I’ve heard from several friends who spotted me in the Wall Street Journal today. It was just a tiny mention in an article about the Dvorak keyboard, an ergonomic alternative to the common “Qwerty” layout that you probably use.

Anti-Ergonomic

Qwerty was designed in the 1800s by the inventor of the first commercially successful typewriter, and there’s a reason it’s a bit convoluted: Christopher Latham Sholes’ invention had a big problem with key jamming. The type bars didn’t have springs on them (like typewriters had in the 1900s), and fell back with gravity. So the mechanism was sluggish, and it was easy to get fast enough on the machine — even when typing with two fingers, as Sholes expected everyone to do — that the bars would often jam.

His solution: move the most-used letters away from each other so they were less likely to jam. So yes, the keyboard you use today is that way to accommodate the lousy mechanics of a late-1800s invention. “Adapt the humans to the machine” is pretty much the definition of anti-ergonomic, but that’s the way things were done then.

A Better Way

In the 1920s, a team at the University of Washington, led by Dr. August Dvorak, was inspired to make things better after hearing about how inefficient Qwerty was from Drs. Frank and Lillian Gilbreth, the pioneers of time and motion studies — efficiency! (You know them from the book/play/movie Cheaper by the Dozen.)

Dvorak’s team spent 12 years (oh for a decent computer to crunch the data!) to come up with their “Simplified Keyboard” design, now referred to as the Dvorak keyboard. I literally wrote the book on the layout in 1986 — my first book. (Like most of my early work, it’s in dire need of revision, but I’ve been kinda busy lately!) It’s now out of print.

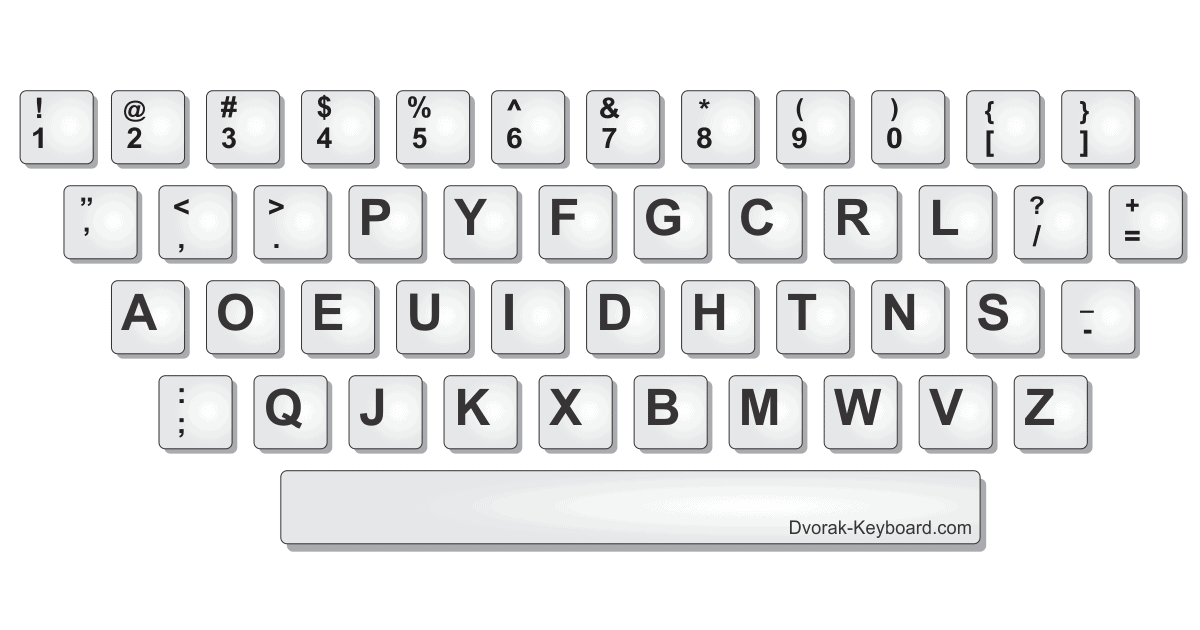

Ergonomic Design

The Dvorak team took a lot of things into consideration: typing “should” be done from the home row, where your fingers normally rest (though only 32 percent is done there on Qwerty). By putting the vowels on the left home, and the most-used consonants on the right home, Dvorak allows 70 percent of typing to be done on the home row.

It’s easier to reach up than down, so the next-most-used keys are a rank up. The lowest rank is reserved for the least-used keys, like Q and X.

By having the vowels and consonants laid out like that, there tends to be a back-and-forth motion with Dvorak. While one hand is typing the first letter you need, the next letter is most likely to be typed by the other hand, so it can get ready to strike it: that’s one big reason Dvorak is notably faster.

It Gets Deeper

Then, they studied letter pairs and triplets. For instance, words with “T-H” are common in English, so that pair (and dozens of others) were accommodated to make them easy to type.

How? Drum your fingers on the table: it’s easier to go from your pinky in than from your pointing finger out, right? That “inboard stroke flow” is designed right in to Dvorak. The T-H? Right hand: the T is under your middle finger, the H under your pointing finger — outside in. Easier to do that than the other way around.

So in addition to being designed to accommodate English (and it does a decent job for other languages based on the Roman alphabet), it’s also designed to accommodate your hand: in short, it’s ergonomic.

Yet schools still teach kids Qwerty, even though it’s (as you can probably see!) significantly easier to learn and type on Dvorak (you may remember the horror of learning how to type!) Yep: we’re still causing kids pain because of the mechanics of an 1890s machine when something better has been available for generations.

My Generation Too

Despite being born a couple of generations later, Qwerty was thrust on me, too: there was no choice.

I learned to type in high school (teacher Benjamin Stein probably still has nightmares about me: rather than practice random garbage, I used my class time to write him letters, like the one from the typewriter dealer saying the school had missed a payment, and a man would be there in the morning to repossess the machines. Yeah, I was a wise-ass right from the start.)

I switched to Dvorak in college; I wanted to be a writer, after all, and I knew that I’d be typing a lot. I had hit a plateau of 55 wpm on Qwerty, which is pretty darn fast for average people, but wanted to go faster. I now type well over 100 wpm, thanks to Dvorak.

And despite all the writing I do, working 8-12 hour days, 7 days a week, I’ve never developed carpal tunnel syndrome (or even tendinitis) from all the keyboarding involved during such workdays.

Enough Introduction

Anyway, the WSJ had an article about the layout today, with an amusing angle: sure, Dvorak is built right in to Windows and the Macintosh operating systems, but what about the poor schlubs who have to text and email from their smartphones? They’re all Qwerty! The reporter interviewed me for a good 45 minutes, but only used one brief quote from me, which is fine: I didn’t really support his thesis.

Yes, I think “soft” keyboards like the one the iPhone projects should be configurable to Dvorak. But unlike a “real” keyboard, phone keyboards can’t be used for touch typing: you have to look at them and use one or two fingers. There’s no advantage to ergonomics in such a situation, so whatever the user is used to is best. And as far as looking at a keyboard, I actually prefer Qwerty on my phone, since I don’t look at my Dvorak keyboard when I type, since touch-typing is so easy — I don’t need to!

While my Dvorak book is no longer available, Dr. Dvorak’s scientific study of keyboarding from 1936, Typewriting Behavior, which I used extensively in my research for my book, is! I ended up with the Dvorak family’s entire stock of his book after his widow died; I had the honor of meeting Hermione Dvorak just before my book was published, and corresponded with her for several years. So her husband’s book is available via my shopping cart.

How About…?

The number-one question from people who saw the WSJ article: can someone touch type on both? Yes, if you use both regularly. It’s not a big deal: many “touch type” on a touch tone phone and on calculator or “num-key” pads, even though they’re very different: the phone has 1-2-3 along the top, the calculator/keypad has 7-8-9 along the top.

You may never have even consciously noticed, but you can do both, right?! But I haven’t kept up with Qwerty, and have lost the ability to touch type on it: I have to look at the keyboard and type with two fingers. If I look away, I revert to my over-100-wpm Dvorak typing.

(Want proof Dvorak is fast? I whipped this page out in about 45 minutes. 🙂 )

Also see my mini-site on the Dvorak keyboard.

