In This Episode: When you follow your gut and push to be the best, amazing things can happen. James Flanagan did that, and the domino effect that followed is so amazing, you’ll find it hard to believe that one guy’s efforts are probably a part of your life every day — even though he’s been dead for several years.

061: The Domino Effect

Tweet

How to Subscribe and List of All Episodes

Show Notes

- Help Support Uncommon Sense — yes, $5 helps!

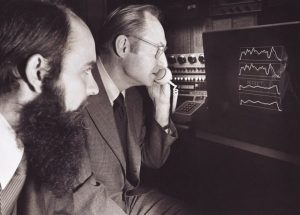

- See the transcript for a couple of photos of Dr. Flanagan.

Transcript

Welcome to Uncommon Sense, I’m Randy Cassingham.

James Flanagan was born on a cotton farm in Greenwood, Mississippi, in 1925. In high school, he was given a choice of two extra classes: typing, or physics. He looked up physics to see what it was: “the study of natural phenomena and how to use them,” so he chose that because he figured that could be helpful to a cotton farmer. It changed his life. At 17, he joined the U.S. Army Air Corps, where he wanted to be a pilot. He failed the color blindness test and was assigned to communications, where he worked on radar — and scrambling radio transmissions so that enemy forces couldn’t hear what someone was saying.

After discharge from the Army, Flanagan earned his bachelor’s degree from Mississippi State University in 1948 in electrical engineering, because of his fascination with the tools he worked with in the Army. He went on to earn his master’s and doctorate degrees in electrical engineering at MIT, studying at the school’s Acoustics Laboratory. He then joined the technical staff of the phone company — AT&T’s Bell Laboratories — in 1957, and in just four years rose to be the head of the Acoustics Research Department. This is a guy that, as he grew up, lived in a farmhouse that didn’t even have a telephone. Hell, it didn’t even have electricity until he was 12.

It makes sense that the phone company would want a whizzy engineer who understood acoustics, the branch of physics that deals with the study of mechanical waves, such as sound waves. With his rapid rise, you might get the idea that Flanagan was really something special. Well, and that he’s the subject of the Uncommon Sense podcast pretty much guarantees it!

Edward David Jr., the then-executive director at Bell Laboratories and later science advisor to President Richard Nixon, who actually survived Dr. Flanagan, said, “I hired him because of his interest in speech and hearing — and because he was a prize student. He brought a new look to the whole area of communications.”

Flanagan’s experience with scrambling radio transmissions was key to his career. In those days, it was difficult at best to understand soldiers’ voices on two-way radios — it’s not that great today! Then add in scrambling the voices, which at least was supposed to make speech completely unintelligible, which only is useful when the signal is unscrambled. The recipient has to be able to understand that voice clearly. In the 1940s, that was pretty darned hard. So no wonder he got the best education he could on the subject: clearly he saw challenges, and potential.

That potential was realized pretty quickly. By 1965 his book “Speech Analysis, Synthesis and Perception” came out, and became a leading textbook and reference book for anyone working in speech communications research. And in 1976, he wrote an article for the Proceedings of the IEEE — the main technical journal of the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers: the IEEE. The article: “Computers That Talk and Listen: Man-Machine Communication by Voice”.

“What is so significant about this article,” said Dr. Lawrence Rabiner, a professor of electrical engineering at both Rutgers University and U.C. Santa Barbara, who worked under Flanagan at Bell Labs, “is that it painted a picture of society in the 21st century” — 24 years before the 21st century arrived. And Dr. Rabiner said that in 2015, well enough into the 21st century that he knew how accurate Flanagan’s vision really was. He concluded, “How much more vision could anyone have at that time?”

So it’s not surprising that by 1985, Dr. Flanagan was the director of Bell Labs’ Information Principles Research Laboratory. And what a time to be the head of a well-funded research lab that had everything to do with communications, computers, and electronics!

Think of, say, your mobile phone. This device that fits into a pocket digitizes your voice, sends it by radio to a tower that’s probably some miles away, and it needs to be intelligible when it gets to the other end in almost real time. Flanagan’s work is at the core of that technology.

If that was the extent of his contributions, that would be pretty good, but there’s a lot more to Dr. Flanagan. Because remember his 1976 journal article: it wasn’t just about how to digitize voice, stuff it into the smallest bandwidth possible, and have it come out clear at the other end. It dealt with “Computers That Talk and Listen” — the basis of communications between humans and machines by voice.

And what do we have today? Computers that you can talk to, and get answers by a voice that sounds pretty human-like, not the mechanical staccato imagined by Star Trek for the 23rd century! Think Siri, the Google Assistant, Amazon’s Alexa, and others. You can turn to your phone and, without even touching it, say “OK Google: when did inventor James L. Flanagan die?”

