. Man, did he really pay it forward! Can you see why they called him “The Man with the Golden Arm”?

As he gave his last donation, he was surrounded by mothers holding their babies that had been saved thanks to the antibodies in his blood.

Way back in 1999, Harrison was awarded the Medal of the Order of Australia. That’s nice, but really: what’s a medal compared to the knowledge that you saved 2.4 million babies from a horrible fate? Especially when, after working with him for 23 years, one of the employees at the Australian Red Cross Blood Bank in Sydney finally told Harrison she was one of the mothers whose child was saved thanks to his donations. But that probably wasn’t as sweet as when his daughter needed the vaccine, and was able to give birth to Harrison’s healthy grandchild. So maybe you can see why, as he aged, Harrison said, “I’ve never thought about stopping. Never.”

The lesson here isn’t that everyone should go out and donate blood or plasma. Rather, it’s that when a bunch of anonymous volunteers helped save Harrison’s life, he wanted to repay the favor, to pay it forward, even though it cost him a lot of time, and surely plenty of scar tissue inside his elbows! He realized that the donors who helped him obligated him to do something in return. And when it became clear how important his specific blood was, he made it his life’s mission to save as many babies as he could, and what his blood started will continue on long after he’s dead, because he took the time to let researchers study him.

Those with Uncommon Sense pay it forward. Obliviots? We’ve all dealt with them: they’re obstructionists, making everyone else’s lives harder. Yet I’ll bet it’s easier for you to name 25 obstructionists than ten people with Uncommon Sense.

So: who do you owe for your place in this world? Have you paid it forward? That’s something to think about. I sure have, and I’ve worked hard for many years to pass the favors on.

The Show Notes for this episode, including links to my sources, are at thisistrue.com/podcast8

I’m Randy Cassingham … and I’ll talk at you later.

– – –

Bad link? Broken image? Other problem on this page? Use the Help button lower right, and thanks.

This page is an example of my style of “Thought-Provoking Entertainment”. This is True is an email newsletter that uses “weird news” as a vehicle to explore the human condition in an entertaining way. If that sounds good, click here to open a subscribe form.

To really support This is True, you’re invited to sign up for a subscription to the much-expanded “Premium” edition:

Q: Why would I want to pay more than the minimum rate?

A: To support the publication to help it thrive and stay online: this kind of support means less future need for price increases (and smaller increases when they do happen), which enables more people to upgrade. This option was requested by existing Premium subscribers.

What an inspiring man! I wonder if he’d enjoy an Honorary Subscribe to This is True and Podcast 8?

—

Not sure what you mean. Even if I had his email address, it’s not proper to subscribe someone to an email publication they’ve never heard of. Hopefully, if he’s interested in tributes like this, he’ll find it on his own, or have it pointed out by a friend. -rc

I was able to listen to this podcast (while I usually just read the transcripts) and found the intro and exit music distracting. Is that on each one? Can you make the volume quieter maybe? It’s kinda neat (to me) to be able to hear you and how you place emphasis on passages — after having read you for so many years. *Side note, donating or “selling” my plasma put food on the table when I was a young single mother 20 plus years ago.

—

I’m glad you enjoyed it. Yes, the music is on each one, and is already turned down by 8 db to keep it significantly lower than my voice. -rc

Great information. I am O- and have always been curious about how all that worked and you just solved the nagging questions I had. I am a little confused though. You state that the first mother given this vaccine happened in 1967. Was this information specific to Australia? The reason I ask is that I was pregnant in 1966 and my baby was A-. I was given the vaccine in June of 1966 in the U.S. Thus the confusion.

—

Specific to Australia. Researching what other countries did was beyond the scope of telling his story. But if you find out, I’ll be interested to know! -rc

Thank you for this wonderful, educational story! Excellent explanation of blood types and Rh factor backed up with charts and graphics that are easy to understand.

Many years ago, when I was in my teens, I would regularly donate plasma because technicians at the “Plasma Center” (in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania) told me there was something special about my blood that they needed to make the RH vaccines. Although I didn’t understand how it all worked or why they seemed to value my plasma so much, they said it was a good thing so I’d go there once or twice a week to donate. This was back in 1977-78 and I continued donating plasma until moving away to begin my military career a few years later.

I honestly haven’t thought about it for years. However, your explanation with this story has inspired me to contact my local blood bank or hospital to see whether I’m still a good candidate to donate plasma for the anti-RH vaccine. I’m a lot older now, but hopefully still have plenty of time ahead before reaching the 80-year age limit. 🙂

Perhaps my yellow “blood juice” can still be used for the vaccine to save a few babies these days. Will keep you posted on what I find out. In the meantime, I’d appreciate any additional information or resources others can share for plasma donation, particularly for any donation centers here in Virginia.

Thanks again for the great, thought-provoking podcast!

—

How cool! I would think calling “all” the blood banks in your area would get you to the one that would know about this. If they don’t know what you mean, then ask to speak to someone else, like their medical director, who presumably would know more about it. Yes, please keep me posted. -rc

Found this with a quick Google search …and they just happen to have a donation center about 30 miles from my home. 🙂

Definitely going to contact them about donating plasma.

—

30 miles is a commitment, but great! Let me know how it goes. -rc

I am a woman with O- blood. My first son was born in 1967 and the vaccine wasn’t available then but I got it for my second son born in 1969. This was in California. Over the years I donated blood many times as a universal donor. Had to give up as my body wouldn’t give it up and rarely could give a pint. Bruised elbows resulted. But I happily donated while I could. Easiest way to be a hero!

—

Awesome. 🙂 -rc

A great explanation of blood groups, which despite a scientific education I’d never understood before. And it’s amazing that one person can directly save or improve the lives of such an enormous number of people. No medal is big enough to reward that!

My old army dog tag is on a teddy bear on the shelf behind me, and it says (as the UK tags do) that I’m O+, so my years of donated blood were very flexible, but not even a drop in the ocean compared to this guy!

—

It all counts toward the goal to save lives, so don’t sell yourself short. -rc

I just came across this podcast due to you mentioning Harrison in This Is True today. RIP.

I was an RH baby back in the 1950s, before this vaccine became available. My mother was O-, and I am O+. My next older sibling died shortly after birth due to the same situation. Several years later, doctors had worked out a new treatment, and my parents tried again. The doctors induced labor two weeks early, then gave me two exchange transfusions of O- blood, so that my mother’s antibodies, still in my bloodstream, would have less to attack. “Exchange” means that they added O- in one stream, and removed some of my own O+ in the other. Weird, but it worked! My younger sister needed many more exchange transfusions — 9 or 10 of them. She survived, too. I am not sure anyone ever had more, as they learned how to do this in utero after that.

The vaccine is a much preferable treatment.

—

Indeed. Thanks for your first-hand information. -rc