There is an alternate piano keyboard design, where the black and white keys are all the same size and shape. This makes transposing keys (musical keys) a simple matter of moving up or down a few keys (piano keys) instead of having to use completely different fingering when you change (musical) keys. It’s a great idea that died rather quickly. People who already knew how to play (and play in different keys) saw no reason to start from scratch. And if they did learn the new keyboard they’d be in trouble when they sat down at a standard keyboard later.

Likewise, it doesn’t matter if the Dvorak keyboard is more efficient. It’s not going to be a big enough improvement for most people to invest the time learning it (and unlearning QWERTY), only to find it’s a hindrance when they sit down at someone else’s keyboard. Most people aren’t going to see their speed doubled — they’ll maybe get 10% faster — and that’s not enough to deal with the downsides.

—

I hate it when people don’t truly read my stuff before they comment: you’ll note I didn’t urge anyone to switch layouts, even though they certainly don’t have to “unlearn” Qwerty: most of what you have to learn when you learn how to type is how to move your fingers around the keyboard — the physical “muscle memory” of typing. That’s used no matter what keyboard layout you have. And, as I said, people can certainly type on both if they wish, so there’s no issue with “someone else’s” keyboard even if it wasn’t absurdly simple to remap it. Then you figured you’d guess at what speed increase people might get — “maybe 10%” is a far cry from my own 100 percent speed increase, which is not unusual. But despite all that, I still didn’t urge people to switch. I did lament that we still foist Qwerty on kids when there’s something much better available, and much easier to learn. And that is a sad state of affairs. We can remap computer keyboards with the click of a mouse. There simply isn’t an issue of “we have to” continue down that idiotic educational road because Qwerty is “standard” when Dvorak is built into virtually every computer. -rc

I’ve gotten completely out of the Dvorak habit after playing with it in the early ’90s. It’s just been getting harder on keyboards without removable keys! Maybe I need stickers. 🙂

Not only is the Dvorak keyboard easier and faster for most humans, it’s especially faster for one-handed typists. Some of my experimenting in the early ’90s included creating Dvorak keyboard layout files for the Macs of the era, including right-handed and left-handed one-hand variants. I see Snow Leopard includes those as well as the basic layout! I’ll have to play with it some more.

—

The one-handed Dvorak layouts (created by Dr. Dvorak from his existing data for a man who lost his arm in World War II) are also included in Windows. -rc

I’ve heard of this keyboard before, and I find the idea fascinating. I type relatively fast on Qwerty, 55 to 60 wpm – how quickly can one learn this new setup when already very good at typing on what’s basically an archaic keyboard? In theory, would I have to retrain my neural connections, or can one be cross-trained? 🙂 I’d hope for the cross-training option, if this new keyboard were to be installed in some settings and the Qwerty setups in others…

—

You posted this before I answered Dave (first comment): the same “muscle memory” is still used, so it’s doubly easy if you do decide to switch. Remember when you first learned to type, you had to type nonsense words? “FJKS” and such? That’s because as you’re learning the home row, there’s not too many real words you can type there. But because of Dvorak’s language-based design, thousands of words can be typed using only the home row. The catch: you have to use lessons that are designed by someone who really understands the Dvorak layout so that it uses real home-row words from the start. The best tutorials I know of are offered by Keytime in Seattle. I believe that with reasonable practice using their materials you’d be able to reach your current speed in about 5-6 weeks — and then keep going up from there. And remember, Dvorak isn’t only about speed, it’s about comfort, too. It’s a lot easier on your hands. But the speed is still nice! -rc

I became curious about the Dvorak keyboard because Piers Anthony mentions it in some of his writings, and he’s a favorite of mine. Ultimately, I’m too lazy to actually try it out.

About the layout though, I don’t know there is a difference in drumming fingers in or out. Of course, that’s one of the things I do often. Anyway, I liked the brief history of the qwerty. I remember in school asking why the letters were they way they are and was told because that’s the easiest. Well, of course it’s easier for those that already know it.

—

Just so! Yes, Piers is one of several writers I know who use Dvorak. “Inboard” finger drumming is definitely easier for most people. I suppose some who use their hands a lot in their work (e.g., sleight-of-hand magicians, some musicians) wouldn’t really notice a difference. -rc

You got me curious about the Dvorak keyboard, but I have a question, I’m from Mexico and I write in spanish, in this case this layout wouldn’t be as efficient for me? And for having the same efficiency there should be a keyboard with spanish words in mind?

—

Typing on Dvorak en Espanol would be more efficient than in Qwerty, since many of the benefits would apply — the two- and three-letter combinations are very similar, for instance. The addition of accents is probably the biggest issue, but that’s already an issue with Qwerty…. -rc

I’ve often wondered about Dvorak, as the claims made are so good, and then I ran across the “Fable of the Keys”. Before just quoting that, I did some more searching and found the debunking of that article (mostly by you). What didn’t seem to come out of either side is any scientific studies after Dvorak’s initial one and the Navy one on their typists.

Is there more data to back up the claims? Most of what I read seems to be anecdotes.

—

I’ve been calling for a good study for many years, but the patent on the Dvorak layout expired decades ago, so there is no financial incentive to do rigorous studies in the private sector. Someone once left money in their will to a university to do a study, but the university spent the money on something else instead. The only study I know of has been by Keytime, but as far as I know they haven’t actually published their data, and I don’t know how rigorous their methods have been. -rc

I switched to Dvorak years ago, with dreams of vastly improved typing speed. What I’ve actually found is that my typing speed is about the same as with qwerty (somewhere around 50-60WPM). This really puzzled me, but after I started thinking about it (while typing) I realized that for me, my head is the roadblock. I can certainly think of things faster than 50WPM, but I just can’t get the fingers to move any faster. I suspect this is because I do computer work all day; most programming languages are far, far less wordy than English, so I’m used to putting a significant amount of thought into everything that I type.

That said, I’m completely convinced that Dvorak has saved me from RSI. That alone makes the switch completely worthwhile.

I spent some time playing with Dvorak’s layout, but it ended up just not being worth it to me. About half my work day is spent using other people’s computers (I’m a support tech at a university), so I’d have to get everyone in the department to change to see a big change.

That said, my peak typing speed with Qwerty was over 100 wpm, and I currently run about 70-90, depending on what I’m doing and how much typing I’ve done recently. If I were see the same kind of improvement with Dvorak that a lot of people seem to, I’m not sure my brain would keep up with my fingers… the advantages in comfort, though, are what keep me considering it.

I read your Dvorak page a long time ago, but reading this again made me realise something that would be a really strong incentive for me to learn to use this layout:

Japanese would be extremely suited to the Dvorak layout; since in the japanese “KANA” alphabet, 45 of the 46 characters use a vowel (aiueo), or a vowel and a consonant (one of kszjtdnhbpmyrw), so that alone would lead to a speed increase. The left hand would hardly have to move!

Although I do not see it catching on here any time soon: Even though keyboards here have since the DOS era featured both QWERTY and the Japanese KANA characters assigned one to a key, almost everybody I know still uses the QWERTY layout to input the KANA, with two strokes per KANA even though the KANA layout would reduce keystrokes by 50% (A single “TA” instead of “T” and “A”).

As an aside, it’s probably just me (is it?) but, “Drum your fingers on the table: it’s easier to go from your pinky in than from your pointing finger out, right?”

I seriously cannot do this! My ring finger simply will not comply. Index to Pinkie is about five times faster and much more natural. The result of too much two finger typing perhaps? Despite twenty years as a software engineer I have never had any formal typing training. But I do think my fingers’ “muscle memory” have learned the patterns involved in typing those Japanese KANA.

I now make more mistakes when typing English than when typing Japanese. (And most of the mistakes in Japanese are from typing too fast, so that left and right hand keystrokes get out of order.)

Thanks again for a thought-provoking post.

—

See if you can find the work of Hisao Yamada of the University of Tokyo, who did a lot of work on efficient keyboarding for Kana. He was quite fascinated with Dvorak’s methodologies, and wrote several papers on the subject. He’s probably long retired by now — I used to correspond with him years ago. -rc

I don’t remember where I first encountered this idea, but I’ve seen quite a bit of evidence that it’s true: In most situations where standards exist, the rules that are used are the first ones that are “good enough” according to widespread acceptance.