August 25th, 2015. On the web site nap.edu*, they say James Loton Flanagan, an internationally recognized pioneer and a guiding force in digital voice processing, died August 25th, 2015, just four hours short of his 90th birthday.

*(NAP is the National Academies Press, an arm of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.)

Just like that. It was Flanagan who provided the vision and directed the team that made computer voices human-like — easy to understand. His vision not only led to that, but he established the basis for computers understanding our speech too: communication is a two-way street.

We generally speak in ways that other humans understand instantly, but computers have a hard time with. We know that, say, “the right to bear arms” refers to a guarantee made in the U.S. Constitution. But a computer? “The right” could mean the other direction from left. It could be about correctness or appropriateness. Or conforming with morality. Or the most favorable point in time, a position on the political spectrum, a 90-degree angle, a successful hit by a boxer, and much, much more.

All that is before we get to “bear,” which has multiple meanings, and “arms” — ditto. A computer has to sort through all of that and apply context that humans already know, because we don’t provide that context when we speak.

Simply put, computers are algorithmic, and humans definitely aren’t. And that’s before you factor in accents, slurring-words-together, and other impediments. It’s really, really hard stuff, but think about how well these devices understand what we’re saying! Yet we didn’t have it in Flanagan’s day because computers weren’t powerful enough to do it essentially immediately. They can now, even the tiny computer that’s the basis of a smartphone.

Still, Flanagan wasn’t done.

He was the lead or co-inventor on about 50 patents. Beyond Siri and other digital assistants, you can often talk to computers on the phone to get customer service from a bank. To get there, Flanagan and two others at Bell Labs developed adaptive differential pulse-code modulation, the building block technology behind digitizing speech. That led directly to digital sound storage used in voice mail systems, and then to VOIP, or the Voice Over Internet Protocol. Flanagan thought all of this work could also help in the music world, so he directed his researchers to work on that: the result was the MPEG-1 Layer 3 audio coding format, more commonly known as MP3, which led to digital music players. And then all of this was integrated into the smartphones of today.

Even though he devoted half of his work time to his own research, Flanagan also directed Bell Laboratories research in electroacoustics, psychoacoustics, array microphone processing, digital loudspeakers, robotics, and artificial intelligence: you can see how all of this fits together now that computer processing power has caught up with his vision from the 1970s.

Uncommon Sense? He had it in spades.

Happily, Dr. Flanagan was recognized for his innovations while he was still alive. He received the IEEE Achievement Award, the IEEE Centennial Medal, the 1986 IEEE Edison Medal for “a career of innovation and leadership in speech communication science and technology,” the Distinguished Service Award in Science from the American Speech and Hearing Association, and the IEEE Medal of Honor for “sustained leadership and outstanding contributions to speech technology.”

He worked at Bell Labs for 33 years, retiring as Bell Labs policy required, because he turned 65. (I never said AT&T’s bureaucrats had Uncommon Sense!) Not ready to retire back to the farm, he instead accepted a position as a professor — and vice president for research — at Rutgers University, passing on his Uncommon Sense to several generations of students until he finally really retired in 2005, after 15 years there.

The reality here in the 21st century far surpasses much of science fiction’s speculations in large part because of Jim Flanagan. His technological building blocks are behind what makes this podcast possible: it’s distributed in the MP3 format. It’s in just about all the music you play. It’s part of every phone call you make. “Every time we solved one challenge,” Rabiner said, “he was way ahead of us with the next challenge. He felt that his job was to produce a steady stream of out-of-the-box thinking.”

Yeah: that’s how you generate Uncommon Sense!

The Show Page for this episode is thisistrue.com/podcast61, which has a photo of Dr. Flanagan, and a place to comment.

I’m Randy Cassingham … and I’ll talk at you later.

– – –

Bad link? Broken image? Other problem on this page? Use the Help button lower right, and thanks.

This page is an example of my style of “Thought-Provoking Entertainment”. This is True is an email newsletter that uses “weird news” as a vehicle to explore the human condition in an entertaining way. If that sounds good, click here to open a subscribe form.

To really support This is True, you’re invited to sign up for a subscription to the much-expanded “Premium” edition:

Q: Why would I want to pay more than the minimum rate?

A: To support the publication to help it thrive and stay online: this kind of support means less future need for price increases (and smaller increases when they do happen), which enables more people to upgrade. This option was requested by existing Premium subscribers.

It shows what one person, with vision and the right tools, can do to change the world. None of this happens in a vacuum; he lead teams of people. You need passion at all levels. A good team with the right mix of people and the right resources will change the world.

Bell Labs had the right mix of vision, resources, and knowing how to hire and manage scientists and engineers. It was unique — there are very few companies that could replicate the environment.