The best example of this is, of course, Qwerty vs. Dvorak. Qwerty was “good enough” that people could be productive with it. Dvorak probably is superior, but the chicken-and-egg dilemma is at least part of the problem: almost everyone knows how to use Qwerty, therefore that’s the default (and sometimes the only) choice to use, therefore that’s what’s taught, therefore that’s the default, and so on.

Another example is the situation we have with major airports throughout the United States. The first jets had their entry doors 15 feet above the ground, and at first someone had to roll a giant stepladder up to the plane to allow passengers to get on and off. It didn’t take long before the biggest airports started building terminals that load and unload passengers from the second- or third-story. Today, it would be easy to build a jumbo jet with the door much closer to the ground, and in emergency situations where the plane has to be emptied quickly, this would be MUCH safer. But if any airline owned a jet like that, it would be inconvenient to use at major airports — so the high-door “standard” remains.

Anybody remember when the United States switched to Metric? I was in school at the time, and I had to sit through class after class, learning how many millimeters are in a meter, how many milligrams are in a gram, how many milliliters are in a liter, and so on. (The very fact that all three questions have the same answer, is what makes metric superior.) That was what, 30 years ago? Today you can buy a 2-liter bottle of soda, and my car’s speedometer has both Metric and English markings, but I don’t think anything else in my life has changed at all… it seems that inches/feet/miles, ounces/pounds, ounces/cups/gallons are all “good enough”.

Beta versus VHS is an exception, but there’s a good reason for that. Beta did come out slightly before VHS, and it was (very slightly) superior. If you had Beta equipment and VHS equipment of similar quality, and you recorded a program on both and then played them both back, they would look identical to most people. But if you played them both back 50 times, the VHS recording would start showing wear before the Beta format did. So Beta was superior, but Sony charged royalties — making it more expensive. So it wasn’t “good enough” after all, and VHS won the format war.

Do you have a particular brand or brands of Dvorak keyboard you recommend? Again, after considering it some years ago, I’m thinking of switching, if only to avoid injury.

—

You’ll rarely find hardware keyboards with Dvorak, since “the” way to switch is to use your existing keyboard, and just set up Windows (or your Mac OS) to map it to Dvorak. That’s free. If you want the keytops to reflect the layout, the usual option is to use clear labels which allow the Qwerty legends to show through, but add the Dvorak marks so if you do a hunt and peck operation (or want to, say, find Ctrl-Z to “undo”), you won’t be confused if you look at the keyboard. Keytime is one of several sites that sell such “overlays”. -rc

Very thought provoking, but I would rather swithc to a Maltron (or equivalent) keyboard for ergonomic reasons, rather than the (IMO) half-step of Dvorak.

—

Both are half steps in my opinion: the shape of the physical keyboard has nothing to do with the layout of the keys. It’s important to make BOTH be ergonomic. I don’t like the Maltron myself, but I use one that’s just as bizarre-looking: the contoured Kinesis — with Dvorak, of course. -rc

I switched several years ago, and while I don’t know what my actual speed is, I certainly am faster than I was before I switched. I agree that it is not enough to be ideal, but it most definitely is better than teaching qwerty.

Riley (and others interested in other keyboards that are hardwired) For the past few months I have used the Typematrix keyboard, labeled Dvorak, of course. I do find that the typing blocks are a little close together for ideal use, but it makes it possible to slide the keyboard in a laptop bag to cart it around. Can’t have everything, I suppose.

Correct me if I’m wrong, but can’t you just pop off the keys and change the arrangement? The keys on an Apple keyboard can be swapped around…try it.

—

It depends on the keyboard. My laptop, no, since there’s a little joystick in the middle so the keys around it are cut to fit. Many desktop keyboards have different-shaped keys for different rows, so they don’t rearrange either. But some can be rearranged physically once the mapping is in place. -rc

I had heard about the limitations of QWERTY before, but like most had just learned it in high school and haven’t got around to trying it out yet. I’m quite inspired to hear that you can get 100+wpm with it!

I found it amusing when I was given a Blackberry at work that the tiny little keyboard was in QWERTY with two letters to each key. I tried to imagine anyone putting their fingers on the home keys and typing away, impossible!

So I have learned to ‘thumb-type’ on the 1/2 qwerty keyboard, yet another awesome skill for my brain to remember along with touch type QWERTY and 1=ABC, 2=DEF phone keypads. Muscle memory is amazing!

I too have been a user and supporter of the Dvorak key layout for many years. And I too was first introduced to it by Piers Anthony. I as well used to ‘pop out’ the keys on the keyboard to match the layout at first, but…

I wouldn’t worry about this so much. After all, the point of learning to touch type is too NOT look at the keys! So it doesn’t really matter what label, if any, is on the keys anyway. At least on Windows, you can set it up to switch between Qwerty and Dvorak with a click of the mouse or a key combination such as Alt-Shift. So you can set this up on any computer easily. Even one you are only using temporarily. Of course… this is really funny if you accidentally leave the Dvorak layout on a friends computer…. 😀

Another reason for the use of this layout is for those suffering hand damage. Yes, I know that Dvorak invented single hand layouts, but In my case I am sadly missing the index finger of my left hand. So using the Dvorak layout greatly improves my typing ability. I type with my left hand one key to the right of normal (ie. middle finger on the ‘u’ (‘f’ on the qwerty) and my dexterous left pinky does double duty on the leftmost two positions. I taught myself to re-learn to this layout and it wasn’t that hard at all, and I’ve never regretted it. I encourage anyone to try the Dvorak layout. And as a professional musician (yes, a three fingered six-string bassist…) I can attest to the fact that it is great for avoiding RSI or carpel tunnel problems…

Thanks to Randy for all your work on promoting this ideal, and of course for all your myriad publications… long, long time fan here!

—

I think it’s cool you don’t let your missing finger get in your way — on the computer or on the bass. And if Dvorak helps you with it, I love it! -rc

Just had to brag a bit. 😉 I’m a pianist, and I think that’s why touch typing is fairly easy for me. I recently clocked myself at 105 words per minute on a full-size QWERTY keyboard, and 45 words per minute on my Nokia N810’s thumb keyboard. I’ve taken detailed class notes with my thumbs several times.

When I write, the bottleneck is my brain, rather than my fingers. I usually type faster than I can think up words to put down.

I’m intrigued by your Dvorak article though. It makes me want to learn Dvorak, just to see how fast I could become.

—

105 wpm is fast on Qwerty; I remember typing competitions being won at 125 wpm (the fastest Dvorak typist was clocked at 212 wpm, but she was typically excluded from competitions). My mother was also a pianist and sometimes-secretary; extra-strong fingers did help her: she could blaze even on a manual typewriter. If you do switch to Dvorak, let me know how fast you get! -rc

“inboard stroke flow”

I’m sure this doesn’t invalidate Dvorak’s work, but I don’t find this to be the case for me at all. Perhaps it’s because I’m left-handed or mouse-a-dextrous or maybe just a habit that I acquired in childhood, but I find it difficult and awkward to drum them inward and natural and comfortable to drum outward.

I guess I had better stick with QWERTY. 🙂

—

Luckily, that’s only one aspect of the design, meant to show the tiny details they considered. -rc

I was intrigued by your statement that you have never had carpal tunnel problems using Dvorak. As one who has had surgery on both hands for this problem, I believe that if Dvorak will slow the epidemic we should shift into panic mode and change over immediately! Maybe Obama/Pelosi will grant health insurance premium breaks to those who use Dvorak (similar to non-smokers).

—

I’m certainly not going to guarantee that someone who uses Dvorak will never get RSI, but I do believe it would reduce the incidence, perhaps markedly. -rc

I read an interesting paper many months ago which calls into question the superiority of Dvorak. It includes an overview of the first typing machines’ key layouts and the initial development of touch typing. One of its conclusions is:

“The claims for the superiority of the Dvorak keyboard are suspect. The most dramatic claims are traceable to Dvorak himself, and the best-documented experiments, as well as recent ergonomic studies, suggest little or no advantage for the Dvorak keyboard.”

Far be it from me to tell anyone what layout to use, but personally I see no reason to attempt to switch to Dvorak.

—

I’ve already linked to my response to that steaming pile of researcher malpractice, which is here. -rc

Many, many (shhhh) years ago I became a Linotype operator. At almost the same time, I learned the qwerty keyboard. Although I learned the Linotype keyboard after the qwerty, I was always faster on the typesetter. In fact, I was considered (and paid for) being a “gun” operator.

Made a lot of money then. More than I made for being able to use the typewriter keyboard.

Oh, yeah, a footnote: the Linotype keyboard layout was the secret in the different speeds between the two.

—

The Linotype had its own layout also based on frequency of use, with a lot of other special keys for typesetting — a total of 90 keys. You can see a photo of its keyboard here. -rc

I read one of Dvorak’s books years ago, and I believe in the superiority of the system. Indeed the superiority is so obvious, that all of the critics settle for asserting that Dvorak’s system is not enough better to be worth the changing over. They minimize the advantages and greatly exaggerate the impediments to changing.

I wonder if you can explain a specific detail that I am curious about — the positions of u and i. Since both of these keys are struck by the index finger of the left hand, it seems like the more frequent letter ‘i’ should be in the home position, rather than ‘u’. Your mention of the easier motion of pinky finger to index finger mad me wonder if this might be a factor, assuming the combination ‘ui’ is more common than ‘iu’. I don’t know if it is, but given how relatively slow it is to type two different keys with the same finger, I would think that the letter frequency would be more important.

Still, Dvorak must have had some august reason for choosing the positions of these two letters. Can you explain it?

—

An “august reason,” eh? 🙂 The reason for any particular key being assigned to any particular finger is discussed in detail in the book Typewriting Behavior (which is available through my shopping cart) by August Dvorak, et al. Briefly, they were “loading” each finger based on its “skill” (strength and dexterity). “…[T]he ‘universal [keyboard]’ finger loads rather shockingly deviate [from their ability]. For the ‘simplified’ keyboard, the ranks of each stroking load assigned each finger exactly follow the ranking for each finger’s ability” (p220). Believe me, they go into excruciating detail as to every specific factor that goes into the design — which is why the book is more than 500 pages. -rc

I switched to Dvorak back around the turn of the century, and contrary to my expectations I have not been able to switch back and forth freely. As a computer contractor I move from job to job frequently, and each time I start out slow until I can configure the PC at my new location to Dvorak. I’m not helpless in QWERTY, you understand, just very slow.

But here’s the thing: Even years after switch over, once in a while after pausing briefly in my work I type a word and it comes out garbage because my fingers were typing in QWERTY! Usually I’m looking at the screen while I type so I stop instantly, assuming my fingers are off the home position; therefore it lasts no longer than a single four- or five-letter word. But it always causes me to laugh in wonder at the complexity of what must be going on in my brain.

By the way, I have never understood one assertion, that it’s easier to drum my fingers from the outside in rather than the other way. I’ve always drummed my fingers from index to little finger, and when I try it the other way (as I did just now while reading the article) it’s just wrong. I guess I must be wired differently from the rest of you.

—

Several others have made the same comment. I’m sure that it is true for the majority of the population, but that leaves the rest, for which it’s not true. When I update my own Dvorak book, I’ll be re-researching that whole aspect to see just how much of an effect they thought it had. -rc

I’m a writer & editor who’s been using Dvorak happily for almost 30 years. Keyboard fatigue is non-existent with Dvorak. I do make it a point to type on other people’s Qwerty machines once a month for a little while, just to keep my Qwerty touch typing from getting too rusty, for those rare times when I need to use a Qwerty keyboard and it’s inconvient to switch it to Dvorak. All I can say for the skeptics is, if you don’t want to use Dvorak, that’s your choice, but don’t penalize future generations by knocking it — it absolutely should be the standard keyboard taught in schools. (And does Bill from Indiana have any actual facts to back up the conclusion he so eagerly quoted?)

—

People who learned Qwerty have a vested psychological interest in knocking Dvorak: it means that their own learning is not invalid. It’s not; people CAN type on Qwerty. But surely they remember how difficult it was to learn — difficult, and horribly boring. They suffered, so they think others should suffer too. Sad, when there’s a better, easier, faster way to learn keyboarding. Why not get that out of the way so students can get on with what they’re using the computer for, rather than spending so much time learning how to type?! -rc

Where can I get a Dvorak keyboard for my Mac?

Thanks!

—

It’s already there. Just activate it. -rc

Just to let you know Dvorak is not only built right into Windows and the Macintosh operating systems, but also in Linux, so everyone can give it a try!

—

Yes, the conversion page I linked to in the last reply has info for a variety of systems, and I’ll update that when I get solid and clear info for others. -rc

I tried out the Dvorak keyboard for a while. Not too hard, my being a Mac user and a touch typist. My typing speed began to approach what I had achieved on the QWERTY keyboard, but I encountered a problem that I found impossible to overcome.

Every time I used a keyboard shortcut for a menu command, I was getting the wrong result.

Undo (Command-Z), Cut (Command-X), Copy (Command-C), and Paste (Command-V) are all in a row, right next to the Command key (left {as well as right} of the Space Bar) in QWERTY. Muscle memory trained me to hit the same keys whenever I needed those.

It didn’t take too many attempts to ‘Cut’ text that caused a ‘Quit’ box to show up for me to stop trying to use the Dvorak keyboard.

—

You can leave the Command- (or Ctrl-) key strokes in the same physical location, but I do think that’s got its own problems and confusions. It’s best to learn the layout you’re on fully. Yeah, my cut/copy/paste are not across the bottom of the keyboard anymore (and I almost always use the keystrokes, not the mouse clicks, to accomplish those functions), but I don’t consider that a handicap. -rc

I had no idea you had debunked the paper to which I referred in my previous comment. I apologize for being too lazy to click to your Dvorak Keyboard site and look around a bit. When I read the paper a few days ago, having not looked at it for months, I realized it seemed pretty poorly written.

Keely in Pennsylvania,

That line I quoted was, I imagine, one of the most critical conclusions about the Dvorak layout that was presented in the paper. I did include a link to the full paper in my post, but I guess for obvious reasons it wasn’t included in my comment.

In general, I suppose it’s just inertia for me that makes me not want to bother switching. I get about 80 WPM on Qwerty, and since I don’t write for a living (or indeed, write much at all), I don’t really have a desire to be faster. Kudos for all those who have improved their speed–while I can’t rule out trying Dvorak some day, it’s not for me right now.

I have four keyboards memorized, although they are basically all QWERTY – English, Spanish, Portuguese and Italian. Many of the keys change for accentuations. In Spanish and Portuguese there is a stop-key with the diacritical character for use prior to the accentuated vowels and separate keys for the ñ, ¿, ¡, ç, etc. In Italian there are separate keys for the vowels with accents, all in one: è, ù, à, ò, ì. Are these international characters available on a Dvorak keyboard? I spend at least 75% of my keyboarding time doing it in one of these other languages!

—

Dvorak can be adapted to accented and special characters as easily as Qwerty. -rc

Jacira says that I have four keyboards memorized, although they are basically all QWERTY – English, Spanish, Portuguese and Italian. Many of the keys change for accentuations. In Spanish and Portuguese there is a stop-key with the diacritical character for use prior to the accentuated vowels and separate keys for the ñ, ¿, ¡, ç, etc. In Italian there are separate keys for the vowels with accents, all in one: è, ù, à, ò, ì. Are these international characters available on a Dvorak keyboard? I spend at least 75% of my keyboarding time doing it in one of these other languages!,can anyone comment on this?

—

The Dvorak layout can be adapted to accented letters as easily as Qwerty, and the benefits of the layout apply to all languages which use the Roman alphabet. -rc

I have a slight disagreement with Randy’s comments to Jacira and Lopez on typing accented letters with the Dvorak keyboard layout. While I favor the Dvorak keyboard and think accented letters can be accommodated successfully, the perverse inefficiency of the QWERTY keyboard does have an impact on typing accented letters.

With QWERTY, several rarely-used keys are within easy reach on the right side of the keyboard, and one, the semicolon, is a home-position key, under the little finger of the right hand. This makes the semicolon a natural key to use as a dead-key for typing accents in QWERTY, while the brackets and apostrophe may also be used. Dvorak places the frequently needed characters on the most easily typed keys. This is very valuable, but it means that keys available for accents are harder to reach. The semicolon is on the left hand, as are the vowels that would most frequently be accented in European languages. This could lead to key sequences using the same finger, which the Dvorak system strives to avoid, although they are commonplace in QWERTY. In spite of this drawback, I still use the semicolon as my dead-key for Dvorak, since I judge it to be the most convenient key. This works well for two of the languages that I type frequently, Spanish and Esperanto, since these only have one accent per letter (excepting the rare ü in Spanish). For Portuguese, French, and other languages that have multiple accents for some of the vowels, you need either multiple dead-keys, key combinations such as Option-c, or some sort of keyboard macro utility program, such as TypeIt4Me. I prefer the keyboard macro utility for languages that have more than one common accent per letter.

You can create your own custom keyboard layouts for the Mac using a nice free utility called SIL Ukelele. There are probably similar utilities for the PC.

Since the essence of the Dvorak layout is a keyboard layout attuned to the letter sequence frequencies of a language, there would be an advantage to creating a different layout for each language. But if the Dvorak keyboard for American English is little known, variations optimized for other languages are even more obscure. In any case, the segregation of vowels and consonants is a big plus for every European language, and the distribution of consonants for most European languages are similar enough to make the Dvorak layout worth a try.

I don’t think my question was clear before, as it appears that none of you are familiar with other language keyboards. The location of the “stop” key or “dead” key as you call it for the Spanish QWERTY keyboard is the key that has a left parentheses and left bracket. When I type in Spanish, I simply hit that key, then the vowel that I want to accentuate and it appears accentuated in the text. The semi-colon key is the “ñ” and in Spanish to form the semi-colon or colon it is a shift plus a comma or a shift plus the period. I find this very easy and this is how the keyboards actually look in Latin America and/or Spain. The Italian keyboard is much more complex and a bit cumbersome so my question is really can I set up something similar with the Dvorak keyboard or does one already exist for Spanish, Portuguese and Italian which are the languages I use on a daily basis? (I’m a technical translator and simultaneous interpreter.)

—

My original reply to you was, “Dvorak can be adapted to accented and special characters as easily as Qwerty.” I’ll expand on that: Qwerty keyboards have been adapted with the addition of special characters used in computing ( > < \ | ~ and more), languages (dead keys and accents), “Return” and “Control” and “Alt” keys, and lots more. Simply, the arrangement of the Dvorak letter keys is different. I don’t see how starting with Dvorak is any different from starting with Qwerty for such applications. -rc

Responding to Jacira, I type regularly in four languages, English, Spanish, Esperanto, and Portuguese. I use French less often, and Italian rarely. I support three language departments that cover about 12 languages, eight of which use a roman alphabet. So I do have some background in the question of foreign language keyboards.

The standard QWERTY keyboard layout was an attempt to deal with mechanical limitations of more than 100 years ago. While it may have been a clever idea in its moment, it is sad that we continue to suffer from limitations that disappeared a century ago. European language keyboards take the limitations of the QWERTY layout, onto which they graft on a few minor changes (eg. AZERTY) and add additional hacks to deal with the needed accented letters and special characters. Again, in their moment of invention, these may have been good compromises, but it is continuing folly to use a keyboard on a computer that retains the limitations of 19th century mechanical technology.

People resist change, so all the computer keyboards for different languages and countries have mirrored the mechanical layouts of the typewriters that preceded them. An individual has the option of following the herd or making a more rational choice. While computers come with dozens of keyboard layouts identical to different national layouts, this doesn’t meet the needs elegantly of, for example, a Denver-based language professional working daily with multiple languages. Why should that professional try to learn, use, and maintain facility in four different national language keyboard layouts to do their work (aside from hubris)? This can only decrease speed and increase the error rate.

It makes more sense for the multi-lingual person to use a keyboard layout for every language that is as consistent as possible. Computers make this possible to a greater extent than mechanical systems ever could. Jacira mentions that the semicolon key is used for the ñ in many Spanish keyboards. This means that a QWERTY home position key is dedicated to a letter which has relatively low frequency. On a computer, a user can create a keyboard where the semicolon key is the initiator (dead key) for the accented letter version of all the vowels, the ñ, ç, and the upside-down question mark and exclamation point. This increases the frequency of use for that key by a factor of ten, and justifies it as a home position key. It means that every special character for Spanish (except ü) is initiated by exactly the same keystroke, which increases speed and accuracy. The semicolon can be used as the primary initiator/dead key for the accented letters in every other language, giving the multi-lingual typist more consistency as they change languages. But we needn’t stop there.

Jacira mentions that a standard Spanish keyboard layout moves the semicolon and colon to shifted positions of the comma and period. Again, this mirrors the national language mechanical typewriter, but for someone typing today, it makes sense to question whether this is the best compromise. Because of computer terminology and the web, a modern typist will use the angle brackets, forward slash, and colon vastly more than anyone ever did on a typewriter. The chosen keyboard layout should reflect that.

For typing languages where the same letter can have multiple different accent marks (á, à, ã), the standard keyboard shows increasingly aggravating limitations. There is no elegant and efficient keyboard layout for French, Italian, or Portuguese, because there aren’t enough different keys within easy reach of the fingers to create fast and effective keyboard layouts for those languages. Yes, humans have adapted to antique mechanical limitations, but that doesn’t make them good solutions.

The best solution by far is to adopt a new physical keyboard layout, one which has a more ergonomic placement of the keys, and which offers the left thumb (which normally does nothing) two or three programable meta keys. With this sort of physical keyboard, all the accented letters and special characters for every language using Roman characters can be typed using a consistent, elegant, multilingual keyboard layout. This kind of keyboard really makes the advantages of the Dvorak layout shine, and improves the typing speed for all languages. Yet surprisingly few people are ready to invest a couple of hundred bucks in an accessory which would improve their lives every day.

The next best solution to typing in languages with multiple possible accents on a letter, is to use a keyboard macro application, such as TextExpander or TypeIt4Me. (Of course, it is possible to use these utilities with the above mentioned physical keyboard). These programs vastly extend the possibilities for contextual interpretation of keystrokes. With this kind of utility program, it is possible to make elegant keyboard layouts and typing strategies for Portuguese, French, Italian, Navajo, Vietnamese, and other languages that use the Roman alphabet, and to make them fairly consistent across all the languages that an individual uses.

For any of these approaches, using the Dvorak layout as the basis for creating a multi-lingual keyboard will lead to a superior, quicker, and more accurate method of typing.

—

Thanks, Derek, for a very interesting expert’s perspective! -rc

Thank you, Derek, for taking the time to give me that detailed response. Are you in Albuquerque? Do you work at UNM? That’s one of my alma maters and I get back there to visit friends fairly frequently. If possible I’d love to see the configuration you have created and discuss this in more detail. Randy – is there a private way you can put Derek in contact with me? Feel free to provide him with my email address.

Thank you! Gracias! Grazie mile! Muito obrigada!

—

Derek is a long-time reader (as I know, you are!), and I’ll forward your address to him. -rc

Colemak. The benefits of Dvorak, but an easier transition from QWERTY. Once my Typematrix keyboard arrives, I begin the transition in earnest and hope to reach speeds of 130-140.

—

I had little difficulty transitioning from Qwerty to Dvorak. There are two difficulties in learning to type: the physical dexterity, and the layout. Changing to an absurdly simple layout like Dvorak is easy, and the physical dexterity needed is less with Dvorak, so if you could do the high-level gymnastics required by Qwerty, the effort on Dvorak is a piece of cake. -rc

The developer of Colemak doesn’t reveal his research methods and assumptions, although he gives some hints. Dvorak describes in great detail his research, experiments, and reasoning. His layout was very carefully tested. It’s possible, but unlikely, that Coleman has come up with something better, without doing in-depth research, and seemingly without reading Dvorak’s research.

The primary advantage given on the Colemak page is erroneous, in my opinion, on two counts. Coleman says that greater similarity to QWERTY is an advantage, because it makes the transition easier. The fallacy is that the transition from QWERTY to Dvorak is difficult. If I remember the Dvorak research correctly, the average, not very good typist (<40 words per minute) can switch to Dvorak and equal or exceed their previous typing speed in less than ten hours of use. For a better typist (40<x<100), it may take twenty hours of practice with Dvorak to equal or exceed the previous QWERTY speed. Obviously, individuals differ, but Dvorak’s averages were taken from large samples of users. My point is that the transition takes less than a week for almost everyone, so it is unimportant if transition to Colemak is slightly faster. What matters is the results that users obtain after the short transition period is complete. Until we have reliable tests of Colemak vs. Dvorak, it will be hard to judge.

However, I doubt that it is, in fact, faster to make the transition from QWERTY to Colemak. The similarities are an advantage only in the very short term. After a few hours of practice, systems that are too similar are a source of error, since it is harder to maintain mental and muscle memory distinctions, for systems that have significant overlap. If a person makes a complete shift to Colemak (or Dvorak), then that person will learn either system quickly, and confusion will be minimal. But if you regularly shift back and forth between QWERTY and another system, as you must if you regularly use keyboards/computers belonging to other people, then similar systems will cause more confusion.

The question of key combinations used in computer games or other computer tasks is an interesting one, and worthy of more investigation. Coleman talks about single finger movements and “excessive strain on the right pinky.” Dvorak researched the key factors in typing speed, and concluded that two letter sequences were the most important. His layout is not simply optimized for single letters, but for letter sequences. I think strain of the pinky was a significant question with mechanical typewriters, but I have doubts about it on a computer keyboard, where the needed force and range of key travel is minimal.

The physical layout of the standard keyboard is un-ergonomic, especially for the left hand. The QWERT keys of the upper row for the left hand, (or those in the same position for Colemak or Dvorak), should be shifted to the right, while the bottom row of keys for the left hand should be shifted to the left. This would follow the natural shape and position of the hand. Such keyboards exist, but they are rare.

Derek, thank you for the reply, as I didn’t know these things, but please be aware how one could interpret it as steamrolling. I may well try Dvorak first, then.

I’m not sure I get the steamrolling. As I see it, there are complex questions involved, and I try to be thorough. I think Dvorak did good work, but it is reasonable to think that improvements could be made. However, sorting out the improvements from the dross is difficult, without careful, large-scale testing, which no one is in a position to do. Perhaps in a few more years, voice recognition will be good enough that keyboards will no longer be used.

For some reason, a piece of my previous posting disappeared.

—

Ah: you used < characters, which browsers are interpreting as commands. Fixed. As for the content of your post, heck: even I learned some stuff. Thanks! -rc

I am very interested in the Dvorak system. However, I’d like to know if when using it you can still email people and blog or do you have to switch back to qwerty?

—

Dvorak isn’t a “system”, it’s simply a different keyboard layout. It enables you to type faster and more accurately (after learning to type more quickly). Once you have it on your computer, you use it to type anything you wish, just like with any other keyboard. -rc

The Dvorak keyboard is a brilliant option if you’re typing in English.

I use the Canadian Multilingual Standard layout because I frequently type in both English and French. When you’re typing in French, it’s a huge advantage to have just one keystroke for “é”, “è”, and “à”. Switching between keyboard layouts would be a horrible pain so this is a nice bilingual compromise for me. I like that we don’t have to limit ourselves to the standard offerings. There are a lot of alternatives out there to suit everyone’s circumstances, including the Dvorak layout.

—

English isn’t required for Dvorak: it works nicely for any language using the Roman alphabet. It accommodates dead keys as well as Qwerty does, but I’d have to look at your keyboard to see how it does accented characters with one keystroke. -rc

Even my Qwerty keyboard does this when I switch it to Italian — the accented vowels have corresponding keys, in upper and lower case. Not so with my Spanish and Portuguese layouts, however. They have an accent key that is a stop key which you hit before the vowel.

I taught computer use and futuristic computer topics in the 90s. I used to explain that we had really missed an opportunity to switch to DVORAK with the advent of personal computers. I thought that for a long time then I realized that this was a bit short-sighted. In the future, we will not peck keys. We will speak to our computers and eventually think to our computers. We are doing it now.

—

“Can” and “do regularly” are two very different things. We’ll be dealing with keyboards for some years to come, I’m afraid. -rc

I have often read about the ability to type large numbers of words on the home row, up to 5,000 on a SDK and 300 on a Qwerty.

But in trying to find some method to support those numbers, I constantly fail to get numbers that high.

Using an anagram word finder on the Internet, I get 81 for a Qwerty and 714 for a Dvorak.

So I used the same online sources to take another look at increasing the home row ability, to add more words for a little extra action.

I have been using a Dvorak keyboard for the last 7 years after suffering RSI injuries to both hands.

Looking at the SDK I noticed that the -/_ key on the right hand side could be replaced with an additional letter, taking the home row from 10 letters to 11.

Using the figures for the Qwerty and the SDK, the SDK has 8.8 times the available words, if you add the letter R you move from 714 to 1733, and that increases home row from 8.8 times to 21.4 times the number of words that can be typed on a Qwerty.

I’m still looking for the source of the quoted number counts for Dvorak and Qwerty, can you point me to them?

I will continue to work on keyboard to see if any further increases in the word count are possible, it does move your hands out by one key on the right hand side.

I dropped the R to the right of the S, the — replaced the Z, the Z replaced the V, the V replaced the W, the W replaced the M and the M took the open space from the R. I don’t think this layout is perfection, but I’ll play with it some more and see what I can come up with.

I used the Microsoft Keyboard Layout Creator, and changed the SDK layout, then popped the keys off both my laptop and desktop, and had them working on the new layout in 25 minutes om so.

Compared to the time it took to retrain from Qwerty to Dvorak, the jump from Dvorak to the new layout has been pretty painless, I don’t have full speed back yet, but I don’t think it will take all that long.

Do you have any thoughts?

—

You’re concentrating too much on one aspect of the design; optimizing for that one aspect negates the value of others, such as inboard stroke flow, which optimizes sequences to conform with the physiology of the hand, for one example.

The list of home-row words I have was created by computer program running against a computer-based dictionary/word list, and it came up with 4,383 words — and that was some time ago, so no idea how complete the dictionary/word list actually was. I don’t have the list to count, but the same program run on the same source file for Qwerty was something like 300 words.

The best reference on exactly how the design was created and the many aspects that went into it is the report by Dr. Dvorak and his colleagues, Typewriting Behavior. It’s a must-have reference for anyone trying to improve a keyboard’s layout. -rc

@Chris in Utah, As Randy mentions, obsessing over home row words is focusing on something of secondary or tertiary importance. Dvorak and Dealy spent a fair amount of research time looking at what are the most important factors in typing efficiency. This is a question more complex than just speed. They took into account how the hand moves, and how each finger can move easily, as other fingers move toward other keys. They wanted to reduce fatigue and injuries, as well. They found that greatest efficiency isn’t found by analysis at the word level, nor even at the three letter sequence level. Rather, they discovered that the frequency of two-letter sequences was the key that unlocked greater efficiency at other important levels and of many other factors. Therefore, by optimizing the keyboard for this critical element, they could also optimize other factors.

In any case, with only ten or eleven letters in the home row, even though you can type many different words, you will not be able to type many interesting English sentences using only the home row. And it hardly matters how many obscure words can be typed via the home keys. It’s much more important that common words be easily typed. The large number of words that can be typed in the home position using the Dvorak keyboard is a secondary effect of optimizing what really matters. I am skeptical that making changes without any research could lead to overall improvements. I think it is more likely that changes improving one index, such as the number of home row words, would have negative effects on the efficacy of general typing. And it might increase the number of repetitive stress injuries.

Quite an interesting article. I do like my QWERTY keyboard, and seem to be able to type on it about as fast as you type on DVORAK… So I can only imagine that I’d be going hella fast on DVORAK. 😛

I think the biggest problem DVORAK faces isn’t anything related to the layout, it’s the users. DVORAK is the less popular alternative. And a lot of people who use it, because it’s less popular, get on the offensive about it. It’s a great system, but I honestly have pretty much determined I’ll never use DVORAK because of the people who insult me for NOT using it. I just object to it on the basis that.

Of course, I’m not saying YOU’VE done this at all. You provide good, reasonable arguments about it. You don’t say “You should switch,” and you seem reasonable enough that if you did, and I said, “I don’t wanna” you’d respond, “Okay, no problem.”

But there are a lot of people who are bringing it up when it’s not wanted or relevant, and that hurts the possibility of it being adopted as much as the force of people not liking change does.

—

Yes: fear and stubbornness on this is silly. You’re right about what my answer would be. It’s not simply a matter of speed: I use Dvorak because it’s easier to be fast and accurate on Dvorak than Qwerty. Throw in the less likelihood of repetitive strain injuries and it’s a winner for someone like me, who types a lot, 7 days/week.

Getting people to switch isn’t on my agenda, but those having trouble with Qwerty should at least investigate Dvorak as an alternative. My “trouble” was hitting a 55wpm plateau, which was an issue for a full-time writer, so (especially when adding accuracy and health issues) switching was smart. My agenda is much more focused on people who don’t know how to type yet: it’s ridiculous to teach Qwerty in schools when Dvorak is so much easier to learn! It used to be the excuse was, “Well, the typewriters in the workforce are Qwerty.” Yeah, well, there are no typewriters anymore; computers can be switched to any layout for no cost. So the excuse now is…?

But meanwhile, there’s that fear and stubbornness. You don’t seem to have fear, but I see a lot of stubbornness in your comment. Is that holding you back, keeping you from the best option for you? Only you can answer that honestly. -rc

I am a multi-lingual web developer and routinely switch between Spanish, Portuguese and Italian keyboard layouts. Are the foreign diacritical characters available on the Dvorak keyboard layout (accents, Ñ, ç, etc.)? If so, where can I find instructions to load the Dvorak keyboard layout into my Windows 7 computer?

—

Indeed, what’s built into Windows is English-based Dvorak. There’s nothing about Dvorak that would make it any different to the use of “dead keys” to allow for the typing of accented characters, as with Qwerty. But setting that up is a difficulty, and — I believe — beyond what is provided within Windows. I can’t believe this hasn’t already been solved, however, and if I needed that, I would spend some time searching for solutions already published online. Since I don’t need it, though, I can’t even begin to suggest where to look. -rc

To Jacira, I did find something for Spanish [broken link removed].

You probably won’t find a standard solution built in to operating systems, but if you’re willing to add customised keyboard layouts, Google will help you find what you need.

—

Cool! Thanks much. -rc

I don’t think that keyboard layouts using key combinations for typing accents, such as [Alt-E], are a good solution for anyone regularly typing in a foreign language. An average typist using the Dvorak layout will be typing eight to ten letters per second, and the best typists will double that speed. Typing an Alt-key combination takes four to ten times as long. Therefore, using a dead-key (meta key) approach of two sequential keystrokes to create an accented letter is much faster than typing a key combination. It is also much easier on the hands/fingers/wrists than requiring at least one finger to move far from the home row, and fingers from both hands to strike the needed keys in parallel, that is, simultaneously, with precision timing.

As mentioned when Randy, Jacira, and I chatted about this earlier (see January 2011, above), some languages, such as Spanish, German, Irish, or Esperanto, can produce all the needed accented characters with single meta-key (dead-key). Other languages, such as French, Italian, and Portuguese, place two or more accents alternatively on the same letter. In this case, the best and fastest solution by far is using a custom keyboard layout with the type of ergonomic keyboard which has multiple meta keys for the left thumb, (a dextrous digit which does nothing on a standard keyboard). Note that most so-called ergonomic keyboards do not correct the misalignment of the upper row for the left hand. There are a few companies that take ergonomics and repetitive stress injuries seriously. The first link below is to a keyboard that is switchable between Dvorak and QWERTY. These keyboards cost $300-$1000, which makes sense for any professional, or anyone concerned about repetitive stress injuries.

The next best approach is to combine a custom keyboard layout with a keystroke macro program, such as Typinator, TypeIt4Me, and the like. I haven’t used it, but the free, open-source AutoHotKey for Windows says it can do this.

There are various programs that allow anyone to create custom keyboard layouts. A free one that I use for Macs is Ukelele. For Windows, AutoHotKey lists this capability, as well.

I haven’t yet found anyone distributing a good Dvorak multi-lingual keyboard layout, but I have created several over the years that I find useful, using programs like those mentioned above, and it wasn’t difficult to make a few modifications to the standard Dvorak layout to allow easy typing of the needed diacritical marks.

—

Thanks again for your expertise in this area, where mine is lacking. The first keyboard in your list is made by Kinesis-Ergo, and is the (newer version of the) model I use. Even though it’s Dvorak-Qwerty switchable, I leave it in Qwerty and use Windows’ built-in Dvorak layout. That does result in a few oddities (the “-” key actually gives me “[“, for instance), but I’m quite used to that. -rc

I do a fair bit of writing and photoshop work, and for writing, Dvorak seems to me (at one day of training) clearly superior. However, for Photoshop, I don’t think it’s worth it to change all the keyboard shortcuts. So it looks like I’ll be using two keyboard layouts and switching when necessary. I have to say though that I really do want Dvorak to be better for me than QWERTY. QWERTY is just horrendous for how much jumping around I have to do.

—

Indeed so. As a writer, I love how fast I can type, how accurately I can type, and come away at the end of a long day without sore hands. Using two keyboards isn’t as daunting as you may think: I use Dvorak on my computer, where I touch type, and Qwerty on my smartphone, where I type with a finger or two. (I did try Dvorak on my phone, and hated it: if I can’t touch type and “have to look” anyway, Qwerty is the keyboard I use since I’m used to looking at it.) The bottom line is whatever combination works best for you. -rc

I’m glad to hear that Megan has discovered Dvorak, and finds her experience with it positive. I’m not sure I understand her Photoshop concerns and preferences. Perhaps this is also a question where Windows and Macs are dissimilar, or perhaps Photoshop enforces some differences. I use a Mac, and I find that the key combinations that I use in Dvorak follow the named combination within the Dvorak system, rather than maintaining a QWERTY physical positioning. In other words, Command-A, Command-N, Command-T, etc are typed as described — you press and hold the Command key, and then tap the combining letter, wherever it is on that Dvorak keyboard layout. If I am thinking in Dvorak layout, I don’t have to remember where the letters would be on the QWERTY keyboard layout, I just hold the needed modifier key, and type the same letters in the same positions as I would for typing text with Dvorak. This is the way that I want it. I think in terms of “Command-C”, “Option-U”, etc, and the manuals and instructions all use those terms. So for me, this is straight forward.

However, some people want to maintain the same physical position for the key combinations. For example, they want the copy command on Dvorak-Mac to be the Command key plus the third key from the left on the bottom row, where the C key is in QWERTY. In other words, when they type a key combination, they want to temporarily have the QWERTY keyboard back. Apple offers a keyboard that does this, partially. They call it “Dvorak QWERTY *”. This gives you the Dvorak keyboard, except when you are pressing the Command key, at which point it gives you QWERTY keyboard, only as long as you hold the Command key. Then it goes back to Dvorak.

I suppose that this is useful for some people, but I think it is rather odd. If I wanted the key combinations to be in the same physical locations as in QWERTY, then I would want ALL the key combinations that way. Apple’s Dvorak QWERTY * keyboard layout only affects the Command key, while the Option and Control keys are still in Dvorak. That seems like a weird mixture to me. Hopefully, there is something similar, or better, for Windows and Linux, for those who want that.

Using a keyboard layout creation program, it would be easy to create a Dvorak keyboard that retained the physical QWERTY positions for all key combinations with Command, Option, and Control keys on Mac, or Control, Alt, and Windows keys on PC. If this is what you would like best, Megan, take a look at the keyboard creation programs/links discussed at the bottom of my March 15, 2012 posting above.

I agree with Randy, that switching between Dvorak and QWERTY is not that difficult, but I prefer not to.

—

I’m not a Photoshop user, so I don’t really know what the issue is, but I suppose it is similar to the idea that some people are very used to (for instance) Ctrl-C and Ctrl-V (Copy and Paste) being in a specific location on the keyboard. To some, it’s not “Ctrl-C to Copy” but rather “Copy is THIS key combination” — it’s immaterial what letter is used (“V” doesn’t really have much to do with “Paste”; it’s merely next to the C on Qwerty). It’s more about muscle memory than any logic about what letter is involved. -rc

I was just poking around my Win 7 Control panel where I go to add languages to my keyboard layout and noticed that there is now a built in option to select the Dvorak keyboard layout. There are also two others under English, United States: Dvorak for left hand and Dvorak for right hand.

What is that all about? Can you type with only one hand with the Dvorak keyboard? Can you type with one hand tied behind your back? 😉

Also a note to Megan, I switch keyboards all day long and have memorized the location of the different keys depending on the language. It is a simple LEFT ALT plus SHIFT to switch between languages, which is pretty easy. I am also a Photoshop Professional and find more of a problem finding the correct key combinations for Photoshop when I’m in Spanish or Portuguese, especially for zooming in or out (ALT + to zoom in, ALT – to zoom out in English) as the plus sign gets buried and is much harder to find. Still, once you know where it is, it isn’t that much of a detriment to work flow.

—

Dvorak — including the one-handed variants for amputees — has been in Windows since version 3.0. My Dvorak site’s Conversion Page has had instructions for years. -rc

Indeed the shortcut issue is to me minimal. I don’t know why you would particularly want to have the control key layout different from the typing layout. I mostly use Dvorak, but on occasion use qwerty a bit. No issues there.

Much more at issue on shortcuts is that I have things like C-n (down a line) C-p (up) C-b (left) and C-v (page down) fixed quite firmly in my brain thanks to use of emacs, with sometimes interesting results in other programs. Indeed, this has led me to use first the Firemacs extension for Firefox, and now I use Conkeror as a browser (which also allows me to very nearly dispense with a mouse for web browsing in a full graphical browser).

I have been able to easily switch from Qwerty TO Dvorak in English using Microsoft XP OP. I can’t figure out how to easily make the accents and ñ required for spanish on the Dvorak keyboard. With the Qwerty keyboard I press the ALT key and the letter. I’ve tried to accomplish this several times with no success. I really love the Dvorak keyboard, which I had learned years ago before I knew about the switching that can be easily done. Thanx in advance.

—

Whether you can get accented characters is not dependent on the Qwerty or Dvorak key arrangement but rather the software implementation of the layout you choose. For instance, Windows doesn’t just have plain “Qwerty” but rather “US-English” (and many, many other variations on Qwerty). And it doesn’t have “Dvorak enabled with dead keys for the typing of accented foreign characters” but rather “US-Dvorak” — specifically for American English use. I have no idea how to modify it for foreign language use since I’ve never needed that, but the Dvorak layout is pretty well optimized for any language that uses the Roman alphabet, even though it was specifically designed for English. -rc

I agree with Randy, that dead keys are the first step to typing foreign languages efficiently on any computer keyboard. In most cases, you have to make your own virtual keyboard layouts for foreign languages, because computer companies have never understood foreign languages (nor user efficiency). For Windows, try the free AutoHotKey program. It is supposed to make creating your own keyboards easy. I use Macs, and the free Ukelele keyboard creator works very well for me. SIL.org also has some keyboard creation tools for Windows, at least through Vista. I didn’t see anything for Windows 7 and 8 in my quick look.

Spanish is easy, because only one accent mark appears on any letter, with one rare exception*. Make the semicolon key your dead key, but only before the vowels, ‘n’, the exclamation point, and the question mark. For all other characters, create your virtual keyboard layout so that the semicolon gives you the character that you type next (usually a space). Create your keyboard so that semicolon before a vowel will give you that vowel with an accent mark. Semicolon before ‘n’ will give you the ‘ñ’. Semicolon before ? and ! will give you ¿ and ¡. You can create all of this, based on the Dvorak keyboard, in about ten minutes, once you understand the keyboard creation system. You will be amazed at how effective this typing system will be for typing Spanish.

Another advantage for this approach is that you don’t have to switch keyboards between Spanish and English. Everything that you type in English on this keyboard will come out just as you are used to, while everything in Spanish will be easily accessible, too.

*In Spanish, the letter ‘u’ can have two diacritical marks, ‘ú’ and ‘ü’. I suggest creating your virtual keyboard, so that semicolon followed by ‘u’ gives you ‘ú’. For the rare ‘ü’, either memorize the Alt-key number code, or create a second dead key. On the Mac, use the key combination [Option-u] followed by ‘u’. I find key combinations much too slow for regular use, but they are tolerable for letters that only show up once a day or less.

—

Thanks, Derek! Very helpful info. -rc

To Carl in Maryland:

If you are still using Alt key combos to get the ñ and the á, é, í, ó, and ú, or even the ü and ¿ and ¡, you are wasting a TON of time. In XP, with the Qwerty keyboard, you need to set your languages by going into the Control panel, selecting Regional and Language Options, then click on the LANGUAGES tab, click DETAILS and click ADD, then select the language from the list. Be sure to click in the box for KEYBOARD LAYOUT as well. Then you just need to figure out what is under your key caps!

Once you use if for a while, it is easy.

You can make yourself a “cheat sheet” by doing it in a Word document, and clicking on each key, then doing it again with Shift plus the key, etc., then print it and tape it next to your desk!

Reading this and then examining the Dvorak layout quickly convinced me to try it out. It sounded like a good idea; I’m in my 20s and already wear wrist braces on occasion because I love to write and joint problems run in my family. It seemed like a great idea.

In my first two hours, I could touch type 15wpm, 95% accuracy for base keys! I found some great online learning programs as well as suggestions on how to learn quicker, including an article about how to learn it in a month.

Thought I might as well share some of those links on learning Dvorak, which are designed with the layout of the keyboard in mind.

My favorite has to be learn.dvorak.nl/ which even allows keymapping so you don’t have to switch your keyboard over before you start practicing. It divides up the full alphabet into 8 lessons, although it doesn’t include learning punctuation. I figure after learning the alphabet, the punctuation shouldn’t be too difficult.

Another great one would be gigliwood.com

Its lessons remind me of a standard keyboarding class. It’s more thorough, but also has quite a few more lessons but doesn’t offer the keymapping (at least not to my knowledge).

And finally, as I mentioned there’s an article someone made about learning the Dvorak in a month: [dead link removed].

Thanks for providing so much information on the Dvorak Keyboard, it really is fascinating information and knowing there’s something better is very helpful. I thought you may want to share these links as well for people making the switch so they have a free way to learn it.

Once I can spare the money, I’ll be adding to my personal library for sure! I just wish I didn’t have to wait, but my dog’s surgery put me on a tight budget for a while.

—

If you’re having trouble with your hands already, it’s indeed smart to switch to Dvorak for reduced impact. You might also look into dictation software to reduce keyboard use even more. -rc

You’ve rekindled my interest in the Dvorak keyboard. I couldn’t fit the Personal Typing course into my high school curriculum back in 1964. In 1981, with my first computer (Apple II), I concluded that I’d be spending an awful lot of hours at the keyboard in the future, and decided to teach myself to touch type. To my delight, it turned out to be easy — thanks to a program called Typing Tutor. It started you with key sequences, and then tested you not only by popping up letter sequences which you had to reproduce in a particular time, but with a game in which letters floated down from the top of the screen and you had to hit the appropriate keys to make them disappear before they hit the bottom (à la Space Invaders) — a really good way to squeeze the cognition out of the equation, and go from the letter to the hands. Within a week I knew the keyboard, and within two I was touch-typing everything at a reasonable speed.

Until recently, I had to be able to use other people’s computers (including my employer’s), and most of my writing is technical, composed in real time, so my maximum speed was fine. However, now that I’ve retired, you have me thinking that I should do it now — even if I only live another 15 years, that’s a lot of saved time, given how much computer work and communication I do (and given that voice dictation still hasn’t really arrived).

One obstacle has been to find a program as good as the one I used for QWERTY; on the occasions I’ve looked, I didn’t find anything. Learn Dvorak in a month? That’s way too slow. Luckily, Cassie provided some clues. Also, as it happens, the only thing I need to type faster for is on-line Boggle (wordsplay.net), and it occurs to me that that’s probably even better than the game for nailing down the keyboard once I’ve learned the key positions! Sorry I won’t be able to report on speed increases — I suspect maximum Boggle scores won’t count… 🙂 The only time I can reach maximum (and measurable) speed is in copying text, which is something I rarely do under normal circumstances.

P.S. — I was just looking at my QWERTY keyboard. 5 letters are dished, and the labels worn off — E, A, S, D, and C. If that’s an indication of frequency of use — and superficially, I’d think these are among the most used letters — it’s a bit odd that they’re all on the left hand (3 are home keys), when most people are right-handed. Two others are dished, with the labels (lower left corner on my keyboard) partially worn away — R and N; the latter is the only one of the 7 on the right hand.

And looking at the Dvorak layout — which I’ve never really studied — I note that A and S are under the pinkies in the home row; it seems odd to have such frequently-used letters under the weakest fingers.

—

Dvorak is based very well on the physiology of the hands, as well as languages based on the Roman alphabet. If you REALLY want to dig into why what is where, see the exhaustive report made by the team to the Carnegie folks who helped fund it: https://www.secure.thisistrue.com/product/typewriting-behavior/ -rc